RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

"Flying to Fortune," George Newnes Ltd., London, 1933

Title page of "Flying to Fortune"

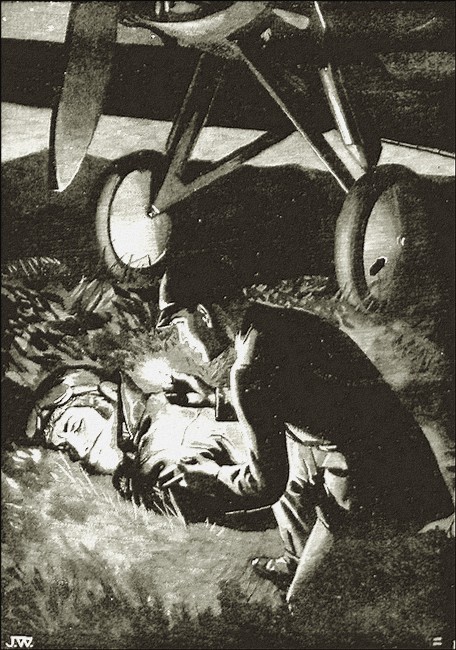

The light showed him a man lying on his face,

with his hands and ankles firmly lashed.

FISHING-ROD in hand, creel on back, Jock Freeland ran down the heather-clad slope of Pixies Tor towards the road. It was later than he had thought, and he knew just exactly what Great Aunt Sarah would say and how she would look if he was even one minute late for supper. The way her lips would pinch together and the cold glare of disapproval from behind her gold-rimmed glasses.

"I don't believe she ever was young," Jock said to himself, and just then he heard the deep hum of an engine and pulled up short to see a car coming up the valley road.

Nothing much in that, you will say, yet it was odd, for cars did not use this road, especially big cars, and this was a very big one and held four men and a tremendous pile of luggage. Queer-looking luggage, for it consisted of great boxes and long wooden cases covered with sacking. Opposite Jock the car pulled up.

"Hi, boy!" cried the driver in a big, deep voice. "Can you get to Taverton this way?" Jock came forward.

"You can, but it's a rotten road. Bad surface and awful hills." The driver laughed. He was big like his voice. He must weigh fifteen stone, Jock thought, yet his weight was mostly muscle. He had bright red hair and bright blue eyes, and gave Jock a feeling of tremendous power and force.

"I don't mind the hills," he said. "This old bus'll climb anything, and I reckon our tyres are good. How does the road run?"

"Right over the top of the Moor," Jock answered. The big man opened out a map.

"Is this it?" he asked, pointing with a huge forefinger.

"Yes, it passes the old Lar Tor tin mine."

"There's a track marked from the mine to the main road. Could I take the car down that?"

"You might," said Jock doubtfully. "But it's just a cart track, and hasn't been used for years." The big fellow turned to a dark-faced man sitting next him.

"Guess we'll try it, Tony."

"Just as you say, Red," replied Tony. Red spoke again to Jock.

"Thank you, son. We're bound for the fair at Taverton. Maybe we'll see you there to-morrow." Jock shook his head.

"Not likely, I'm afraid," he said briefly.

"Well, so long," said Red genially as he pushed in first gear and started up.

"Rum-looking outfit," said Jock to himself as he watched the big car boom away up the hill. Then he started running again and Just managed to reach Foxen Holt in time for supper.

It was a deadly meal. Once she had satisfied herself that Jock's hands were clean and his hair brushed, Aunt Sarah seldom troubled to make conversation. Jock was only too glad when it was over and he could escape. He decided to start his weekly letter to his father, who was an air-pilot in Mesopotamia, and went up to his rooms to do so.

It was growing dark and the night was still and very warm. A pleasant scent of heather came through the open window, and a curlew was calling mournfully as it winged through the late dusk.

"Dear Dad," Jock began, and paused for inspiration. Suddenly a beam of light shot up into the sky from the other side of Lar Tor, and Jock dropped his pen and stared in amazement.

"A searchlight in the middle of the Moor!" he exclaimed. "What on earth are they playing at?" The beam quivered, then steadied. It seemed to shorten, yet he could still see its glow. Up he jumped and slipped cautiously downstairs. Aunt Sarah was in the drawing-room, the door shut as usual, and he could hear Hannah rattling dishes in the kitchen.

The coast was clear, so snatching up his cap he let himself cautiously out of the front door, and next minute had passed through the wicket-gate at the end of the garden and was breasting the steep hill.

Lar Tor rises to fourteen hundred feet, and Jock was hot and breathless when he reached the top of the great ridge. Now he could see the light quite plainly. It came from a point near the old tin mine, a mile from where he was standing, and he saw that there was not one light but several.

"Landing lights," he said to himself, for as the son of an airman Jock was wise about this sort of thing. He had done a lot of flying with his father. "They must be expecting a plane."

He paused and tried to remember just how the land lay. "Yes," he went on, "there's quite a level patch and I suppose a plane could land there. But it would be beastly risky. And who on earth would want to land in the middle of the moor?" Then a new idea flashed through his mind. Smugglers! He knew that a deal of smuggling is done nowadays by air. He tingled with excitement. "I'm jolly well going to see what's up," he vowed as he hurried on.

He had covered about half the distance when he heard the unmistakable drone of a plane. It was far too dark to see her, but the sound told him she was coming from the north. Another minute and the drone ceased. The pilot had cut out his engine and was planing down. Then Jock saw the plane dropping into the lighted area. He saw it land, and next instant the lights went out.

Jock began to run, but the ground was treacherous, all covered with boulders and thick heather, and twice he took bad tumbles. It was a good five minutes before he reached the level ground. Now he had to go quietly if he did not want to be seen, so down he went on hands and knees, creeping silently through the heather.

By this time it was quite dark, but though there was no moon the stars gave light enough for him to spot the outline of a good-sized plane standing in the open. He stopped and listened and distinctly heard a car moving away down the old cart track towards the main road.

He stood up and saw its lights. It was bumping and jolting along on low gear. It appeared to be a big car, and Jock's thoughts flashed hack to the one he had seen two hours earlier on the valley road.

"Something fishy about this," he muttered. "Anyhow, I'm going to have a look at that plane." He went slowly forward and had nearly reached the plane when he stumbled over something lying flat in the heather. It was the body of a man.

JOCK'S heart seemed to turn over; he felt as if icy fingers were being drawn down his spine. Though he was boiling hot he shivered. Then the body moved and made a grunting sound, and Jock realized with the deepest gratitude that the man was still alive.

He found his matchbox, and with fingers not quite steady struck one. The light showed him a man lying on his face, with his hands and ankles firmly lashed. He was gagged with a piece of cloth. The man wore a leather jacket and helmet, and Jock knew at once that he was the pilot of the plane. Out came his knife, and the sharp blade made short work of the cords. Then he cut away the gag.

The man sat up with a jerk. He was a tall, slim fellow, and even in the dim light Jock could see that he was quite young.

"Who are you?" he demanded hoarsely—"one of them?"

"I'm Jock Freeland. I saw the landing lights. That's why I came." The other struggled to his feet.

"Landing lights. Yes, I thought I was over Okestock. They were on me like a shot the moment I got down. They got my stuff and are off with it," he added savagely. He gazed round, but by this time the car was out of sight. "Did you see them, Freeland?" he asked sharply.

"I saw a car," Jock told him. "It was going down the cart track towards the main road."

"A car," the other was all eagerness. "I thought they had a plane, but if it's a car there's still a chance. That is, if they haven't busted my plane." He sprang towards the plane, switched on a flash light and examined it swiftly.

"It's all right," he said sharply. "By gum, I'll go after them." He pulled over the prop, and the engine, still hot, started at once. Then he looked at Jock.

"Will you come with me. You'd he able to spot the car. Or would you funk it?"

"Funk it!" retorted Jock. "What's there to funk? Think I've never been up before? My dad's a pilot?"

"Freeland, you said your name was. You're not Ronald Freeland's boy?"

"I am," said Jock as he scrambled into the plane.

"Gosh, I'm in luck," cried the other as he followed. "My name's Hanley—Finch Hanley. Your dad taught me to fly. Put on that spare helmet. We can talk as we go." Jock slipped on the helmet and plugged in the phones.

"Can you get her up?" he asked. "You'll have to look out for rocks."

