Weird Tales, October 1931

Turlogh shouted and leaped forward.

Red welter of war and bloodshed—a vivid weird adventure

tale of the Orkney Islands when Canute the Dane ruled England.

LIGHTING dazzled the eyes of Turlogh O'Brien and his foot slipped in a smear of blood as he staggered on the reeling deck. The clashing of steel rivaled the bellowing of the thunder, and screams of death cut through the roar of waves and wind. The incessant lighting flicker gleamed on the corpses sprawling redly, the gigantic horned figures that roared and smote like huge demons of the midnight storm, the great beaked prow looming above.

The play was quick and desperate; in the momentary illumination a ferocious bearded face shone before Turlogh, and his swift ax licked out, splitting it to the chin. In the brief, utter blackness that followed the flash, an unseen stroke swept Turlogh's helmet from his head and he struck back blindly, feeling his ax sink into flesh, and hearing a man howl. Again the fires of the raging skies sprang, showing the Gael the ring of savage faces, the hedge of gleaming steel that hemmed him in.

Back against the mainmast Turlogh parried and smote; then through the madness of the fray a great voice thundered, and in a flashing instant the Gael caught a glimpse of a giant form—a strangely familiar face. Then the world crashed into fire-shot blackness.

Consciousness returned slowly. Turlogh was first aware of a swaying, rocking motion of his whole body which he could not check. Then a dull throbbing in his head racked him and he sought to raise his hands to it. Then it was he realized he was bound hand and foot—not an altogether new experience. Clearing sight showed him that he was tied to the mast of the dragon ship whose warriors had struck him down. Why they had spared him, he could not understand, because if they knew him at all, they knew him to be an outlaw—an outcast from his clan, who would pay no ransom to save him from the very pits of Hell.

The wind had fallen greatly but a heavy sea was flowing, which tossed the long ship like a chip from gulf-like trough to foaming crest. A round silver moon, peering through broken clouds, lighted the tossing billows. The Gael, raised on the wild west coast of Ireland, knew that the serpent ship was crippled. He could tell it by the way she labored, plowing deep into the spume, heeling to the lift of the surge. Well, the tempest which had been raging on these southern waters had been enough to damage even such staunch craft as these Vikings built.

The same gale had caught the French vessel on which Turlogh had been a passenger, driving her off her course and far southward. Days and nights had been a blind, howling chaos in which the ship had been hurled, flying like a wounded bird before the storm. And in the very rack of the tempest a beaked prow had loomed in the scud above the lower, broader craft, and the grappling irons had sunk in. Surely these Norsemen were wolves and the blood-lust that burned in their hearts was not human. In the terror and roar of the storm they leaped howling to the onslaught, and while the raging heavens hurled their full wrath upon them, and each shock of the frenzied waves threatened to engulf both vessels, these sea-wolves glutted their fury to the utmost—true sons of the sea, whose wildest rages found echo in their own bosoms. It had been a slaughter rather than a fight—the Celt had been the only fighting man aboard the doomed ship—and now he remembered the strange familiarity of the face he had glimpsed just before he was struck down. Who—?

"Good hail, my bold Dalcassian, it's long since we met!"

Turlogh stared at the man who stood before him, feet braced to the lifting of the deck. He was of huge stature, a good half head taller than Turlogh who stood well above six feet. His legs were like columns, his arms like oak and iron. His beard was of crisp gold, matching the massive armlets he wore. A shirt of scale-mail added to his war-like appearance as the horned helmet seemed to increase his height. But there was no wrath in the calm gray eyes which gazed tranquilly into the smoldering blue eyes of the Gael.

"Athelstane, the Saxon!"

"Aye—it's been a long day since you gave me this," the giant indicated a thin white scar on his temple. "We seem fated to meet on nights of fury—we first crossed steel the night you burned Thorfel's skalli. Then I fell before your ax and you saved me from Brogar's Picts—alone of all the folk who followed Thorfel. Tonight it was I who struck you down." He touched the great two-handed sword strapped to his shoulders and Turlogh cursed.

"Nay, revile me not," said Athelstane with a pained expression. "I could have slain you in the press—I struck with the flat, but knowing you Irish have cursed hard skulls, I struck with both hands. You have been senseless for hours. Lodbrog would have slain you with the rest of the merchant ship's crew but I claimed your life. But the Vikings would only agree to spare you on condition that you be bound to the mast. They know you of old."

"Where are we?"

"Ask me not. The storm blew us far out of our course. We were sailing to harry the coasts of Spain. When chance threw us in with your vessel, of course we seized the opportunity, but there was scant spoil. Now we are racing with the sea-flow, unknowing. The steer sweep is crippled and the whole ship lamed. We may be riding the very rim of the world for aught I know. Swear to join us and I will loose you."

"Swear to join the hosts of Hell!" snarled Turlogh. "Rather will I go down with the ship and sleep forever under the green waters, bound to this mast. My only regret is that I can not send more sea-wolves to join the hundred-odd I have already sent to purgatory!"

"Well, well," said Athelstane tolerantly, "a man must eat—here—I will loose your hands at least—now, set your teeth into this joint of meat."

Turlogh bent his head to the great joint and tore at it ravenously. The Saxon watched him a moment, then turned away. A strange man, reflected Turlogh, this renegade Saxon who hunted with the wolf-pack of the North—a savage warrior in battle, but with fibers of kindliness in his makeup which set him apart from the men with whom he consorted.

The ship reeled on blindly in the night, and Athelstane, returning with a great horn of foaming ale, remarked on the fact that the clouds were gathering again, obscuring the seething face of the sea. He left the Gael's hands unbound but Turlogh was held fast to the mast by cords about legs and body. The rovers paid no heed to their prisoner; they were too much occupied in keeping their crippled ship from going down under their feet.

At last Turlogh believed he could catch at times a deep roaring above the wash of the waves. This grew in volume, and even as the duller-eared Norsemen heard it, the ship leaped like a spurred horse, straining in every timber. As by magic the clouds, lightening for dawn, rolled away on each side, showing a wild waste of tossing gray waters, and a long line of breakers dead ahead. Beyond the frothing madness of the reefs loomed land, apparently an island. The roaring increased to deafening proportions, as the long ship, caught in the tide rip, raced headlong to her doom. Turlogh saw Lodbrog rushing about, his long beard flowing in the wind as he brandished his fists and bellowed futile commands. Athelstane came running across the deck.

"Little chance for any of us," he growled as he cut the Gael's bonds, "but you shall have as much as the rest—"

Turlogh sprang free. "Where is my ax?"

"There in that weapon-rack. But Thor's blood, man," marveled the big Saxon, "you won't burden yourself now—"

Turlogh had snatched the ax and confidence flowed like wine through his veins at the familiar feel of the slim, graceful shaft. His ax was as much a part of him as his right hand; if he must die he wished to die with it in his grip. He hastily slung it to his girdle. All armor had been stripped from him when he had been captured.

"There are sharks in these waters," said Athelstane, preparing to doff his scale-mail. "If we have to swim—"

The ship struck with a crash that snapped her masts and shivered her prow like glass. Her dragon beak shot high in the air and men tumbled like tenpins from her slanted deck. A moment she poised, shuddering like a live thing, then slid from the hidden reef and went down in a blinding smother of spray.

Turlogh had left the deck in a long dive that carried him clear. Now he rose in the turmoil, fought the waves for a mad moment, then caught a piece of wreckage that the breakers flung up. As he clambered across this, a shape bumped against him and went down again. Turlogh plunged his arm deep, caught a sword- belt and heaved the man up and on his makeshift raft. For in that instant he had recognized the Saxon, Athelstane, still burdened with the armor he had not had time to remove. The man seemed dazed. He lay limp, limbs trailing.

Turlogh remembered that ride through the breaker as a chaotic nightmare. The tide tore them through, plunging their frail craft into the depths, then flinging them into the skies. There was naught to do but hold on and trust to luck. And Turlogh held on, gripping the Saxon with one hand and their raft with the other, while it seemed his fingers would crack with the strain. Again and again they were almost swamped; then by some miracle they were through, riding in water comparatively calm and Turlogh saw a lean fin cutting the surface a yard away. It swirled in and Turlogh unslung his ax and struck. Red dyed the waters instantly and a rush of sinuous shapes made the craft rock. While the sharks tore their brother, Turlogh, paddling with his hands, urged the rude raft ashore until he could feel the bottom. He waded to the beach, half-carrying the Saxon; then, iron though he was, Turlogh O'Brien sank down, exhausted and soon slept soundly.

TURLOGH did not sleep long. When he awoke the sun was just risen above the sea-rim. The Gael rose, feeling as refreshed as if he had slept the whole night through, and looked about him. The broad white beach sloped gently from the water to a waving expanse of gigantic trees. There seemed no underbrush, but so close together were the huge boles, his sight could not pierce into the jungle. Athelstane was standing some distance away on a spit of sand that ran out into the sea. The huge Saxon leaned on his great sword and gazed out toward the reefs.

Here and there on the beach lay the stiff figures that had been washed ashore. A sudden snarl of satisfaction broke from Turlogh's lips. Here at his very feet was a gift from the gods; a dead Viking lay there, fully armed in the helmet and mail shirt he had not had time to doff when the ship foundered, and Turlogh saw they were his own. Even the round light buckler strapped to the Norseman's back was his. Turlogh did pause to wonder how all his accouterments had come into the possession of one man, but stripped the dead and donned the plain round helmet and the shirt of black chain mail. Thus armed he went up the beach toward Athelstane, his eyes gleaming unpleasantly.

The Saxon turned as he approached. "Hail to you Gael," he greeted. "We be all of Lodbrog's ship-people left alive. The hungry green sea drank them all. By Thor, I owe my life to you! What with the weight of mail, and the crack my skull got on the rail, I had most certainly been food for the shark but for you. It all seems like a dream now."

"You saved my life," snarled Turlogh. "I saved yours. Now the debt is paid, the accounts are squared, so up with your sword and let us make an end."

Athelstane stared. "You wish to fight me? Why—what—?"

"I hate your breed as I hate Satan!" roared the Gael, a tinge of madness in his blazing eyes. "Your wolves have ravaged my people for five hundred years! The smoking ruins of the Southland, the seas of spilled blood call for vengeance! The screams of a thousand ravished girls are ringing in my ears, night and day! Would that the North had but a single breast for my ax to cleave!"

"But I am no Norseman," rumbled the giant in worriment.

"The more shame to you, renegade," raved the maddened Gael. "Defend yourself lest I cut you down in cold blood!"

"This is not to my liking," protested Athelstane, lifting his mighty blade, his gray eyes serious but unafraid. "Men speak truly who say there is madness in you."

Words ceased as the men prepared to go into deadly action. The Gael approached his foe, crouching panther-like, eyes ablaze. The Saxon waited the onslaught, feet braced wide apart, sword held high in both hands. It was Turlogh's ax and shield against Athelstane's two-handed sword; in a contest one stroke might end either way. Like two great jungle beasts they played their deadly, wary game then—

Even as Turlogh's muscles tensed for the death-leap, a fearful sound split the silence! Both men started and recoiled. From the depths of the forest behind them rose a ghastly and inhuman scream. Shrill, yet of great volume, it rose higher and higher until it ceased at the highest pitch, like the triumph of a demon, like the cry of some grisly ogre gloating over its human prey.

"Thor's blood!" gasped the Saxon, letting his sword-point fall. "What was that?"

Turlogh shook his head. Even his iron nerve was slightly shaken. "Some fiend of the forest. This is a strange land in a strange sea. Mayhap Satan himself reigns here and it is the gate to Hell."

Athelstane looked uncertain. He was more pagan than Christian and his devils were heathen devils. But they were none the less grim for that.

"Well," said he, "let us drop our quarrel until we see what it may be. Two blades are better than one, whether for man or devil—"

A wild shriek cut him short. This time it was a human voice, blood-chilling in its horror and despair. Simultaneously came the swift patter of feet and the lumbering rush of some heavy body among the trees. The warriors wheeled toward the sound, and out of the deep shadows a half-naked woman came flying like a white leaf blown on the wind. Her loose hair streamed like a flame of gold behind her, her white limbs flashed in the morning sun, her eyes blazed with frenzied terror. And behind her—

Even Turlogh's hair stood up. The thing that pursued the fleeing girl was neither man nor beast. In form it was like a bird, but such a bird as the rest of the world had not seen for many an age. Some twelve feet high it towered, and its evil head with the wicked red eyes and cruel curved beak was as big as a horse's head. The long arched neck was thicker than a man's thigh and the huge taloned feet could have gripped the fleeing woman as an eagle grips a sparrow.

This much Turlogh saw in one glance as he sprang between the monster and its prey who sank down with a cry on the beach. It loomed above him like a mountain of death and the evil beak darted down, denting the shield he raised and staggering him with the impact. At the same instant he struck, but the keen ax sank harmlessly into a cushioning mass of spiky feathers. Again the beak flashed at him and his sidelong leap saved his life by a hair's breadth. And then Athelstane ran in, and bracing his feet wide, swung his great sword with both hands and all his strength. The mighty blade sheared through one of the tree-like legs below the knee, and with an abhorrent screech, the monster sank on its side, flapping its short heavy wings wildly. Turlogh drove the back-spike of his ax between the glaring red eyes and the gigantic bird kicked convulsively and lay still.

"Thor's blood!" Athelstane's gray eyes were blazing with battle lust. "Truly we've come to the rim of the world—"

"Watch the forest lest another come forth," snapped Turlogh, turning to the woman who had scrambled to her feet and stood panting, eyes wide with wonder. She was a splendid young animal, tall, clean-limbed, slim and shapely. Her only garment was a sheer bit of silk hung carelessly about her hips. But though the scantiness of her dress suggested the savage, her skin was snowy white, her loose hair of purest gold and her eyes gray. Now she spoke hastily, stammeringly, in the tongue of the Norse, as if she had not so spoken in years.

"You—who are you men? When come you? What do you on the Isle of the Gods?"

"Thor's blood!" rumbled the Saxon; "she's of our own kind!"

"Not mine!" snapped Turlogh, unable even in that moment to forget his hate for the people of the North.

The girl looked curiously at the two. "The world must have changed greatly since I left it," she said, evidently in full control of herself once more, "else how is it that wolf and wild bull hunt together? By your black hair, you are a Gael, and you, big man, have a slur in your speech that can be naught but Saxon."

"We are two outcasts," answered Turlogh. "You see these dead men lining the strand? They were the crew of the dragon ship which bore us here, storm-driven. This man, Athelstane, once of Wessex, was a swordsman on that ship and I was a captive. I am Turlogh Dubh, once a chief of Clan na O'Brien. Who are you and what land is this?"

"This is the oldest land in the world," answered the girl. "Rome, Egypt, Cathay are as but infants beside it. I am Brunhild, daughter of Rane Thorfin's son, of the Orkneys, and until a few days ago, queen of this ancient kingdom."

Turlogh looked uncertainly at Athelstane. This sounded like sorcery.

"After what we have just seen," rumbled the giant, "I am ready to believe anything. But are you in truth Rane Thorfin's son's stolen child?"

"Aye!" cried the girl, "I am that one! I was stolen when Tostig the Mad raided the Orkneys and burned Rane's steading in the absence of its master—"

"And then Tostig vanished from the face of the earth—or the sea!" interrupted Athelstane. "He was in truth a madman. I sailed with him for a ship-harrying many years ago when I was but a youth."

"And his madness cast me on this island," answered Brunhild; "for after he had harried the shores of England, the fire in his brain drove him out into unknown seas—south and south and ever south until even the fierce wolves he led murmured. Then a storm drove us on yonder reef, though at another part, rending the dragon ship even as yours was rended last night. Tostig and all his strong men perished in the waves, but I clung to pieces of wreckage and a whim of the gods cast me ashore, half-dead. I was fifteen years old. That was ten years ago.

"I found a strange terrible people dwelling here, a brown- skinned folk who knew many dark secrets of magic. They found me lying senseless on the beach and because I was the first white human they had ever seen, their priests divined that I was a goddess given them by the sea, whom they worship. So they put me in the temple with the rest of their curious gods and did reverence to me. And their high-priest, old Gothan—cursed be his name!— taught me many strange and fearful things. Soon I learned their language and much of their priests' inner mysteries. And as I grew into womanhood the desire for power stirred in me; for the people of the North are made to rule the folk of the world, and it is not for the daughter of a sea-king to sit meekly in a temple and accept the offerings of fruit and flowers and human sacrifices!"

She stopped for a moment, eyes blazing. Truly, she looked a worthy daughter of the fierce race she claimed.

"Well," she continued, "there was one who loved me—Kotar, a young chief. With him I plotted and at last I rose and flung off the yoke of old Gothan. That was a wild season of plot and counter-plot, intrigue, rebellion and red carnage! Men and women died like flies and the streets of Bal-Sagoth ran red—but in the end we triumphed, Kotar and I! The dynasty of Angar came to an end on a night of blood and fury and I reigned supreme on the Isle of the Gods, queen and goddess!"