"I came down all right. I'd better turn her and get the same run. Luckily I have lights." He switched them on, then turned the plane and taxied back. Then he turned her again and opened the throttle. She went up like a bird, and as soon as she was off the ground Hanley switched off the lights.

"Where are we?" he asked Jock.

"Almost the middle of the Moor. Okestock's due north."

"Which way will the car go?"

"They'll strike the main road in less than a mile. If you go west you reach Taverton, the other way you can go to Plymouth ox Exeter."

"Plymouth's their line, I'll lay. The odds are they have a motor-boat ready and they'll make for Holland. That's the market for stones."

"Jewels, you mean?"

"Jewels. Gosh, didn't I tell you? They've got the Meripit Emeralds. Worth fifty thousand quid." Jock gasped. Fifty thousand pounds! It hardly seemed there was so much money in the world.

By this time the plane was about five hundred feet up, and beneath Jock could see a pale grey riband which was the road. He leaned out and caught a glow of headlights from a car that was speeding eastwards.

"There she is!" he cried. "You're right. She's going to Plymouth. At least she's on the Princetown road. And, my word, she's shifting."

"Let her shift. This bus is good for one hundred and twenty." He advanced the throttle and the great 250 horse-power engine filled the night with its thunder. In almost no time they were above the car.

"It's the same one," snapped Jock.

"The same one. What do you mean?" Jock quickly told him of the big car and its red-haired driver, and heard Hanley whistle softly.

"What are you going to do now?" Jock asked.

"You'll see," said the young pilot grimly. The big car was travelling at a furious pace. Wistern Wood was only a mile away, and Jock realized that the thieves hoped to reach its shelter where the car would he hidden by the trees. But before he could tell Hanley he felt the plane swoop downwards. For a moment he held his breath, waiting for the crash which seemed certain.

It was not the plane that crashed. As one broad wing swept across the car, almost touching it, the driver lost his nerve. Or perhaps he merely tried to swerve out of reach. Hanley brought the big machine up again in a perfect curve, and Jock saw the car strike the low bank at the edge of the road. She leaped high into the air, coming down with fearful force on her side and spilling her occupants like a child's bricks from an overturned box.

"Got 'em," snapped Hanley in sharp triumph. "Now if I can only find a landing-place." He switched on his lights and circled.

"A field!" he cried suddenly as the plane passed above a dry stone wall enclosing a pasture. "Plenty of room here," he went on, and next moment had cleverly set the plane down on the rough grass. In a flash he was out.

"Stay by her, Freeland," he ordered. "I'll go and clear up the mess. I won't be long." Picking up his flash-lamp, he hurried away in the direction of the road.

Fancy getting into a show like this! And only an hour earlier he had been lamenting the dullness of his holidays.

Time passed and Jock began to grow a little anxious about Hanley. And yet, he felt, there was no reason to be anxious, for Red Head and his companions must certainly have been stunned or otherwise damaged by the spill. All the same, he sighed with relief as he saw at last a light show over the wall. Some one was climbing over into the field.

A moment later a figure appeared within the flood of radiance cast by the powerful electric bulbs. A man was hurrying towards the plane carrying under his arm a good-sized box or parcel.

Jock stared. This was not Hanley. His heart seemed to jump straight up into his throat as he recognized the huge red-headed driver of the wrecked car.

FOR the moment Jock was so overcome with surprise and fright that he could not move. If Red Head had been coming quickly he must have seen the boy, but he walked so slowly that Jock had time to recover.

Jock realized that Finch Hanley's plans had gone wrong and that the big red-headed thief had, in some way, got the better of him. The question was what to do—whether to slip away out of the plane and go to Hanley's help, or to remain where he was.

"Stay by her." Suddenly he remembered Hanley's order as he had left, and instantly made up his mind to stay. But not where Red could see him. In a flash he flung himself down and crept aft. This was a mail plane, and there was a covered compartment in the rear where the bags could be stored. Jock slipped into this and pulled a tarpaulin over himself.

He was barely hidden before Red reached the machine. Red was breathing heavily and moved with a slowness which was in strong contrast to his energy when Jock had first seen him a few hours earlier.

"Must have got a bad bump when the car upset," thought Jock. "I wonder what he's going to do now." What Red did was to switch on, then go round in front and pull over the prop. The engine, still hot, burst into life, and next moment Red was scrambling into the pilot's seat. He advanced the throttle, pulled hack the stick, and almost before Jock knew it they were in the air.

Jock lay very still. Things had happened so quickly he was half stunned. Here he was, in a stolen plane, with a thief as pilot, driving away through the night towards some unknown destination.

It was not his aunt Jock was worried about. All his anxiety was for Finch Hanley, whom he thought of as lying stunned, perhaps badly hurt, by the upset car. Though he had known Hanley for less than half an hour he had already come to like him, and the fact that it was Jock's father who had taught Hanley to fly made a sort of bond between them.

After a while he crept a little way out from his hiding-place. He was desperately anxious to know which way they were going, but did not dare to raise himself high enough to look over the edge of the cockpit. Red, however, clearly had his destination fixed, for he was flying fast and straight. Judging by the chill of the air, he was pretty high, too.

Not being able to see where they were going, Jock turned his attention to the pilot. He noticed that the man sat slumped down in his seat and that now and then he swayed forward. He was evidently in pain. Presently Jock spotted something else. By the dashboard light he could see that the left leg of Red's trousers was darkly stained. The man was wounded, and blood was still running from the wound. In spite of everything, Jock could not help admiring the man's pluck.

The plane roared through the night. The sky was clear, and, looking up, Jock studied the stars. As we have said, he had done a deal of flying with his father, who had told him something about night-flying and navigation. By degrees Jock gathered that they were flying almost due north, and it seemed to him that Red must be making for Bristol.

The minutes dragged by, and Jock, glancing at his wrist-watch, saw that they had been flying for nearly an hour. They must be far up over Somerset by this time. Then suddenly the plane lurched. Red had fallen back in his seat, and in doing so had dragged the stick back. The plane was rocketing upwards.

Jock knew exactly what would happen. She would lose flying speed and drop into a spin. In a flash he was on his feet and had leaped forward. All these big planes have dual control, so all Jock had to do was slip into the seat alongside Red. He grasped the stick, pushed it slowly forward, and at once the plane came back to a level keel and drove steadily on.

Jock turned to Red and saw that his big face was horribly white. The man was still conscious, but only just. His intensely blue eyes were full of amazement. Jock leaned across and spoke into the man's ear:

"Stay where you are. I can keep her going." Red tried to speak, but though his lip moved, Jock could not hear what he said. Then he collapsed altogether.

Jock had at least as much pluck as the average boy, perhaps more than most. And he had the great advantage that he was familiar with the controls of an aeroplane. Yet to merely say that he was scared is putting it mildly. Here he was, in sole charge of a big machine thundering through the night. He did not know where he was or where Red was meaning to take the plane, and—when he glanced at the petrol gauge—he saw that there was not more than enough fuel for a couple of hours' flying.

Jock looked over and saw that they were flying over flat country at a height of about three thousand feet. Here and there he caught the lights of villages, but there was no sign of any large town. Away off to the left was the sea. The moon had risen and its pale light silvered the vast plain of water.

"Must be the mouth of the Bristol Channel," Jock said to himself. "Let me see, there's one good-sized town, Burnham. I ought to sight that pretty soon." But he was not so far north as he had thought, and twenty minutes passed before he saw the glow of a lighthouse and knew he was reaching Burnham. The petrol was sinking fast, and suddenly it occurred to Jock that perhaps Burnham had an aerodrome, and that he might land there instead of risking the flight to Bristol. He headed straight for the town, but to his dismay could see no sign of any aerodrome, or indeed of any place where it seemed safe to bring the plane down.

FOR a moment Jock felt again that nasty sinking, but he fought it successfully, and, as if by way of reward, suddenly saw beneath him a great stretch of smooth yellow sand. The tide was out, and the sands stretched for miles. They were wide, too, for in some places there looked to be a good half mile between the cliffs and the sea.

In a flash Jock took his decision. He would never find a better place to land, so, throttling down the engine, he pulled the plane round and began to descend. At first he pushed the stick too far over, and the plane's nose dipped and the whistle of the air in her wires warned him he was going far too fast.