She had drawn herself up to her full height, her beautiful face alight with fierce pride, her bosom heaving. Turlogh was at once fascinated and repelled. He had seen rulers rise and fall, and between the lines of her brief narrative he read the bloodshed and carnage, the cruelty and the treachery—sensing the basic ruthlessness of this girl- woman.

"But if you were queen," he asked, "how is it that we find you hunted through the forests of your domain by this monster, like a runaway serving wench?"

Brunhild bit her lip and an angry flush mounted to her cheeks. "What is it that brings down every woman, whatever her station? I trusted a man—Kotar, my lover, with whom I shared my rule. He betrayed me; after I had raised him to the highest power in the kingdom, next to my own, I found he secretly made love to another girl. I killed them both!"

Turlogh smiled coldly: "You are a true Brunhild! And then what?"

"Kotar was loved by the people. Old Gothan stirred them up. I made my greatest mistake when I let that old one live. Yet I dared not slay him. Well, Gothan rose against me, as I had risen against him, and the warriors rebelled, slaying those who stood faithful to me. Me they took captive but dared not kill; for after all, I was a goddess, they believed. So before dawn, fearing the people would change their minds again and restore me to power, Gothan had me taken to the lagoon which separates this part of the island from the other. The priests rowed me across the lagoon and left me, naked and helpless, to my fate."

"And that fate was—this?" Athelstane touched the huge carcass with his foot.

Brunhild shuddered. "Many ages ago there were many of these monsters on the isle, the legends say. They warred on the people of Bal-Sagoth and devoured them by hundreds. But at last all were exterminated on the main part of the isle and on this side of the lagoon all died but this one, who had abided here for centuries. In the old times hosts of men came against him, but he was greatest of all the devil-birds and he slew all who fought him. So the priests made a god of him and left this part of the island to him. None comes here except those brought as sacrifices—as I was. He could not cross to the main island, because the lagoon swarms with great sharks which would rend even him to pieces.

"For a while I eluded him, stealing among the trees, but at last he spied me out—and you know the rest. I owe my life to you. Now what will you do with me?"

Athelstane looked at Turlogh and Turlogh shrugged. "What can we do, save starve in this forest?"

"I will tell you!" the girl cried in a ringing voice, her eyes blazing anew to the swift working of her keen brain. "There is an old legend among this people—that men of iron will come out of the sea and the city of Bal-Sagoth will fall! You, with your mail and helmets, will seem as iron men to these folk who know nothing of armor! You have slain Groth-golka the bird- god—you have come out of the sea as did I—the people will look on you as gods. Come with me and aid me to win back my kingdom! You shall be my right-hand men and I will heap honors on you! Fine garments, gorgeous palaces, fairest girls shall be yours!"

Her promises slid from Turlogh's mind without leaving an imprint, but the mad splendor of the proposal intrigued him. Strongly he desired to look on this strange city of which Brunhild spoke, and the thought of two warriors and one girl pitted against a whole nation for a crown stirred the utmost depths of his knight-errant Celtic soul.

"It is well," said he. "And what of you, Athelstane?"

"My belly is empty," growled the giant. "Lead me to where there is food and I'll hew my way to it, through a horde of priests and warriors."

"Lead us to this city!" said Turlogh to Brunhild.

"Hail!" she cried flinging her white arms high in wild exultation. "Now let Gothan and Ska and Gelka tremble! With ye at my side I'll win back the crown they tore from me, and this time I'll not spare my enemy! I'll hurl old Gothan from the highest battlement, though the bellowing of his demons shake the very bowels of the earth! And we shall see if the god Gol-goroth shall stand against the sword that cut Groth-golka's leg from under him. Now hew the head from this carcass that the people may know you have overcome the bird-god. Now follow me, for the sun mounts the sky and I would sleep in my own palace tonight!"

The three passed into the shadows of the mighty forest. The interlocking branches, hundreds of feet above their heads, made dim and strange such sunlight as filtered through. No life was seen except for an occasional gayly hued bird or a huge ape. These beasts, Brunhild said, were survivors of another age, harmless except when attacked. Presently the growth changed somewhat, the trees thinned and became smaller and fruit of many kinds was seen among the branches. Brunhild told the warriors which to pluck and eat as they walked along. Turlogh was quite satisfied with the fruit, but Athelstane, though he ate enormously, did so with scant relish. Fruit was light sustenance to a man used to such solid stuff as formed his regular diet. Even among the gluttonous Danes the Saxon's capacity for beef and ale was admired.

"Look!" cried Brunhild sharply, halting and pointing. "The spires of Bal-Sagoth!"

Through the trees the warriors caught a glimmer: white and shimmery, and apparently far away. There was an illusory impression of towering battlements, high in the air, with fleecy clouds hovering about them. The sight woke strange dreams in the mystic deeps of the Gael's soul, and even Athelstane was silent as if he too were struck by the pagan beauty and mystery of the scene.

So they progressed through the forest, now losing sight of the distant city as treetops obstructed the view, now seeing it again. And at last they came out on the low shelving banks of a broad blue lagoon and the full beauty of the landscape burst upon their eyes. From the opposite shores the country sloped upward in long gentle undulations which broke like great slow waves at the foot of a range of blue hills a few miles away. These wide swells were covered with deep grass and many groves of trees, while miles away on either hand there was seen curving away into the distance the strip of thick forest which Brunhild said belted the whole island. And among those blue dreaming hills brooded the age-old city of Bal-Sagoth, its white walls and sapphire towers clean-cut against the morning sky. The suggestion of great distance had been an illusion.

"Is that not a kingdom worth fighting for?" cried Brunhild, her voice vibrant. "Swift now—let us bind this dry wood together for a raft. We could not live an instant swimming in that shark-haunted water."

At that instant a figure leaped up from the tall grass on the other shore—a naked, brown-skinned man who stared for a moment, agape. Then as Athelstane shouted and held up the grim head of Groth-golka, the fellow gave a startled cry and raced away like an antelope.

"A slave Gothan left to see if I tried to swim the lagoon," said Brunhild with angry satisfaction. "Let him run to the city and tell them—but let us make haste and cross the lagoon before Gothan can arrive and dispute our passage."

Turlogh and Athelstane were already busy. A number of dead trees lay about and these they stripped of their branches and bound together with long vines. In a short time they had built a raft, crude and clumsy, but capable of bearing them across the lagoon. Brunhild gave a frank sigh of relief when they stepped on the other shore.

"Let us go straight to the city," said she. "The slave has reached it ere now and they will be watching us from the walls. A bold course is our only one. Thor's hammer, but I'd like to see Gothan's face when the slave tells him Brunhild is returning with two strange warriors and the head of him to whom she was given as sacrifice!"

"Why did you not kill Gothan when you had the power?" asked Athelstane.

She shook her head, her eyes clouding with something akin to fear: "Easier said than done. Half the people hate Gothan, half love him, and all fear him. The most ancient men of the city say that he was old when they were babes. The people believe him to be more god than priest, and I myself have seen him do terrible and mysterious things, beyond the power of a common man.

"Nay, when I was but a puppet in his hands, I came only to the outer fringe of his mysteries, yet I have looked on sights that froze my blood. I have seen strange shadows flit along the midnight walls, and groping along black subterranean corridors in the dead of night I have heard unhallowed sounds and have felt the presence of hideous beings. And once I heard the grisly slavering bellowings of the nameless Thing Gothan has chained deep in the bowels of the hills on which rests the city of Bal- Sagoth."

Brunhild shuddered.

"There are many gods in Bal-Sagoth, but the greatest of all is Gol-goroth, the god of darkness who sits forever in the Temple of Shadows. When I overthrew the power of Gothan, I forbade men to worship Gol-goroth, and made the priest hail, as the one true deity, A-ala, the daughter of the sea—myself. I had strong men take heavy hammers and smite the image of Gol-goroth, but their blows only shattered the hammers and gave strange hurts to the men who wielded them. Gol-goroth was indestructible and showed no mar. So I desisted and shut the door of the Temple of Shadows which were opened only when I was overthrown and Gothan, who had been skulking in the secret places of the city, came again into his own. Then Gol-goroth reigned again in his full terror and the idols of A-ala were overthrown in the Temple of the Sea, and the priests of A-ala died howling on the red-stained altar before the black god. But now we shall see!"

"Surely you are a very Valkyrie," muttered Athelstane. "But three against a nation is great odds—especially such a people as this, who must assuredly be all witches and sorcerers."