"It's steady does it," said Jock aloud, as he racked his brain to remember everything he had been told. The wind. He had to head into it. That was the chief thing to remember, and, luckily for him, the ripple on the sea told him that the light breeze was coming from north of west. The moonlight was horribly treacherous, still it was better than nothing. He switched off and glided down.

The landing speed of a plane such as Jock was flying is about forty-five miles an hour. It is easy to imagine the crash if any mistake is made. Jock's heart almost ceased beating as he neared the ground. When it seemed that the plane's wheels were almost touching he eased the stick very gently, and went skimming just above the beach. Next moment he felt the wheels touch.

It was far from a perfect landing. The big plane ballooned, that is, jumped several feet into the air, then settled again with a bump that made Jock's teeth rattle. But no damage was done, and a few seconds later she had come safely to rest midway between the sea and the cliff.

For a full minute Jock did not move. He simply couldn't. The strain had been heavier than he knew, and he felt giddy and a little sick. That soon passed, and the first thing he did when he could scramble out of his seat was to turn his attention to Red. The big man lay slumped back in his seat. His eyes were closed, and for a horrid moment Jock thought he was dead. But presently Jock saw he was breathing.

Jock took out his knife and slit open Red's left trouser leg. Just above the knee was a great jagged gash. Jock's eyes widened as he saw the extent of the injury.

"My word, this chap's got pluck," he muttered as he began hunting round for some sort of bandage. He found a first-aid kit and it did not take long to douse the cut with iodine and strap a bandage tightly over it. Red was still insensible, and Jock wondered what he had best do. He did not like to leave the man, yet knew, of course, that he ought to get help.

All of a sudden his glance fell on the case which Red had been carrying, and he felt sure it must be the jewel box which Finch Hanley had failed to fetch from the car. He picked it up and, stone. Then dropping back he stood for a minute, fixing the spot in his mind. This was not difficult, for there was a long, queer- shaped rock lying on the beach just below the cleft, and a tree, a mountain ash he thought, growing just below the top of the cliff on a ledge. Thrusting a few pebbles into the empty box so as to make its weight right, he closed the lid and hurried back to the plane.

Red lay exactly as Jock had left him, but Jock saw that he was breathing more easily and that his face was not quite so ghastly as it had been.

"He's better," said Jock thoughtfully. "I believe I can leave him now." And then he got a shock, for just then Red's eyes opened and he looked up with a faintly puzzled expression. Then he smiled.

"So you made it, son?" he said.

"Got down, you mean?" Jock replied.

"That's what I mean all right, and I'll say it was lucky for me I shipped a pilot." He paused and gazed at Jock.

"Aren't you the chap who told me the way to Taverton?"

"Yes, only you weren't going there," said Jock bluntly. Red merely laughed.

"Oh, I might have been," he replied. "But I had a job to do first."

"A rotten job," returned Jock. Red shrugged.

"That's a matter of opinion, son, but we won't argue. At least not until I've thanked you for saving my worthless carcass."

"Perhaps I was thinking of mine," returned Jock, but Red took no offence.

"Whatever you were thinking you did a good job. Who taught you to fly?"

"I've never been taught, but I've been up with my father." There was real admiration in Red's blue eyes as he stared at the boy.

"And you picked a landing-place and brought this big bus down safely!" he exclaimed. "That was as good a bit of work as I've seen for a bit. And I know what I'm talking about. I was flying in the war." Jock flushed a little and changed the subject.

"What about Hanley?" he demanded.

"The pilot, you mean. Oh, he's all right. I had to tie him up again, but I didn't hurt him." Red fell silent, with his eyes fixed on Jock, and Jock did not speak either. He did not know what to say.

"And what am I going to do with you?" Red went on presently. "See here, if I turn you loose and give you money for your fare, will you go home and keep your mouth shut?"

"No," said Jock curtly. Red laughed rather ruefully.

"I didn't suppose you would. In that case you'll have to come with me."

"Where?"

"That 'ud be telling," replied Red, with a grin. "It isn't far, anyhow, and, thanks to you, I'll be able to finish the trip in the plane." Again he considered. "See here, I can't leave you on the beach, for you'd spot where I went and start someone after me, and that wouldn't suit my book at all. On the other hand, I don't want to tie you up or anything of that sort. Will you give me your word not to try to escape?"

Jock frowned. He did not know what on earth to say. Red might be a thief but he seemed a very decent thief, and he evidently wanted to treat Jock decently. Yet if he gave his word Jock would have to keep it, and what would happen when Red found that the jewels were gone?

For a moment he thought of making a bolt, but Red divined his intention and stretching out a huge hand caught him by the arm.

"No," he said quietly. "Whether you give your parole or not you've got to stay by me."

JOCK thought hard. He hated the idea of being tied up and carried like a pig in a net without a chance of seeing where they were going. Yet if he gave his promise not to escape he was even worse off, for, sooner or later, Red was bound to find out that the emeralds were missing from their case. He decided to bargain.

"I'll promise not to try to bolt until we get—wherever we're going. Will that be enough?"

"Quite enough," replied Red. He chuckled rather grimly. "By the way, what's your name?"

"Jock Freeland."

"Any relation to Captain Ronald Freeland?"

"He's my dad. Did you know him?"

"Met him once. A good man. Is he alive?"

"Yes, he's got a job in Persia."

Red nodded.

"I'm not going to tell you my name, but you can call me Red if you like. Now we must be shifting." He looked at the petrol gauge and pursed his lips.

"Just enough to take us there, I reckon," he remarked.

"But you can't fly her," said Jock bluntly. Red laughed. It was marvellous how he had recovered.

"If I can't you can take on again, Jock, but I reckon I can handle her all right."

"What—with that hole in your leg!"

"You've patched it up. Wish you'd pull over the prop for me, Jock," Red added. "I'm not very good on my pins." Jock looked at him sharply.

"You aren't afraid I'd run?"

"No," said Red calmly, and Jock climbed out and did as Red had asked. When he had got in again Red advanced the throttle, and the big machine started forward. Next moment she was in the air and Red headed her out to sea.

"Yes, we're going across to Wales," he said, answering Jock's unspoken question. "Ever been there?"

"No," Jock answered truthfully.

"All the better for me," said Red with a grin. It was a most pleasant and infectious grin, and Jock could not reconcile it with the idea of this man being a thief. He took his seat alongside the other and said no more. It was barely twenty minutes before Jock saw the lights of a big town beneath them. Behind were high hills.

Red, flying very high, crossed the hills and kept on northwards. Beneath him Jock saw rivers, silver threads in the moonlight, hills, and once a good-sized lake; then they were over a great stretch of high moorland, and all of a sudden Red cut out and began to descend.

They were dropping, Jock saw, into a hollow, and beneath was a house half hidden by trees. In front of it lay a good-sized stretch of grass which sloped to a swift brook. As they came close to the ground Red switched on the lights and next moment made a perfect three-point landing.

"Here we are," he said cheerfully. "And here's my housekeeper coming to meet us."

Jock looked at the man whom he could see plainly in the glare of the wing lights. A tall, lean fellow of somewhere between thirty and forty, with a long, narrow face, a beaky nose, and tight-lipped mouth. Jock did not like the look of him.

"What's wrong, boss?" asked this man as he reached the plane. His voice was as harsh as his face.

"A heap," replied Red carelessly. "Car went smash. But don't worry, Jasper. I've got the stuff."

"You got something else," said Jasper, fixing his hard eyes on Jock.

"The lad's all right," replied Red. "You'll treat him decently, Jasper, for if it hadn't been for him, I'd have been busted higher'n a kite. But he'll have to stay here a day or two until things are fixed up. Put him in the top room, then come back for me. I've a hole in my leg and can't walk."

Jasper beckoned to Jock and Jock climbed out and went with him to the house. It was bigger than he had thought, and looked solid and comfortable. Creepers covered the grey stone walls and there were flower-beds beneath the windows. The front door opened into a square hall, the walls of which were covered with various birds and beasts beautifully set up.

But Jasper did not give him the chance of examining these things. He took him up two flights of stairs to the top of the house, opened a door, and signed to Jock to go in. So far he had not said a word, but now he spoke.

"I don't know who you are or why Red brought you. But I'll give you a word of warning. Try any monkey business and you'll be sorry you were born." Jock looked at him.

"Your boss told you to treat me decently. Do you call that sort of talk decent?" Jasper's greenish eyes narrowed.

"You crow loud, my cock sparrow. Likely you won't have so much to say after you've been here a week." Then he went out, slamming and locking the door behind him. Jock sat on the bed.