"Bah!" cried Brunhild contemptuously. "There are many sorcerers, it is true, but though the people are strange to us, they are mere fools in their own way, as are all nations. When Gothan led me captive down the streets they spat on me. Now watch them turn on Ska, the new king Gothan has given them, when it seems my star rises again! But now we approach the city gates—be bold but wary!"

They had ascended the long swelling slopes and were not far from the walls which rose immensely upward. Surely, thought Turlogh, heathen gods built this city. The walls seemed of marble and with their fretted battlements and slim watch-towers, dwarfed the memory of such cities as Rome, Damascus, and Byzantium. A broad white winding road led up from the lower levels to the plateau before the gates and as they came up this road, the three adventurers felt hundreds of hidden eyes fixed on them with fierce intensity. The walls seemed deserted; it might have been a dead city. But the impact of those staring eyes was felt.

Now they stood before the massive gates, which to the amazed eyes of the warriors seemed to be of chased silver.

"Here is an emperor's ransom!" muttered Athelstane, eyes ablaze. "Thor's blood, if we had but a stout band of reavers and a ship to carry away the plunder!"

"Smite on the gate and then step back, lest something fall upon you," said Brunhild, and the thunder of Turlogh's ax on the portals woke the echoes in the sleeping hills.

The three then fell back a few paces and suddenly the mighty gates swung inward and a strange concourse of people stood revealed. The two white warriors looked on a pageant of barbaric grandeur. A throng of tall, slim, brown-skinned men stood in the gates. Their only garments were loincloths of silk, the fine work of which contrasted strangely with the near-nudity of the wearers. Tall waving plumes of many colors decked their heads, and armlets and leglets of gold and silver, crusted with gleaming gems, completed their ornamentation. Armor they wore none, but each carried a light shield on his left arm, made of hard wood, highly polished, and braced with silver. Their weapons were slim- bladed spears, light hatchets and slender daggers, all bladed with fine steel. Evidently these warriors depended more on speed and skill than on brute force.

At the front of this band stood three men who instantly commanded attention. One was a lean hawk-faced warrior, almost as tall as Athelstane, who wore about his neck a great golden chain from which was suspended a curious symbol in jade. One of the other men was young, evil-eyed; an impressive riot of colors in the mantle of parrot-feathers which swung from his shoulders. The third man had nothing to set him apart from the rest save his own strange personality. He wore no mantle, bore no weapons. His only garment was a plain loincloth. He was very old; he alone of all the throng was bearded, and his beard was as white as the long hair which fell about his shoulders. He was very tall and very lean, and his great dark eyes blazed as from a hidden fire. Turlogh knew without being told that this man was Gothan, priest of the Black God. The ancient exuded a very aura of age and mystery. His great eyes were like windows of some forgotten temple, behind which passed like ghosts his dark and terrible thoughts. Turlogh sensed that Gothan had delved too deep in forbidden secrets to remain altogether human. He had passed through doors that had cut him off from the dreams, desires and emotions of ordinary mortals. Looking into those unwinking orbs Turlogh felt his skin crawl, as if he had looked into the eyes of a great serpent.

Now a glance upward showed that the walls were thronged with silent dark-eyed folk. The stage was set; all was in readiness for the swift, red drama. Turlogh felt his pulse quicken with fierce exhilaration and Athelstane's eyes began to glow with ferocious light.

Brunhild stepped forward boldly, head high, her splendid figure vibrant. The white warriors naturally could not understand what passed between her and the others, except as they read from gestures and expressions, but later Brunhild narrated the conversation almost word for word.

"Well, people of Bal-Sagoth," said she, spacing her words slowly, "what words have you for your goddess whom you mocked and reviled?"

"What will you have, false one?" exclaimed the tall man, Ska, the king set up by Gothan. "You who mocked at the customs of our ancestors, defied the laws of Bal-Sagoth, which are older than the world, murdered your lover and defiled the shrine of Gol- goroth? You were doomed by law, king and god and placed in the grim forest beyond the lagoon—"

"And I, who am likewise a goddess and greater than any god," answered Brunhild mockingly, "am returned from the realm of horror with the head of Groth-golka!"

At a word from her, Athelstane held up the great beaked head, and a low whispering ran about the battlements, tense with fear and bewilderment.

"Who are these men?" Ska bent a worried frown on the two warriors.

"They are iron men who have come out of the sea!" answered Brunhild in a clear voice that carried far; "the beings who have come in response to the old prophesy, to overthrow the city of Bal-Sagoth, whose people are traitors and whose priests are false!"

At these words the fearful murmur broke out afresh all up and down the line of the walls, till Gothan lifted his vulture-head and the people fell silent and shrank before the icy stare of his terrible eyes.

Ska glared bewilderedly, his ambition struggling with his superstitious fears.

Turlogh, looking closely at Gothan, believed that he read beneath the inscrutable mask of the old priest's face. For all his inhuman wisdom, Gothan had his limitations. This sudden return of one he thought well disposed of, and the appearance of the white-skinned giants accompanying her, had caught Gothan off his guard, Turlogh believed, rightly. There had been no time to properly prepare for their reception. The people had already begun to murmur in the streets against the severity of Ska's brief rule. They had always believed in Brunhild's divinity; now that she returned with two tall men of her own hue, bearing the grim trophy that marked the conquest of another of their gods, the people were wavering. Any small thing might turn the tide either way.

"People of Bal-Sagoth!" shouted Brunhild suddenly, springing back and flinging her arms high, gazing full into the faces that looked down at her. "I bid you avert your doom before it is too late! You cast me out and spat on me; you turned to darker gods than I! Yet all this will I forgive if you return and do obeisance to me! Once you reviled me—you called me bloody and cruel! True, I was a hard mistress—but has Ska been an easy master? You said I lashed the people with whips of rawhide—has Ska stroked you with parrot feathers?

"A virgin died on my altar at the full tide of each moon—but youths and maidens die at the waxing and the waning, the rising and the setting of each moon, before Gol- goroth, on whose altar a fresh human heart forever throbs! Ska is but a shadow! Your real lord is Gothan, who sits above the city like a vulture! Once you were a mighty people; your galleys filled the seas. Now you are a remnant and that is dwindling fast! Fools! You will all die on the altar of Gol-goroth ere Gothan is done and he will stalk alone among the silent ruins of Bal-Sagoth!

"Look at him!" her voice rose to a scream as she lashed herself to an inspired frenzy, and even Turlogh, to whom the words were meaningless, shivered. "Look at him where he stands there like an evil spirit out of the past! He is not even human! I tell you, he is a foul ghost, whose beard is dabbled with the blood of a million butcheries—an incarnate fiend out of the mist of the ages come to destroy the people of Bal-Sagoth!

"Choose now! Rise up against the ancient devil and his blasphemous gods, receive your rightful queen and deity again and you shall regain some of your former greatness. Refuse, and the ancient prophesy shall be fulfilled and the sun will set on the silent and crumbled ruins of Bal-Sagoth!"

Fired by her dynamic words, a young warrior with the insignia of a chief sprang to the parapet and shouted: "Hail to A-ala! Down with the bloody gods!"

Among the multitude many took up the shout and steel clashed as a score of fights started. The crowd on the battlements and in the streets surged and eddied, while Ska glared, bewildered. Brunhild, forcing back her companions who quivered with eagerness for action of some kind, shouted: "Hold! Let no man strike a blow yet! People of Bal-Sagoth, it has been a tradition since the beginning of time that a king must fight for his crown! Let Ska cross steel with one of these warriors! If Ska wins, I will kneel before him and let him strike off my head! If Ska loses, then you shall accept me as your rightful queen and goddess!"

A great roar of approval went up from the walls as the people ceased their brawls, glad enough to shift the responsibility to their rulers.

"Will you fight, Ska?" asked Brunhild, turning to the king mockingly. "Or will you give me your head without further argument?"

"Slut!" howled Ska, driven to madness. "I will take the skulls of these fools for drinking cups, and then I will rend you between two bent trees!"

Gothan laid a hand on his arm and whispered in his ear, but Ska had reached the point where he was deaf to all but his fury. His achieved ambition, he had found, had faded to the mere part of a puppet dancing on Gothan's string; now even the hollow bauble of his kingship was slipping from him and this wench mocked him to his face before his people. Ska went, to all practical effects, stark mad.

Brunhild turned to her two allies. "One of you must fight Ska."

"Let me be the one!" urged Turlogh, eyes dancing with eager battle-lust. "He has the look of a man quick as a wildcat, and Athelstane, while a very bull for strength, is a thought slow for such work—"

"Slow!" broke in Athelstane reproachfully. "Why, Turlogh, for a man my weight—"

"Enough," Brunhild interrupted. "He must choose for himself."