"I'd better have kept my mouth shut," he said to himself. He was tired and sleepy and the bed, though narrow and hard, had clean sheets. Jock stripped to his under-clothes, had a wash, and was just turning in, when the key turned, and the man Jasper came in again.

"Boss said you was to have some grub," he remarked sourly, and dumped down a tray on which was a plate of cold meat, bread, butter, and some rather mouldy-looking cheese. Jock thanked him politely, but Jasper only scowled and went off, and again the key turned in the lock.

Jock was not hungry. He blew out the candle, but now, instead of turning in, went across to the window. The moonlight showed that it was quite thirty feet from the ground. It showed something else, too—four stout iron bars fastened across the casement.

Jock tried them, one by one, but they were firm as the stout pine timber to which they were fastened. His heart sank. So far, it seemed, they had not found out about the emeralds, but Jock did not like to think of what Jasper would do when he discovered how they had been tricked. Red himself was a decent sort, but Jasper was a brute.

"He'll try to make me tell what I've done with the stones," Jock said to himself. "My only chance is to get away before he finds out."

JOCK had Scottish blood in his veins. It was that which gave him the dogged streak which never let him allow that he was beaten. He had made up his mind to escape, and, if it were humanly possible, he would do it.

The first thing was to find out how the bars were fastened. It was too dark to see, but feeling with his finger-tips, he was greatly relieved to find that they were screwed to the wood. Out came his knife. It was a biggish knife and, as it happened, one blade was broken off short and could be used as a screw- driver.

It was not as easy as he had hoped. The screws were rusted in and refused to budge. It would have been all right if he had had a real screw-driver, but the steel of the knife blade was brittle, and he was terribly afraid of breaking it. Then a bright idea came to him. He had been dry-fly fishing the previous afternoon, and still had in his pocket the little corked tube of thick paraffin which he had used to oil his flies. He got a feather out of the pillow and dabbed some of this oil on the heads of the screws and the woodwork around them.

While this soaked in he took the sheets off the bed, laid them on the floor, and began to cut them into strips.

Each he split into four and twisting the strips, knotted them firmly together, making a rope quite long enough to reach the ground. When he had finished it he tied one end to a window bar and tested it yard by yard. It seemed rather flimsy, yet he reckoned it would hold his weight.

Now for the screws. To his delight, the oil had done the trick, and the first screw came out easily. But the second—there were two to each bar end—was obstinate, and when Jock put his weight upon the knife suddenly there was a sharp snap, and the rest of the blade broke clean away.

For a moment Jock was utterly dismayed, for it seemed as if his last hope had gone, yet again the dogged streak came to his rescue. There was another blade, and he was on the point of breaking it off when he had a fresh inspiration. Instead of trying to turn the screw, he decided to cut it out.

The wood surrounding it was almost as hard as iron, but by degrees Jock carved it away, until he had a hole half an inch deep on one side of the screw.

Now, if he could only find a lever of some sort.

It did not take him long. The bedstead was an iron one, and pushing off the mattress, Jock took off one of the metal slats, and found that he had just the tool he wanted. He jammed the end under the screw-head, and worked until at last the wretched thing began to loosen. Then he took hold of the bar and pulled. There was a snap, which sounded so terribly loud that Jock stood breathless, quite expecting some one would rouse. But the silence remained unbroken, and Jock began to pull on his clothes.

All this had taken a very long time, and the false dawn was already dimming the stars. Jock had meant to be well away before daylight, yet, in spite of his hurry, he took good care to tie his sheet rope very firmly to a bar. At the last minute he remembered he had no food. So he filled his pockets with the bread and meat from the tray. Then he threw the end of his rope out, and squeezing between the bars, went down hand over hand.

To his horror, he found that there was a first floor bedroom window exactly below his. The upper part of the sash was open, so it looked as if some one was sleeping in the room. The blind was down, but not all the way. Each instant Jock expected to hear a shout, but there was no sound, and he reached the ground in safety.

He stood a moment looking round to get his bearings. All was open ground in front, but what Jock wanted was cover. There was a clump of laurels to the left, and he went swiftly towards it. His one object was to put as much distance as possible between himself and the house for that great white rope which, of course, he had been unable to remove, was a regular advertisement of his escape.

His troubles were not over. With a snarling growl a dog came at him out of a path leading through the shrubbery. A huge tawny beast with blood-shot eyes.

Jock had not even a stick—not that a stick would be much use against a creature like this—but he had something better, a knowledge and love of dogs. Instead of bolting he stood perfectly still, facing the great hound.

"Hulloa, old chap," he said in a casual sort of voice. The dog stopped too, but the growl still rumbled in his throat. "It strikes me you look a bit hungry. I don't expect you've had any breakfast. What about a bit of mutton?" Very quietly he slipped his hand into his pocket and brought out a slice of meat. And all the time kept on talking in the same slow, gentle voice.

He stretched out his hand towards the dog with the meat lying in the palm. The dog stopped growling and came a step nearer. He was hungry and the mutton smelt good. Jock stood like a statue, and step by step the dog approached.

"If he'll only take it!" thought Jock. Even now he could not tell what the dog would do. He might snap, and in that case Jock would lose his hand, for the dog's jaws were as powerful as those of a wolf.

He did not snap; he took the meat. He ate all that Jock had, and before he had finished Jock was stroking his massive head. When at last Jock moved away the dog followed him. At the end of the path was a wicket gate leading into a wood. Jock shut it firmly in the face of his four-footed friend, walked quietly till he was out of the dog's sight, then started to run.

The sun was up, it could not be long before his escape was discovered and then they would be after him. The path wound among the trees and he could not tell in the least where he was going.

All of a sudden he came out into the open. In front was a river thundering in a foaming rapid between high banks. Once there had been a foot-bridge, but some winter flood had carried it away. Jock pulled up short. There was no way across. At that moment he heard a deep baying in the distance. The great hound had been set on his track.

JOCK looked at the river, the long streaks of yellow foam gleaming in the light of the newly risen sun. He knew he was in a very tight place.

The question was whether to go up-stream or down. That did not take long to decide. Below the rapid there would be smoother, slower water, and Jock, a good swimmer, felt sure that he could cross in that way. Turning sharply to the right, he plunged into the wood and ran.

It was bad going. There was a lot of thick bracken and undergrowth which slowed him a lot. The worst of it was the noise he could not help making, crashing through it.

He heard the dog again. The deep bell-like bay rang through the calm air of the early morning, and the sound was nearer than before. Jock was getting blown. His build was too square and sturdy for sprinting. One thing was in his favour. The hill was not so steep, while the river was less noisy. He felt he must be getting near the end of the rapids, and if he could only find a still pool he meant to take to the water.

The baying broke out afresh and this time it was ahead of him. With a horrid shock Jock realized that Jasper must have guessed his direction and taken a short cut. Now there was nothing for it but the river, and wheeling to the left Jock plunged down the steep bank.

The sight was not a pleasant one. Though he was below the actual rapid, the river, which was very full, was running narrow and deep with a speed far beyond the power of any swimmer to fight across it. Yet Jock had no choice. He plunged in.

At once the strong stream seized him and carried him down like a chip. It was all he could do to keep his head up while the current took him down.

Looking up, he saw the bushes part as the big hound came leaping down the bank. Next minute he was carried round a bend, and in spite of the cold and the danger he almost laughed to think how he had fooled Jasper.

"He'll think I'm drowned," he said to himself, and next moment found himself caught in a whirlpool and fighting hard to save himself from being actually drowned. His wet clothes felt heavy as lead, but just as he was almost giving up he managed to grab a big bough which overhung the pool. With the help of this, he pulled himself out of the swirl and got close to the bank. He could not get ashore because the bank was too high and steep, but he hung on and tried to get his breath back. He was badly blown.

Suddenly a stone came bouncing down the steep bank above. It crashed through the tree, missed Jock's head by a yard, and plumped into the water. Jock looked up in a fright, and nearly cried out, when he saw the long legs of Jasper just above him.

"I knowed you weren't drowned," said the man. "Come out of that." Instead of coming out Jock went in. He released his hold on the branch and struck out furiously.

"No you don't," snapped Jasper and dropped down the bank on to the branch. But the branch was not built to stand Jasper's weight. With a loud crack it broke off and together with Jasper soused deep into the pool.