She spoke to Ska, who glared red-eyed for an instant, then indicated Athelstane, who grinned joyfully, cast aside the bird's head and unslung his sword. Turlogh swore and stepped back. The king had decided that he would have a better chance against this huge buffalo of a man who looked slow, than against the black- haired tigerish warrior, whose cat-like quickness was evident.

"This Ska is without armor," rumbled the Saxon. "Let me likewise doff my mail and helmet so that we fight on equal terms—"

"No!" cried Brunhild. "Your armor is your only chance! I tell you, this false king fights like the play of summer lightning! You will be hard put to hold your own as it is. Keep on your armor, I say!"

"Well, well," grumbled Athelstane, "I will—I will. Though I say it is scarcely fair. But let him come on and make an end of it."

The huge Saxon strode ponderously toward his foe, who warily crouched and circled away. Athelstane held his great sword in both hands before him, pointed upward, the hilt somewhat below the level of his chin, in position to strike a blow to right or left, or to parry a sudden attack.

Ska had flung away his light shield, his fighting-sense telling him that it would be useless before the stroke of that heavy blade. In his right hand he held his slim spear as a man holds a throwing-dart, in his left a light, keen-edged hatchet. He meant to make a fast, shifty fight of it, and his tactics were good. But Ska, having never encountered armor before, made his fatal mistake in supposing it to be apparel or ornament through which his weapons would pierce.

Now he sprang in, thrusting at Athelstane's face with his spear. The Saxon parried with ease and instantly cut tremendously at Ska's legs. The king bounded high, clearing the whistling blade, and in midair he hacked down at Athelstane's bent head. The light hatchet shivered to bits on the Saxon's helmet and Ska sprang back out of reach with a blood-lusting howl.

And now it was Athelstane who rushed with unexpected quickness, like a charging bull, and before that terrible onslaught Ska, bewildered by the breaking of his hatchet, was caught off his guard—flat-footed. He caught a fleeting glimpse of the giant looming over him like an overwhelming wave and he sprang in, instead of out, stabbing ferociously. That mistake was his last. The thrusting spear glanced harmlessly from the Saxon's mail, and in that instant the great sword sang down in a stroke the king could not evade. The force of that stroke tossed him as a man is tossed by a plunging bull. A dozen feet away fell Ska, king of Bal-Sagoth, to lie shattered and dead in a ghastly welter of blood and entrails. The throng gaped, struck silent by the prowess of that deed.

"Hew off his head!" cried Brunhild, her eyes flaming as she clenched her hands so that the nails bit into her palms. "Impale that carrion's head on your sword-point so that we may carry it through the city gates with us as token of victory!"

But Athelstane shook his head, cleansing his blade: "Nay, he was a brave man and I will not mutilate his corpse. It is no great feat I have done, for he was naked and I full-armed. Else it is in my mind, the brawl had gone differently."

Turlogh glanced at the people on the walls. They had recovered from their astonishment and now a vast roar went up: "A-ala! Hail to the true goddess!" And the warriors in the gateway dropped to their knees and bowed their foreheads in the dust before Brunhild, who stood proudly erect, bosom heaving with fierce triumph. Truly, thought Turlogh, she is more than a queen—she is a shield woman, a Valkyrie, as Athelstane said.

Now she stepped aside and tearing the golden chain with its jade symbol from the dead neck of Ska, held it on high and shouted: "People of Bal-Sagoth, you have seen how your false king died before this golden-bearded giant, who being of iron, shows no single cut! Choose now—do you receive me of your own free will?"

"Aye, we do!" the multitude answered in a great shout. "Return to your people, oh mighty and all-powerful queen!"

Brunhild smiled sardonically. "Come," said she to the warriors; "they are lashing themselves into a very frenzy of love and loyalty, having already forgotten their treachery. The memory of the mob is short!"

Aye, thought Turlogh, as at Brunhild's side he and the Saxon passed through the mighty gates between files of prostrate chieftains; aye, the memory of the mob is very short. But a few days have passed since they were yelling as wildly for Ska the liberator—scant hours had passed since Ska sat enthroned, master of life and death, and the people bowed before his feet. Now—Turlogh glanced at the mangled corpse which lay deserted and forgotten before the silver gates. The shadow of a circling vulture fell across it. The clamor of the multitude filled Turlogh's ears and he smiled a bitter smile.

The great gates closed behind the three adventurers and Turlogh saw a broad white street stretching away in front of him. Other lesser streets radiated from this one. The two warriors caught a jumbled and chaotic impression of great white stone buildings shouldering each other; of sky-lifting towers and broad stair-fronted palaces. Turlogh knew there must be an ordered system by which the city was laid out, but to him all seemed a waste of stone and metal and polished wood, without rhyme or reason. His baffled eyes sought the street again.

Far up the street extended a mass of humanity, from which rose a rhythmic thunder of sound. Thousands of naked, gayly plumed men and women knelt there, bending forward to touch the marble flags with their foreheads, then swaying back with an upward flinging of their arms, all moving in perfect unison like the bending and rising of tall grass before the wind. And in time to their bowing they lifted a monotoned chant that sank and swelled in a frenzy of ecstasy. So her wayward people welcomed back the goddess A- ala.

Just within the gates Brunhild stopped and there came to her the young chief who had first raised the shout of revolt upon the walls. He knelt and kissed her bare feet, saying: "Oh great queen and goddess, thou knowest Zomar was ever faithful to thee! Thou knowest how I fought for thee and barely escaped the altar of Gol-goroth for thy sake!"

"Thou hast indeed been faithful, Zomar," answered Brunhild in the stilted language required for such occasions. "Nor shall thy fidelity go unrewarded. Henceforth thou art commander of my own bodyguard." Then in a lower voice she added: "Gather a band from your own retainers and from those who have espoused my cause all along, and bring them to the palace. I do not trust the people any more than I have to!"

Suddenly Athelstane, not understanding the conversation, broke in: "Where is the old one with the beard?"

Turlogh started and glanced around. He had almost forgotten the wizard. He had not seen him go—yet he was gone! Brunhild laughed ruefully.

"He's stolen away to breed more trouble in the shadows. He and Gelka vanished when Ska fell. He has secret ways of coming and going and none may stay him. Forget him for the time being; heed ye well—we shall have plenty of him anon!"

Now the chiefs brought a finely carved and highly ornamented palanquin carried by two strong slaves and Brunhild stepped into this, saying to her companions: "They are fearful of touching you, but ask if you would be carried. I think it better that you walk, one on each side of me."

"Thor's blood!" rumbled Athelstane, shouldering the huge sword he had never sheathed. "I'm no infant! I'll split the skull of the man who seeks to carry me!"

And so up the long white street went Brunhild, daughter of Rane Thorfin's son in the Orkneys, goddess of the sea, queen of age-old Bal-Sagoth. Borne by two great slaves she went, with a white giant striding on each side with bared steel, and a concourse of chiefs following, while the multitude gave way to right and left, leaving a wide lane down which she passed. Golden trumpets sounded a fanfare of triumph, drums thundered, chants of worship echoed to the ringing skies. Surely in this riot of glory, this barbaric pageant of splendor, the proud soul of the North-born girl drank deep and grew drunken with imperial pride.

Athelstane's eyes glowed with simple delight at this flame of pagan magnificence, but to the black haired fighting-man of the West, it seemed that even in the loudest clamor of triumph, the trumpet, the drum and shouting faded away into the forgotten dust and silence of eternity. Kingdoms and empires pass away like mist from the sea, thought Turlogh; the people shout and triumph and even in the revelry of Belshazzar's feast, the Medes break the gates of Babylon. Even now the shadow of doom is over this city and the slow tides of oblivion lap the feet of this unheeding race. So in a strange mood Turlogh O'Brien strode beside the palanquin, and it seemed to him that he and Athelstane walked in a dead city, through throngs of dim ghosts, cheering a ghost queen.

NIGHT had fallen on the ancient city of Bal- Sagoth. Turlogh, Athelstane and Brunhild sat alone in a room of the inner palace. The queen half-reclined on a silken couch, while the men sat on mahogany chairs, engaged in the viands that slave-girls had served on golden dishes. The walls of this room, as of all the palace, were of marble, with golden scrollwork. The ceiling was of lapis-lazuli and the floor of silver-inlaid marble tiles. Heavy velvet hangings decorated the walls and silken cushions; richly-made divans and mahogany chairs and tables littered the room in careless profusion.