Jock's spurt had taken him clear of the suck and he was carried swiftly down a long swift stickle. Glancing back, he saw Jasper clinging to the branch following him.

Fright gave Jock fresh strength. He swam as he had never swum before, and gained rapidly on Jasper. Next minute he was swung round another curve and found himself in a big circular pool, quite surrounded by trees.

"I say, isn't it a bit early for a bathe?" came a voice, and Jock saw a tall, slim, fair-haired boy seated in what looked like a large wicker basket, with a fishing-rod in his hand.

"I—I'm not bathing. They're chasing me," Jock answered hoarsely. He saw the other boy stiffen, saw him quickly lay down his rod and pick up his paddle, and knew that he had spotted Jasper.

"All right," said the fair-haired boy. "I'll give you a hand. Get hold of the stern and I'll tow you ashore." Jock gratefully caught hold of the gunwale of the queer craft.

"You can't get in," the other explained. "A coracle only holds one. And for any sake don't upset her. I don't want to lose my rod." Balancing the tiny boat in a way that seemed to Jock nothing short of a miracle, the tall boy wielded his paddle vigorously, and in a very short time had Jock ashore on the far bank. Jock scrambled out, dripping and shivering.

"T—thanks awfully," he said between chattering teeth.

"Who's your friend on the branch?" asked the other. "Strikes me he isn't doing much chasing. I don't believe he can swim. Hadn't I better pull him out—?" He broke off. "Hulloa, what's this?" he exclaimed. The big hound had suddenly appeared on the far bank. Without hesitation he plunged in, swam out to Jasper, caught hold of his coat, and began to tow him ashore.

Jasper reached shallow water and scrambled out. He turned and glared at Jock.

"You're clear for the minute, but don't fancy I've done with you yet. I told you that if you played the fool you'd be sorry. And you will." He swung round, plunged in among the trees, and vanished. The dog followed. The tall boy turned to Jock, and the smile was gone from his face.

"You're right," he said gravely. "That chap's dangerous." Then he saw how white Jock was. "But you're all in," he added. "Come up to the house and I'll find you some dry kit. And I'm crazy to hear what's happened. We don't get much excitement in these parts."

A NARROW path led steeply tip through hanging woods. At the top of the hill they came upon a road, and a little way down it was a gate leading into a garden which sloped upwards to a small but comfortable-looking house.

"This is our place," said the tall boy. "Dad and I live here, but he's away just now. He's Major Bellingham; I'm Tim."

"My name's Jock Freeland," Jock told him.

"Jock," repeated the other, and laughed. "Suits you down to the ground. I bet you're Scotch."

"Half," said Jock. "But dad's English. You're Irish, aren't you?"

"My mother was," said Tim. "She's dead," he added quietly.

"So's mine," Jock answered. Tim looked at him and just nodded. But in that moment began a friendship which was to lead to things which neither of the boys could possibly foresee.

"Got any fish, Master Tim?" came a voice from the porch, where a man, who looked like an old soldier, was polishing the brass bell-pull.

"One, Ballard. A big un. Here he is." The man turned and his eyes widened. Then he smiled, and Jock liked his smile.

"He's wet, anyway. Did you fall in, sir?"

"Had to," said Jock with a grin.

"Tell you afterwards, Ballard," said Tim. "I'll take him up and get him some dry things. Tell Margaret we're both jolly hungry.

"Ballard was dad's batman in the army," Tim explained. "He and his wife run the house. Come on up." In his bedroom Tim soon raked out a change for Jock.

It was a great relief to get out of his soaked clothes and into dry ones, and by the time Jock had changed, breakfast was ready. A big dish of well-grilled bacon, crisp toast, home-made bread and butter, marmalade and tea. Tim did the honours, and would not let Jock talk until he had finished his share of the bacon, then when they got to the second course of bread and marmalade he began to ask questions.

Jock told him the whole story, from the time he had first met Red in the car until he had escaped from Red's house and taken to the river. Tim stopped eating, and leaned forward with his chin on his hands and his Irish grey eyes shining. He never said a word until Jock came to being left alone in charge of the plane.

"And you got her down without a crash!" he exclaimed.

"More luck than skill," said Jock, but Tim shook his head.

"Don't tell me. I know."

"You fly?" asked Jock quickly.

"A bit. I'm mad on it," was Tim's answer. "But go on." Jock went on. When he had finished, Tim drew a long breath.

"My word, you have been mixing it. I say, what do we do now? You can't leave fifty thousand quids' worth of jewels stuck in a hole in a cliff. And there's another thing. This fellow, Red, will know just where to look for them. I mean, when he finds the casket empty."

Jock nodded.

"I've thought of that. Yes, he'll know that I hid them somewhere near where we came down, because that was the only chance I had. But he'd have a job to find them."

"Still, he'll look," said Tim, "and I'll lay he won't waste much time in looking."

"He's got a bad hole in his leg. I don't believe he'll be able to do much for a day or two."

"Then he'll send Jasper or one of his other pals. See here, Jock, the thing for us to do is to get to that beach as quick as ever we jolly well can. We have to beat 'em to it."

"We," repeated Jock. "It's nothing to do with you, Tim. And, besides, what would your father say?"

"If dad was here he'd have started already," Tim declared. "And since he isn't, it's up to me to lend a hand. Don't say no, Jock. It's the first bit of real excitement that's ever come my way."

"I'll be jolly glad to have you," said Jock. "But I say, don't you think we ought to go to the police."

"What would be the use?" retorted Tim. "Griffiths, the local constable, has about as much brain as a tortoise. If we tell him he'll go all the way to Llandovery to telephone to the Chief Constable. Then the Chief Constable would have to come and see us. Why, they wouldn't get started until to-morrow, and by that time Red will have been there and gone."

"I expect you're right," said Jock slowly. "But suppose we tackle the job, how are we going to manage it? I haven't a bob. And we shall want a lot of money for fares and one thing and another." Before Tim could answer, Ballard stuck his head in.

"Have you finished, Master Tim? If you have I'd like to clear. And here's the newspaper."

"Give us five minutes, Ballard," said Tim. "We've been yarning and forgotten the time. Is there any news?"

"Big jewel robbery. Plane tricked down by false landing lights on Dartmoor, and Lady Meripit's emeralds stolen. It's in the stop press." Tim grabbed the paper and opened it.

"Here it is. Here's the yarn. And, Jock, listen. There's five thousand pounds reward for the recovery of the emeralds."

"Five thousand pounds!" repeated Jock. "Why, if I had even half that, dad could come home and buy that partnership he's so keen on." Tim brought his fist down on the table with a thump that made the crockery rattle.

"Then, by gum, you shall earn it, and I'll help." Even stolid Jock showed signs of excitement, but he did not let it overcome his common-sense.

"I'm as keen as can be, Tim, but you haven't answered my question. Where are we going to get the money? Have you any?"

"I've got about thirty bob. Can't get any more till dad comes back."

"That's not enough," said Jock firmly. "Remember, we have to go all the way round by Bristol." Tim bit his lip. Then suddenly he jumped up, knocking his chair backwards.

"I've got it. We'll bag the plane. I can fly her all right."

Jock stared. Then all of a sudden he shook his head.

"It's no good. Even if we could get her there's only petrol for about half an hour left in her tank." Tim was not at all dashed.

"That don't matter. Dad and I are members of the Llanfechan Flying Club. The aerodrome's less than twelve miles from here and the instructor's a pal of mine. We'll fly her over there, tell him the whole yarn, and he'll give us all the petrol we want." Jock grinned.

"You've an answer for everything, Tim. Well, I'm game if you are. Only before we leave I want to do two things. First, send wires to my old aunt to tell her I'm still alive, and to Finch Hanley, who'll probably be at Taverton. Then I think we ought to leave a note for your father so that he'll know where we are in case anything goes wrong."

Tim nodded his approval.

"Ballard will send the wires if you'll write them. I'll write the note, then we'll shove along."

Ten minutes later the two left the house and headed for the pool where they had left the coracle.

AS they neared the edge of the pool Jock pulled up.

"One thing you've forgotten. The coracle won't hold us both."

"Don't worry, I didn't forget the string," replied Tim, taking a ball of stout string from his pocket. For a moment Jock looked puzzled, then he nodded.

"I see. One goes over, the other pulls the coracle back."

"Go up one," grinned Tim, and got into the queer little bowl- shaped boat. He paddled across, trading the string behind him, and Jock pulled the coracle back. It was the crankiest craft he had ever sat in, and it beat him how any one could fish from it, but Tim declared it was quite easy when you got used to it.

Tim chatted gaily as they went up through the steep woods opposite. The two might have been off on a picnic instead of the extremely risky venture they were engaged on.

Gaining the top, Tim stopped talking and went forward cautiously. He led the way, for he knew the lie of the land better than Jock.

"I've been to Garve House," he told Jock, "but not since the present man has had it."

"What's he call himself?" Jock asked.

"Spain, but I'll bet that's not his real name."

"He's a queer chap," said Jock. "I must say he was very decent to me."

"I doubt if he will be this time—that is if he catches us," Tim chuckled.

"I'm not worrying about him," said Jock. "It's that chap Jasper. He's a nasty piece of goods."

"I don't believe he'll be here at all," declared Tim.

"Then there'll be somebody else. You can just bet on that," declared Jock.

"We shall soon see," Tim said. "We're coming to the edge of the wood. Duck down and creep through the bracken." They ducked and crept, and presently were on the edge of the wood. The meadow was in front of them, Garve House to the right, and to the left, about a hundred yards away, the brook which ran into the bigger river just below the pool where they had crossed. The plane lay almost in front of them at a distance of about a couple of hundred paces.

"There's a man working on it," whispered Tim. "What luck! He's filling the tank."

"Luck, do you call it?" growled Jock. "How do you think we're going to get it away with that chap hanging round?" Tim was not at all dismayed.

"Let's go round by the brook. We can creep up the bed of it, rush him, and tie him up."

"And then sit there for ten minutes while the engine warms up?" asked Jock sarcastically.

Tim looked a little dashed, but not for long.

"I expect the man will start warming her up as soon as he's filled her. Your friend, Red, will want to get rid of the machine as soon as he can. So long as it's here it's evidence against him." Jock frowned.

"You may be right about that, but anyhow your plan's too risky. It's quite a long way from the brook to the plane, and he'd be pretty certain to spot us. Then he'd lay for us with a spanner, and what chance should we have?"

"He wouldn't have an earthly against the two of us," declared Tim. "And if we don't do that I'd like to know what else we can do."

"We might create a diversion, as my dad used to say. Fire a gun or something like that."

"We haven't a gun, and there's no time to fetch one," said Tim flatly.

"We'd get one in the house," said Jock. Tim's eyes widened.

"For a canny Scot you've got large ideas," he said. But Jock was not listening. He was frowning, thinking hard.

"Tell you what, Tim, I think I've got it. When I came through the shrubbery this morning, just after I'd got away from the dog, I spotted a big pile of branches. If I was to run up there and stick a match into the pile there'd be a jolly fine bonfire. That might fetch the chap."

"It might work." Tim's voice was a little doubtful. "We'll try it anyway."

"No need for you to come. I can do it," said Jock.

"Yes, and run into trouble. See here, Jock, we're in this together, and we stick together." Jock grinned. The more he saw of Tim the better he liked him.

"All right," he agreed. "Only if the dog comes out, remember he's my pal, not yours."

"I'm not jealous," laughed the other. "Come on."

It did not take long to make their way up through the wood to the wicket gate. There they paused and listened, but there did not seem to be any one about, so they went quietly through it and crept up under the garage wall. That hid them from the house.

There was the pile of branches stacked up six feet high. Jock peeped round the end of the wall, then finding the coast clear slipped out, and, striking half a dozen matches at once, thrust them into the heap. He waited only long enough to make sure the stuff was alight, then scuttled back. As the two raced through the shrubbery into the wood there was a crackle like fireworks behind them, but next moment this was drowned by the far louder sound of the plane's engine.

"There, I told you," said Tim, "He's warming her up. And as for that fire, he'll never hear or see it." Jock looked a bit worried.

"I expect you're right. We'll have to try your plan and go round by the brook."

"That'll work all right," said Tim confidently. "Anyhow the chap will never hear us."

"He won't hear us, he'll see us," Jock said. "There's no cover once we leave the brook.

"Don't grouse. We've got to have that plane."

It was all right down in the bed of the brook, for the bank was high enough to hide them so long as they kept their heads down. But it was difficult to run all doubled up, and some of the pools were quite deep. It was more than five minutes before they gained the spot nearest to the plane.

"My word, that fire's going great guns," said Jock as he poked his head up over the bank. "Look at the smoke."

"But the man isn't paying any attention to it," Tim answered. "It's no use waiting. Let's go," Jock caught Tim by the arm.

"Wait a jiffy," he whispered urgently. "He's getting up into the plane."

"Then the odds are he's starting," replied Tim sharply. "Come on, Jock, or he'll be away with her, and then our goose will be properly cooked." Instead of starting, the man switched off, and the silence that followed was broken only by the distant crackle of the bonfire. Jock's face lit up.

"That's better. Now he's bound to spot the fire. Yes, I told you so." The man was looking round at the great cloud of smoke which a faint breeze from the north-east was carrying towards the house. It was so thick that the house itself was almost entirely hidden.

"He's getting out. He's going to investigate," breathed Tim, who was quivering with excitement. "Now's our chance, Jock."

JOCK was as excited as Tim, but he did not show it so much. He waited till the man had nearly reached the edge of the smoke, then let go of Tim's arm.

"All right," he said. Tim went off like an arrow from a bow. He was in the plane before Jock reached it. As Jock ran round in front he saw Tim already in the pilot's seat.

"Can you handle her?" panted Jock.

"Rather. At least I can fly her. I don't know so much about navigating. But I say, the wind's all wrong. I'll have to turn her into it to get her up." Jock glanced round to see what the mechanic was doing.

"Then you'll have to be jolly quick," he said. "There are two men coming from the house. And one of 'em is Red."

"Red! I thought he was in bed."

"He isn't. He's walking with a stick. I don't know who the other chap is, but he looks hefty."

"Give her a turn then," cried Tim. Jock did so, and the engine, well warmed, started at once. Jock scrambled in. Tim advanced the throttle, and the roar became deafening as the plane began to move.

At present her nose was pointed towards the brook, but there was not space enough on the down slope for her to rise. In any case an aeroplane must take off into the wind, so Tim started to bring her round. But a plane doesn't turn like a car. She has to come round in a wide sweep. Jock was watching Red and his companion, and the moment the engine started the latter also started and came sprinting down the meadow with great strides. By the time Tim got the plane round, the man was quite close.

He was tall and powerfully built, and the savage look on his weather-beaten face augured ill for the boys if he once got his hands on them. He ran directly for the plane. She had not got her pace yet, and was bumping badly over the uneven ground. It looked all odds that the big man would reach her before Tim could get her going.

Tim kept his head admirably. Instead of turning the machine away and trying to escape, he deliberately swung her round and headed straight at the man. In order to escape being knocked down the man was forced to leap aside. His quickness was wonderful, and as the wing passed him he made a grab and caught the tip. His weight checked the plane, and if the wing had hit the ground would have stopped or upset her.

But Tim had spotted exactly what the man meant to do, and as the fellow seized the wing he quickly swung the machine in the opposite direction.

"He's down! You've bowled him over," shouted Jock. The left wing rising sharply had caught the man in the chest and knocked him sprawling. Before he could get up the plane was far out of his reach and travelling at thirty miles an hour. A moment later Tim raised the stick back, bumping ceased, and the big machine took the air. Jock leaned over.

"Good work, Tim," he shouted in Tim's ear. Tim grinned. His grey eyes were dancing.

"I knew we'd manage it," he shouted back as he circled upward. "I say, Jock, try and find a couple of helmets and a phone. We'll probably do a lot of talking, and I hate having to shout."

Jock nodded and clambered back into the after part of the plane. In a locker he found two helmets and phones and also a leather waistcoat and an overcoat. This was real luck for, even on a summer day, the upper air is distinctly cold. He put on the waistcoat and brought the overcoat for Tim. Then they put on the helmets, connected the phones and sat comfortably side by side.

"I'm taking her pretty near due south," Tim said.

"Where are we?" Jock asked. "I don't even know what county this is."

"Carmarthen," Tim told him.

"Then south is about right or a bit east of south. We passed over a big town last night. I expect it was Swansea."

"I don't know about that. It might have been Barry Dock or Cardiff. Where did you leave, Somersetshire?"