"I would give much for a horn of ale, but this wine is not sour to the palate," said Athelstane, emptying a golden flagon with relish. "Brunhild, you have deceived us. You let us understand it would take hard fighting to win back your crown—yet I have struck but one blow and my sword is thirsty as Turlogh's ax which has not drunk at all. We hammered on the gates and the people fell down and worshipped with no more ado. And until a while ago, we but stood by your throne in the great palace room, while you spoke to the throngs that came and knocked their heads on the floor before you—by Thor, never have I heard such clattering and jabbering! My ears ring till now— what were they saying? And where is that old conjurer Gothan?"

"Your steel will drink deep yet, Saxon," answered the girl grimly, resting her chin on her hands and eyeing the warriors with deep moody eyes. "Had you gambled with cities and crowns as I have done, you would know that seizing a throne may be easier than keeping it. Our sudden appearance with the bird-god's head, your killing of Ska, swept the people off their feet. As for the rest—I held audience in the palace as you saw, even if you did not understand and the people who came in bowing droves were assuring me of their unswerving loyalty—ha! I graciously pardoned them all, but I am no fool. When they have time to think, they will begin to grumble again. Gothan is lurking in the shadows somewhere, plotting evil to us all, you may be sure. This city is honeycombed with secret corridors and subterranean passages of which only the priests know. Even I, who have traversed some of them when I was Gothan's puppet, know not where to look for the secret doors, since Gothan always led me through them blindfolded.

"Just now, I think I hold the upper hand. The people look on you with more awe than they regard me. They think your armor and helmets are part of your bodies and that you are invulnerable. Did you not note them timidly touching your mail as we passed through the crowd, and the amazement on their faces as they felt the iron of it?"

"For a people so wise in some ways they are very foolish in others," said Turlogh. "Who are they and whence came they?"

"They are so old," answered Brunhild, "that their most ancient legends give no hint of their origin. Ages ago they were a part of a great empire which spread out over the many isles of this sea. But some of the islands sank and vanished with their cities and people. Then the red-skinned savages assailed them and isle after isle fell before them. At last only this island was left unconquered, and the people have become weaker and forgotten many ancient arts. For lack of ports to sail to, the galleys rotted by the wharves which themselves crumbled into decay. Not in the memory of man has any son of Bal-Sagoth sailed the seas. At irregular intervals the red people descend upon the Isle of the Gods, traversing the seas in their long war-canoes which bear grinning skulls on the prows. Not far away as a Viking would reckon a sea-voyage, but out of sight over the sea rim lie the islands inhabited by those red men who centuries ago slaughtered the folk who dwelt there. We have always beaten them off; they can not scale the walls, but still they come and the fear of their raid is always hovering over the isle.

"But it is not them I fear; it is Gothan, who is at this moment either slipping like a loathly serpent through his black tunnels or else brewing abominations in one of his hidden chambers. In the caves deep in the hills to which his tunnels lead, he works fearful and unholy magic. His subjects are beasts—serpents, spiders, and great apes; and men—red captives and wretches of his own race. Deep in his grisly caverns he makes beasts of men and half-men of beasts, mingling bestial with human in ghastly creation. No man dares guess at the horrors that have spawned in the darkness, or what shapes of terror and blasphemy have come into being during the ages Gothan has wrought his abominations; for he is not as other men, and has discovered the secret of life everlasting. He has at least brought into foul life one creature that even he fears, the gibbering, mowing, nameless Thing he keeps chained in the farthest cavern that no human foot save his has trod. He would loose it against me if he dared...

"But it grows late and I would sleep. I will sleep in the room next to this, which has no other opening than this door. Not even a slave-girl will I keep with me, for I trust none of these people fully. You shall keep this room, and though the outer door is bolted, one had better watch while the other sleeps. Zomar and his guardsmen patrol the corridors outside, but I shall feel safer with two men of my own blood between me and the rest of the city."

She rose, and with a strangely lingering glance at Turlogh, entered her chamber and closed the door behind her.

Athelstane stretched and yawned. "Well, Turlogh," said he lazily, "men's fortunes are unstable as the sea. Last night I was the picked swordsman of a band of reavers and you a captive. This dawn we were lost outcasts springing at each other's throats. Now we are sword brothers and right-hand men to a queen. And you, I think, are destined to become a king."

"How so?"

"Why, have you not noticed the Orkney girl's eyes on you? Faith there's more than friendship in her glances that rest on those black locks and that brown face of yours. I tell you—"

"Enough," Turlogh's voice was harsh as an old wound stung him. "Women in power are white-fanged wolves. It was the spite of a woman that—" He stopped.

"Well, well," returned Athelstane tolerantly, "there are more good women than bad ones. I know—it was the intrigues of a woman that made you an outcast. Well, we should be good comrades. I am an outlaw, too. If I should show my face in Wessex I would soon be looking down on the countryside from a stout oak limb."

"What drove you out on the Viking path? So far have the Saxons forgotten the ocean-ways that King Alfred was obliged to hire Frisian rovers to build and man his fleet when he fought the Danes."

Athelstane shrugged his mighty shoulders and began whetting his dirk.

"I had a yearning for the sea even when I was a shock-headed child in Wessex. I was still a youth when I killed a young eorl and fled the vengeance of his people. I found refuge in the Orkneys and the ways of the Vikings were more to my liking than the ways of my own blood. But I came back to fight against Canute, and when England submitted to his rule he gave me command of his house-carles. That made the Danes jealous because of the honor given a Saxon who had fought against them, and the Saxons remembered I had left Wessex under a cloud once, and murmured that I was overly-well favored by the conquerors. Well, there was a Saxon thane and a Danish jarl who one night at feast assailed me with fiery words and I forgot myself and slew them both.

"So England—was—again—barred—to— me. I—took—the—Viking—path— again—"

Athelstane's words trailed off. His hands slid limply from his lap and the whetstone and dirk dropped to the floor. His head fell forward on his broad chest and his eyes closed.

"Too much wine," muttered Turlogh. "But let him slumber; I'll keep watch."

Yet even as he spoke, the Gael was aware of a strange lassitude stealing over him. He lay back in the broad chair. His eyes felt heavy and sleep veiled his brain despite himself. And as he lay there, a strange nightmare vision came to him. One of the heavy hangings on the wall opposite the door swayed violently and from behind it slunk a fearful shape that crept slavering across the room. Turlogh watched it apathetically, aware that he was dreaming and at the same time wondering at the strangeness of the dream. The thing was grotesquely like a crooked gnarled man in shape, but its face was bestial. It bared yellow fangs as it lurched silently toward him, and from under penthouse brows small reddened eyes gleamed demoniacally. Yet there was something of the human in its countenance; it was neither ape nor man, but an unnatural creature horribly compounded of both.

Now the foul apparition halted before him, and as the gnarled fingers clutched his throat, Turlogh was suddenly and fearfully aware that this was no dream but a fiendish reality. With a burst of desperate effort he broke the unseen chains that held him and hurled himself from the chair. The grasping fingers missed his throat, but quick as he was, he could not elude the swift lunge of those hairy arms, and the next moment he was tumbling about the floor in a death grip with the monster, whose sinews felt like pliant steel.

That fearful battle was fought in silence save for the hissing of hard-drawn breath. Turlogh's left forearm was thrust under the apish chin, holding back the grisly fangs from his throat, about which the monster's fingers had locked. Athelstane still slept in his chair, head fallen forward. Turlogh tried to call to him, but those throttling hands had shut off his voice—were fast choking out his life. The room swam in a red haze before his distended eyes. His right hand, clenched into an iron mallet, battered desperately at the fearful face bent toward his; the beast-like teeth shattered under his blows and blood splattered, but still the red eyes gloated and the taloned fingers sank deeper and deeper until a ringing in Turlogh's ears knelled his soul's departure.

Even as he sank into semi-unconsciousness, his falling hand struck something his numbed fighting-brain recognized as the dirk Athelstane had dropped on the floor. Blindly, with a dying gesture, Turlogh struck and felt the fingers loosen suddenly. Feeling the return of life and power, he heaved up and over, with his assailant beneath him. Through red mists that slowly lightened, Turlogh Dubh saw the ape-man, now encrimsoned, writhing beneath him, and he drove the dirk home until the dumb horror lay still with wide staring eyes.

The Gael staggered to his feet, dizzy and panting, trembling in every limb. He drew in great gulps of air and his giddiness slowly cleared. Blood trickled plentifully from the wounds in his throat. He noted with amazement that the Saxon still slumbered. And suddenly he began to feel again the tides of unnatural weariness and lassitude that had rendered him helpless before. Picking up his ax, he shook off the feeling with difficulty and stepped toward the curtain from behind which the ape-man had come. Like an invisible wave a subtle power emanating from those hangings struck him, and with weighted limbs he forced his way across the room. Now he stood before the curtain and felt the power of a terrific evil will beating upon his own, menacing his very soul, threatening to enslave him, brain and body. Twice he raised his hand and twice it dropped limply to his side. Now for the third time he made a mighty effort and tore the hangings bodily from the wall. For a flashing instant he caught a glimpse of a bizarre, half-naked figure in a mantle of parrot-feathers and a head-gear of waving plumes. Then as he felt the full hypnotic blast of those blazing eyes, he closed his own eyes and struck blind. He felt his ax sink deep; then he opened his eyes and gazed at the silent figure which lay at his feet, cleft head in a widening crimson pool.

And now Athelstane suddenly heaved erect, eyes flaring bewilderedly, sword out. "What—?" he stammered, glaring wildly. "Turlogh, what in Thor's name's happened? Thor's blood! That is a priest there, but what is this dead thing?"

"One of the devils of this foul city," answered Turlogh, wrenching his ax free. "I think Gothan has failed again. This one stood behind the hangings and bewitched us unawares. He put the spell of sleep on us—"

"Aye, I slept," the Saxon nodded dazedly. "But how came they here—"

"There must be a secret door behind those hangings, though I can not find it—"

"Hark!" From the room where the queen slept there came a vague scuffling sound, that in its very faintness seemed fraught with grisly potentialities.

"Brunhild!" Turlogh shouted. A strange gurgle answered him. He thrust against the door. It was locked. As he heaved up his ax to hew it open, Athelstane brushed him aside and hurled his full weight against it. The panels crashed and through their ruins Athelstane plunged into the room. A roar burst from his lips. Over the Saxon's shoulder Turlogh saw a vision of delirium. Brunhild, queen of Bal-Sagoth, writhed helpless in midair, gripped by the black shadow of a nightmare. Then as the great black shape turned cold flaming eyes on them Turlogh saw it was a living creature. It stood, man-like, upon two tree-like legs, but its outline and face were not of a man, beast or devil. This, Turlogh felt, was the horror that even Gothan had hesitated to loose upon his foes; the arch-fiend that the demoniac priest had brought into life in his hidden caves of horror. What ghastly knowledge had been necessary, what hideous blending of human and bestial things with nameless shapes from outer voids of darkness?

Held like a babe in arms Brunhild writhed, eyes flaring with horror, and as the Thing took a misshapen hand from her white throat to defend itself, a scream of heart-shaking fright burst from her pale lips. Athelstane, first in the room, was ahead of the Gael. The black shape loomed over the giant Saxon, dwarfing and overshadowing him, but Athelstane, gripping the hilt with both hands, lunged upward. The great sword sank over half its length into the black body and came out crimson as the monster reeled back. A hellish pandemonium of sound burst forth, and the echoes of that hideous yell thundered through the palace and deafened the hearers. Turlogh was springing in, ax high, when the fiend dropped the girl and fled reeling across the room, vanishing in a dark opening that now gaped in the wall. Athelstane, clean berserk, plunged after it.

Turlogh made to follow, but Brunhild, reeling up, threw her white arms around him in a grip even he could hardly break. "No!" she screamed, eyes ablaze with terror. "Do not follow them into that fearful corridor! It must lead to Hell itself! The Saxon will never return! Let you not share his fate!"

"Loose me, woman!" roared Turlogh in a frenzy, striving to disengage himself without hurting her. "My comrade may be fighting for his life!"

"Wait till I summon the guard!" she cried, but Turlogh flung her from him, and as he sprang through the secret doorway, Brunhild smote on the jade gong until the palace re-echoed. A loud pounding began in the corridor and Zomar's voice shouted: "Oh, queen, are you in peril? Shall we burst the door?"

"Hasten!" she screamed, as she rushed to the outer door and flung it open.

Turlogh, leaping recklessly into the corridor, raced along in darkness for a few moments, hearing ahead of him the agonized bellowing of the wounded monster and the deep fierce shouts of the Saxon. Then these noises faded away in the distance as he came into the narrow passageway faintly lighted with torches stuck into niches. Face down on the floor lay a brown man, clad in gray feathers, his skull crushed like an eggshell.

How long Turlogh O'Brien followed the dizzy windings of the shadowy corridor he never knew. Other smaller passages led off to each side but he kept to the main corridor. At last he passed under an arched doorway and came out into a strange vasty room.

Somber massive columns upheld a shadowy ceiling so high it seemed like a brooding cloud arched against a midnight sky. Turlogh saw that he was in a temple. Behind a black red-stained stone altar loomed a mighty form, sinister and abhorrent. The god Gol-goroth! Surely it must be he. But Turlogh spared only a single glance for the colossal figure that brooded there in the shadows. Before him was a strange tableau. Athelstane leaned on his great sword and gazed at the two shapes which sprawled in a red welter at his feet. Whatever foul magic had brought the Black Thing into life, it had taken but a thrust of English steel to hurl it back into a limbo from whence it came. The monster lay half-across its last victim—a gaunt white-bearded man whose eyes were starkly evil, even in death.

"Gothan!" ejaculated the startled Gael.

"Aye, the priest—I was close behind this troll or whatever it is, all the way along the corridor, but for all its size it fled like a deer. Once one in a feather mantle tried to halt it, and it smashed his skull and paused not an instant. At last we burst into this temple, I closed upon the monster's heels with my sword raised for the death-cut. But Thor's blood! When it saw the old one standing by that altar, it gave one fearful howl and tore him to pieces and died itself, all in an instant, before I could reach it and strike."

Turlogh gazed at the huge formless thing. Looking directly at it, he could form no estimate of its nature. He got only a chaotic impression of great size and inhuman evil. Now it lay like a vast shadow blotched out on the marble floor. Surely black wings beating from moonless gulfs had hovered over its birth, and the grisly souls of nameless demons had gone into its being.

And now Brunhild rushed from the dark corridor with Zomar and the guardsmen. And from outer doors and secret nooks came others silently—warriors, and priests in feathered mantles, until a great throng stood in the Temple of Darkness.

A fierce cry broke from the queen as she saw what had happened. Her eyes blazed terribly and she was gripped by a strange madness.

"At last!" she screamed, spurning the corpse of her arch-foe with her heel. "At last I am true mistress of Bal-Sagoth! The secrets of the hidden ways are mine now, and old Gothan's beard is dabbled in his own blood!"

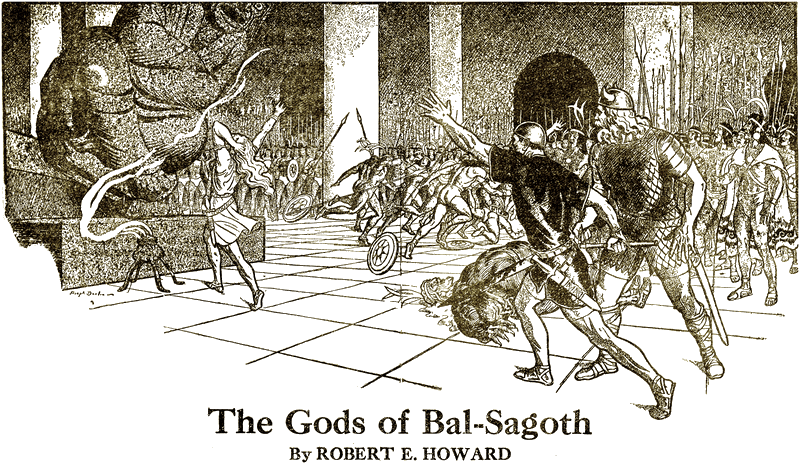

She flung her arms high in fearful triumph, and ran toward the grim idol, screaming exultant insults like a mad-woman. And at that instant the temple rocked! The colossal image swayed outward, and then pitched suddenly forward as a tall tower falls. Turlogh shouted and leaped forward, but even as he did, with a thunder like the bursting of a world, the god Gol-goroth crashed down upon the doomed woman, who stood frozen. The mighty image splintered into a thousand great fragments, blotting from the sight of men forever Brunhild, daughter of Rane Thorfin's son, queen of Bal-Sagoth. From under the ruins there oozed a wide crimson stream.

Warriors and priests stood frozen, deafened by the crash of that fall, stunned by the weird catastrophe. An icy hand touched Turlogh's spine. Had that vast bulk been thrust over by the hand of a dead man? As it had rushed downward it had seemed to the Gael that the inhuman features had for an instant taken on the likeness of the dead Gothan!

Now as all stood speechless, the acolyte Gelka saw and seized his opportunity.

"Gol-goroth has spoken!" he screamed. "He has crushed the false goddess! She was but a wicked mortal! And these strangers, too, are mortal! See—he bleeds!"