"A little east of Weston as far as I could gather. It was a biggish place and I spotted a lighthouse."

"You're a bit vague, old man," replied Tim. "If the place was Weston, we have to go a lot to the east of south."

"Let's try that first anyhow," said Jock. "If it's wrong we can go west down the Bristol Channel. I'm pretty sure I'd recognize the place. There's a queer-shaped rock on the beach and a mountain ash exactly above the hole where I planted the emeralds." Tim nodded and pulled the plane round until her compass showed south-east.

"First time I've ever flown a big bus like this," he told Jock. "Feels like a Rolls Royce compared with a baby car. But, my word, how she does travel!" He opened the throttle a little and the needle of the dial crept up to one hundred and twenty miles an hour. "We'll be there in about forty minutes," he added.

Jock was looking over the edge of the cockpit.

"There's a lake," he said eagerly. "It's the one we passed last night. We're on the right track."

"Then Cardiff's your town," Tim replied. The lake faded away behind them and hills rose in front. As they swept over the crest, the broad waters of the Bristol Channel showed in front, shining under the bright sun. They passed over Cardiff at about three thousand feet, and Tim held the big plane straight out across the Channel.

"There's my lighthouse," Jock said presently. "At least I'm pretty sure it's the one I spotted last night."

"That's Weston," Tim told him. "I'll keep just east of it, and we'll fly low up the beach until you get your landmarks."

At the pace they were moving they were across the Channel in about a quarter of an hour and Tim dropped lower and turned east, flying up the beach at a height of about five hundred feet, while Jock scanned the cliffs on the star-board side, watching keenly for the spot where he had set the plane down on the previous night. Tim came lower still and the plane roared along only a little above the level of the cliffs, startling the seabirds with the rattle of her exhaust. The cliff ran out to a point in front, and as they rounded this great mass of rock Jock exclaimed in dismay.

"There's a plane there already, Tim—on the beach. Do you see?"

Tim whistled softly.

"I see her all right. Yes, and two men searching the cliff. Looks to me as if your friend, Red, had stolen a march on us, Jock. What are we going to do? The beach is the only place to land, but it would be simply crazy to bump down on top of those chaps. With fifty thousand pounds at stake they won't stop at much."

JOCK knew Tim was right. With jewels of such immense value the thieves would not stop at much, and it was clearly out of the question to alight on the beach. On the other hand, there did not seem any other place where there was a chance of landing in safety, for all the ground above the cliffs looked rough and broken.

Looking down, he saw the men below staring up at the plane. He could not recognize their faces, yet one, it seemed to him, looked curiously like Red. Yes, it was Red himself for he was walking with a stick. He must have been mistaken about the men he had seen just before they left Garve House.

"Keep on," Jock said to Tim. "Fly right on and see if there's any place where we can land."

"There isn't," Tim told him. "The only thing will be to go on to the nearest aerodrome and get help."

"And by that time Red and his pal will have got the stones and cleared out."

"It's rotten luck, Jock, but I don't see how it can he helped. I'd only crash if I tried to put her down here." Jock's brain always worked best in a tight place. Now, suddenly, an idea flashed through his brain.

"Listen," he said eagerly. "Don't go on to Bristol. Throttle down and fly in a circle."

"Do you mean so that we can watch them?" Tim asked.

"No. I'm going down."

"Are you crazy?" demanded Tim.

"Not a bit. There's a parachute in behind. I spotted it when I was looking for the helmets."

"A parachute! Have you ever used one?"

"No, but I've seen it done ever so many times. I've helped a chap to put one on." Before Tim could say anything more, Jock had disconnected the phones, and scrambled back and was groping around in the after compartment of the plane. When he came back Tim saw that he had the pack strapped on his back. Tim was very upset.

"Jock, it's a beastly risk," he said as Jock reconnected the phones. "Even if the thing opens all right you can't tell where you'll drop."

"The wind's north-west," Jock told him, "so I shan't go into the sea anyhow. As for risks, well, we've taken a few already, and five thousand pounds reward is worth a few more. Don't worry, Tim. I shall be all right."

He was so confident that Tim felt a little happier. In any case Tim knew it was no use arguing. Though his acquaintance with Jock was only a few hours old, it had been long enough to realize that his new friend had a will of iron. Jock was speaking again.

"Go up to about three thousand, then come round right over the beach. That's where I shall get off. Afterwards you'd better fly to Bristol, and ask 'em to send help as quick as they can." Tim's lips set firmly.

"Right you are, Jock. I only hope we find you whole and not in small pieces." Jock laughed and Tim was inwardly amazed. Whoever was scared it certainly was not Jock.

Tim obeyed Jock's directions implicitly. He rose and circled while Jock watched for the right spot at which to make his start. He had again disconnected the phone. Presently he stood up. The chill air stung his face, but he paid no attention. He drew a long, deep breath, then stepped over the side of the cockpit as calmly as if he were getting off a train.

The wind whistled and screamed past his ears as he dropped into space. He yanked at the cord which would release the bundled parachute, yet nothing happened, and for a few horrid seconds he felt real panic. Then came the welcome crack and snap of the silk as it unfolded above him. The parachute opened and grew taut, and with a jerk the stout harness tightened around his body. After that he was able to breathe easily and found himself floating in mid-air as softly as a bit of thistledown.

The roar of the plane was still loud in his ears and looking up he saw it headed for Bristol, travelling at great speed. He grinned. "Stout fellow, Tim. He isn't going to waste time bringing help." Then he looked down. The robbers' plane was still on the beach but he could not see Red or his companion. The breeze was carrying him inland and they were hidden from him by the cliff.

A nuisance, this wind. Already he saw that, instead of landing near the edge of the cliffs as he had hoped, he would be taken at least half a mile inland.

The air grew warmer. Cradled in the harness, the descent seemed endless. Yet presently he was near enough to the ground to realize that he was really falling quite fast. He remembered something his father had once told him—that if you don't bend your knees there is every chance of damaging yourself badly. He found himself being swept across a rough looking field at a height of about a hundred feet.

He drew up his legs and almost before he knew it his feet had touched the ground. He flung himself flat and was dragged along for some distance. It was lucky for him that it was grass on which he had dropped for, if it had been hard ground, he would have been badly bruised. The great expanse of silk flattened against the ground and Jock was able to unstrap the catches and free himself from the harness. He did not wait to fold up the 'chute. That could be left till later. Picking himself up he ran hard for the edge of the cliff.

The distance was greater than he had thought. He was panting and drenched with perspiration by the time he reached the top of the cliff.

He looked over. There was nothing there at all, no plane, no men, not a living thing except a few gulls.

JOCK stared. He could hardly believe his eyes. He looked up into the sky but could see no sign of the robbers' plane. He certainly had not heard it go, but come to think of it the cliffs might have shut off the sound.

Anyhow, it was gone, and Jock's heart sank at the thought that Red must have found the emeralds and taken them away. In that case he feared they were lost beyond all hope of recovery, and with them went all chance of the reward. Jock himself was not a greedy sort, but it was his longing to get his father back to England that made him so desperately keen for a share of that five thousand.

All this passed through his mind in a flash, then he was running along the cliff top, looking for a place to climb down. His one idea was to find out whether Red had actually discovered the hiding-place. He found a gully and started down. It was a horrid, dangerous place for the steep slope was covered with loose shale. Yet for once Jock's usual caution deserted him and he clambered down at reckless speed.

The result was very near to being disaster, for the loose stuff began to slide under his feet, and if he had not managed to grasp a projecting rock which was solid enough to hold him, he would probably have been buried in the young landslide that roared to the bottom of the gully. This scared him, and the rest of the way he went more carefully. He ran down the bottom of the gully and out on to the beach. The small muddy waves of the Bristol Channel broke on the sand but, look as he might, he could see nothing else.

It occurred to him that Red might have left his companion to watch him, and Jock paused long enough to carefully survey the cliff face. But he saw no place where a man could hide, and feeling sure that there was no one in sight, ran down the beach to the spot where the odd-shaped rock lay. He got his bearings between it and the stunted tree on top of the cliff and climbed quickly up to the hiding-place.

He found it without trouble, and drew a long breath of relief as he saw that the stones with which he had wedged the mouth were still in position. Pulling them out he thrust his hand in and drew out the bundle of stones still wrapped in his own dirty handkerchief.