The priest's finger stabbed at the dried blood on Turlogh's throat and a wild roar went up from the throng. Dazed and bewildered by the swiftness and magnitude of the late events, they were like crazed wolves, ready to wipe out doubts and fear in a burst of bloodshed. Gelka bounded at Turlogh, hatchet flashing, and a knife in the hand of a satellite licked into Zomar's back. Turlogh had not understood the shout, but he realized the air was tense with danger for Athelstane and himself. He met the leaping Gelka with a stroke that sheared through the waving plumes and the skull beneath, then half a dozen lances broke on his buckler and a rush of bodies swept him back against a great pillar. Then Athelstane, slow of thought, who had stood gaping for the flashing second it had taken this to transpire, awoke in a blast of awesome fury. With a deafening roar he swung his heavy sword in a mighty arc. The whistling blade whipped off a head, sheared through a torso and sank deep into a spinal column. The three corpses fell across each other and even in the madness of the strife, men cried out at the marvel of that single stroke.

But like a brown, blind tide of fury the maddened people of Bal-Sagoth rolled on their foes. The guardsmen of the dead queen, trapped in the press, died to a man without a chance to strike a blow. But the overthrow of the two white warriors was no such easy task. Back to back they smashed and smote; Athelstane's sword was a thunderbolt of death; Turlogh's ax was lightning. Hedged close by a sea of snarling brown faces and flashing steel they hacked their way slowly toward a doorway. The very mass of the attackers hindered the warriors of Bal-Sagoth, for they had no space to guide their strokes, while the weapons of the seafarers kept a bloody ring clear in front of them.

Heaping a ghastly row of corpses as they went, the comrades slowly cut their way through the snarling press. The Temple of Shadows, witness of many a bloody deed, was flooded with gore spilled like a red sacrifice to her broken gods. The heavy weapons of the white fighters wrought fearful havoc among their naked, lighter-limbed foes, while their armor guarded their own lives. But their arms, legs and faces were cut and gashed by the frantically flying steel and it seemed the sheer number of their foes would overwhelm them ere they could reach the door.

Then they had reached it, and made desperate play until the brown warriors, no longer able to come upon them from all sides, drew back for a breathing-space, leaving a torn red heap before the threshold. And in that instant the two sprang back into the corridor and seizing the great brazen door, slammed it in the very faces of the warriors who leaped howling to prevent it. Athelstane, bracing his mighty legs, held it against their combined efforts until Turlogh had time to find and slip the bolt.

"Thor!" gasped the Saxon, shaking the blood in a red shower from his face. "This is close play! What now, Turlogh?"

"Down the corridor, quick!" snapped the Gael, "before they come on us from this way and trap us like rats against this door. By Satan, the whole city must be roused! Hark to that roaring!"

In truth, as they raced down the shadowed corridor, it seemed to them that all Bal-Sagoth had burst into rebellion and civil war. From all sides came the clashing of steel, the shouts of men, and the screams of women, overshadowed by a hideous howling. A lurid glow became apparent down the corridor and then even as Turlogh, in the lead, rounded a corner and came out into an open courtyard, a vague figure leaped at him and a heavy weapon fell with unexpected force on his shield, almost felling him. But even as he staggered he struck back and the upper-spike on his ax sank under the heart of his attacker, who fell at his feet. In the glare that illumined all, Turlogh saw his victim differed from the brown warriors he had been fighting. This man was naked, powerfully muscled and of a copperish red rather than brown. The heavy animal-like jaw, the slanting low forehead showed none of the intelligence and refinement of the brown people, but only a brute ferocity. A heavy war-club, rudely carved, lay beside him.

"By Thor!" exclaimed Athelstane. "The city burns!"

Turlogh looked up. They were standing on a sort of raised courtyard from which broad steps led down into the streets and from this vantage point they had a plain view of the terrific end of Bal-Sagoth. Flames leaped madly higher and higher, paling the moon, and in the red glare pigmy figures ran to and fro, falling and dying like puppets dancing to the tune of the Black Gods. Through the roar of the flames and the crashing of falling walls cut screams of death and shrieks of ghastly triumph. The city was swarming with naked, copper-skinned devils who burned and ravished and butchered in one red carnival of madness.

The red men of the isles! By the thousands they had descended on the Isle of the Gods in the night, and whether stealth or treachery let them through the walls, the comrades never knew, but now they ravened through the corpse-strewn streets, glutting their blood-lust in holocaust and massacre wholesale. Not all the gashed forms that lay in the crimson-running streets were brown; the people of the doomed city fought with desperate courage, but outnumbered and caught off guard, their courage was futile. The red men were like blood-hungry tigers.

"What ho, Turlogh!" shouted Athelstane, beard a-bristle, eyes ablaze as the madness of the scene fired a like passion in his own fierce soul. "The world ends! Let us into the thick of it and glut our steel before we die! Who shall we strike for—the red or the brown?"

"Steady!" snapped the Gael. "Either people would cut our throats. We must hack our way through to the gates, and the Devil take them all. We have no friends here. This way—down these stairs. Across the roofs in yonder direction I see the arch of a gate."

The comrades sprang down the stairs, gained the narrow street below and ran swiftly in the way Turlogh indicated. About them washed a red inundation of slaughter. A thick smoke veiled all now, and in the murk chaotic groups merged, writhed and scattered, littering the shattered flags with gory shapes. It was like a nightmare in which demoniac figures leaped and capered, looming suddenly in the fire-shot mist, vanishing as suddenly. The flames from each side of the streets shouldered each other, singeing the hair of the warriors as they ran. Roofs fell in with an awesome thunder and walls crashing into ruin filled the air with flying death. Men struck blindly from the smoke and the seafarers cut them down and never knew whether their skins were brown or red.

Now a new note rose in the cataclysmic horror. Blinded by the smoke, confused by the winding streets, the red men were trapped in the snare of their own making. Fire is impartial; it can burn the lighter as well as the intended victim; and a falling wall is blind. The red men abandoned their prey and ran howling to and fro like beasts, seeking escape; many, finding this futile, turned back in a last unreasoning storm of madness as a blinded tiger turns, and made their last moments of life a crimson burst of slaughter.

Turlogh, with the unerring sense of direction that comes to men who live the life of the wolf, ran toward the point where he knew an outer gate to be; yet in the windings of the streets and the screen of smoke, doubt assailed him. From the flame-shot murk in front of him a fearful scream rang out. A naked girl reeled blindly into view and fell at Turlogh's feet, blood gushing from her mutilated breast. A howling, red-stained devil, close on her heels, jerked back her head and cut her throat, a fraction of a second before Turlogh's ax ripped the head from its shoulders and spun it grinning into the street. And at that second a sudden wind shifted the writhing smoke and the comrades saw the open gateway ahead of them, a-swarm with red warriors. A fierce shout, a blasting rush, a mad instant of volcanic ferocity that littered the gateway with corpses, and they were through and racing down the slopes toward the distant forest and the beach beyond. Before them the sky was reddening for dawn; behind them rose the soul- shaking tumult of the doomed city.

Like hunted things they fled, seeking brief shelter among the many groves from time to time, to avoid groups of savages who ran toward the city. The whole island seemed to be swarming with them; the chiefs must have drawn on all the isles within hundreds of miles for a raid of such magnitude. And at last the comrades reached the strip of forest, and breathed deeply as they came to the beach and found it abandoned save for a number of long skull- decorated war canoes.

Athelstane sat down and gasped for breath. "Thor's blood! What now? What may we do but hide in these woods until those red devils hunt us out?"

"Help me launch this boat," snapped Turlogh. We'll take our chance on the open main—"

"Ho!" Athelstane leaped erect, pointing. "Thor's blood, a ship!"

The sun was just up, gleaming like a great golden coin on the sea-rim. And limned in the sun swam a tall, high-pooped craft. The comrades leaped into the nearest canoe, shoved off and rowed like mad, shouting and waving their oars to attract the attention of the crew. Powerful muscles drove the long slim craft along at an incredible clip, and it was not long before the ship stood about and allowed them to come alongside. Dark-faced men, clad in mail, looked over the rail.

"Spaniards," muttered Athelstane. "If they recognize me, I had better stayed on the island!"

But he clambered up the chain without hesitation, and the two wanderers fronted the lean somber-faced man whose armor was that of a knight of Asturias. He spoke to them in Spanish and Turlogh answered him, for the Gael, like many of his race, was a natural linguist and had wandered far and spoken many tongues. In a few words the Dalcassian told their story and explained the great pillar of smoke which now rolled upward in the morning air from the isle.