"Good luck!" he cried joyfully, and sliding down, waited a moment to take a glance at the sparkling gems. They were all there. "Won't Tim be pleased?" he said to himself, "and Hanley. Even if we share the reward between the three of us it'll be over sixteen hundred pounds apiece."

A shadow fell across him and he looked up. A plane, with engine cut out, was swooping down swift and silent as a vast hawk. Jock's heart turned over as he recognized it for the one he had seen on the beach little more than half an hour earlier. Stuffing the emeralds into the pockets of his jacket, half one side, half the other, he turned and ran for all he was worth for the cleft by which he had gained the beach.

From the first he knew it was hopeless. What could he do against a plane? Red had been too cunning for him. Red must have recognized the other plane at once and taxied away down the beach to a safe distance from which he could watch what was happening. Far easier to let Jock find the stones than spend hours in what would probably have been a vain search.

As Jock gained the mouth of the cleft he heard the plane land close behind him.

"Just as well chuck it, Freeland," came Red's deep voice. "You can't possibly get away from us." Jock knew it, yet he never turned his head but made a frantic run at the steep slope down which he had come. His rush carried him some twenty feet up the slope then, just as his outstretched fingers were almost touching the projecting spike of rock, the treacherous shale gave way, and he felt himself sliding downwards. As he reached the bottom a pair of hard hands gripped him.

"You young fool!" growled a harsh voice. "Didn't you hear what Red said?"

Jock was not done yet. Instead of pulling away he ducked down and drove his head into his captor's stomach. Down went the man flat on his back, and Jock spun round and made another dash up the slope. It was no good. That miserable shale again betrayed him and he slipped back once more, helpless, into the grasp of his enemy.

"Butt me in the stomach, will you?" The man's horny hand smacked Jock across the jaw with a force that made his head ring.

"Chuck that, Mark!" Jock had never yet heard Red angry, and the sound of his voice was almost terrifying. "Didn't I tell you I wouldn't have the kid hurt?" Red's very blue eyes were blazing. In spite of his lame leg he looked so formidable that the man named Mark shrank.

"He butted me in the wind," he said sulkily.

"Serve you right for not watching him. I told you he was a fire-eater." Red stood leaning on his stick, looking at Jock.

"Fortune of war, son," he said in a very different tone. "I'll have to ask you for those emeralds." Then as he saw Jock glance round—"It's no use, my boy. There's no one within sight or hearing. Give 'em up. I don't want to be forced to take them."

Give Jock a ghost of a chance and he would fight like a fury, hut now he was beaten and knew it. He pulled the emeralds from his pocket and handed them over.

"But I'll have them back, Red," he said very quietly. Red did not laugh.

"If you were five years older I believe you would," he answered candidly. "How the deuce did you get away with that plane—did you knock out the mechanic?"

"No. You'll hear about it when you get home."

"It'll be a long time before I see Garve again, Freeland," Red laughed.

"Let's go, Red," Mark cut in. "There'll be police planes out after us if we aren't sharp."

"Yes, I reckon we must be moving," said Red. "See here, Freeland, I don't want to take you with me and anyhow I don't suppose you want to go. But I can't have you running off for help. I've got to tie you up. Someone will find you before long."

"Better take him along and dump him somewhere," growled Mark. "He knows too much." Red turned on the man with sudden fierceness.

"Shut your mouth. Who's running this show?" he said in a tone which made the other shrink. Then he took some cord from his pocket. Mark put out his hand for it, but Red shook his head.

"I'll do the tying," he said dryly. "I don't want the boy left like a mummy. He's got more pluck than you, anyhow, Mark." Mark scowled, but said nothing, and Jock saw he was afraid of Red. Red directed Jock to walk out into the middle of the beach.

"They'll see you more easily," he explained. Then he made him lie down and tied his wrists behind his back and, afterwards, his ankles. He made good solid knots, but did not pull the cord brutally hard.

"So long, Freeland," he said. "No ill feeling, I hope."

"None at all," Jock answered. "All the same, I'll have those emeralds before I've done."

"I wonder," said Red, and with a last nod hobbled off to the plane and scrambled in. Mark followed, and Jock saw him pull over the prop. The engine roared, the plane began to move. It gained pace, rose, and turned north. Jock watched it rise to a great height and drive away across the Channel. As it disappeared in the distance a wave of bitterness swept over him, and for a little while he felt as if nothing mattered.

But that did not last long. Jock was not the sort to give up to despair. By this time Tim would be in Bristol. Help would come soon, then the wires would be busy, and pursuit organized. He could accurately describe Red's plane, and it would be watched for and spotted. He waited, with his eyes fixed on the eastern sky, hoping each moment to see Tim's plane appear. But it did not come, and the beach itself remained empty and deserted. This was evidently a very lonely spot.

The plash of the waves was growing louder, and when his eyes turned in that direction he got a shock. The tide was coming in fast, and the water was no more than twenty paces from where he lay. He realized with a nasty shock that the spot where Red had left him was below high-tide mark, and that within a very few minutes the rising tide would reach him.

Alone, he was helpless. Unless help came, and came soon, he was doomed to be drowned. Again he looked at the sky but, except for a few gulls, it was empty, and though there were ships passing up and down the Channel, they were all far out of hailing distance.

EACH moment the tide crept nearer. Jock saw that within less than five minutes it would reach him, and it was not a pleasant thought.

"If someone doesn't come soon I'm going to be drowned," he remarked aloud, and once more took a despairing glance round the horizon.

He saw nothing, but suddenly he heard, and jerking himself to a sitting position, he stared at the sky. A dark speck was visible against the eastern horizon, and Jock gave a shout of joy as he realised it was a plane. Tim—it must be Tim. Now the only question was whether he would arrive in time.

The plane grew rapidly larger, and the hum rose to the familiar roar. Suddenly the sound ceased as the engine was cut off, and Jock saw the big machine planing down towards the beach. He shouted, and saw a handkerchief wave over the edge of the cockpit, then down it swooped, landing with such precision that it came to rest within a dozen paces of where he lay.

Out sprang Tim. Tim wasted no words, but pulling out his knife, slashed the cords that bound his friend, and dragged him to his feet before he spoke.

"Who did this?" he demanded, and Jock had not known that Tim Bellingham could look or speak so fiercely.

"It was Red," began Jock, but Tim broke in angrily.

"Left you to drown here. I thought you said he was decent."

"He is. He didn't think of the tide. But never mind about that. He's got the emeralds."

"Got the emeralds!" Finch Hanley put his head over the edge of the cockpit and his face showed blank dismay. "Tim here told me you'd hidden them."

"So I had, but he was too cute for me. I thought he was gone, and I'd just got the stones out of the hiding-place when he and his pal swooped down on me. It was all my silly fault," he added bitterly.

"Don't talk rot, Jock," said Tim sharply. "I'll bet anything you weren't to blame. Then he's gone?"

"Yes, he and a man called Mark. They've gone north in their plane."

"How long ago?" demanded Finch Hanley.

"Can't tell exactly, but not more than half an hour."

"What sort of plane?" Finch asked quickly.

"A low-winged monoplane two-seater. Not very big and painted yellow."

"A Dexter, I expect. And you say she went north."

"Across the Channel anyhow, but she was travelling a bit east of north." Finch frowned.

"They won't go back to this Welsh place. The odds are that they'll make for the continent. Hop in, you chaps. There's just a chance we might catch them." Jock and Tim were hardly in their places before Finch was taking off. They put on the phones so that they could talk, and the first thing Jock asked was how Tim had come to find Finch Hanley.

"He was at Bristol Aerodrome. Finch got our message at the police station at Taverton; he managed to get hold of a Moth and flew straight up to Bristol. He meant to come across to Wales but stopped for petrol. He and I came in almost at the same time."

"Jolly lucky," said Jock.

"It would have been better luck if you hadn't come down here, Jock. With the start they've got, I don't see how on earth we're going to catch them. A Dexter's a pretty fast machine. I doubt if this is ten miles an hour faster."

"Suppose they are making for the Continent, as Finch thinks, how long will it take them?" Tim considered a moment.

"It's about five hundred miles from here to Rotterdam and the wind's nor'-nor'-west. It'll take all of five hours." Jock frowned ruefully.

"And they have a start of about sixty miles. No, it doesn't look as if we have much chance of picking them up. Tim, I could kick myself for letting them get those stones."