RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

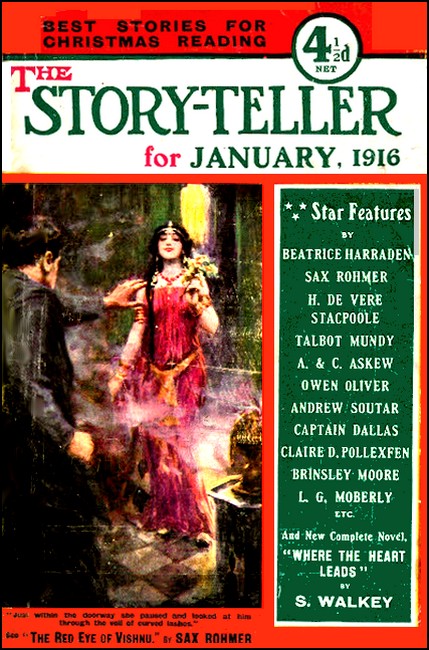

The Story-Teller, January 1916, with "Sam Bagg of the Gabriel Group"

SAM BAGG stood on the highest point of the Thumbmark's upper ridge, staring through his binoculars. He did not see what he looked for; so he put them in their case and stood still, thinking. He had stood on that spot, thinking, most mornings for eighteen years, soaking into himself whatever it is that good men get on the very verge of things.

He was an even-tempered man, but it was not considered wise to approach him when he stood in that place, in just that attitude; and Luther, the imported half-breed missionary, hid himself among the plantains that formed the outer fringe of Bagg's little garden, round the thatched bungalow.

"I wish—oh, I do wish I could tell what will happen!" Luther sighed, watching between the thick stems.

But Bagg was thinking of what had happened, since in that way only can a man judge whether he has earned his salt. He was thinking right back to the beginning—eighteen years ago—when nobody knew very much about the six-and-fifty little islands that make up the Gabriel Group.

Greater and Lesser Gabriel, Inner and Outer Islands, and The Crown are named on the charts—the remainder are shown as black dots; but each one in reality is a red-and-green-and-yellow jewel set in a purple sea, with dazzling white edges to mark the setting. And in the beginning Bill Hill had been king.

Bill Hill did as he chose in those days, and that was always beastly; but Bagg, aged thirty, stepped out of a man-of-war's boat, in a clean white civilian uniform, and the man-of-war hung about in the offing for fourteen days, to give him moral backing. After that Bagg managed without assistance.

Bill Hill—he was called Chief after Bagg came—was the quarter-breed son of a half-breed trader of the bad old days and spoke English fairly well, though he could not sign his name. He lived in a big thatched hut, in a compound with a high palisade round it, at the other end of the island, and cultivated that brand of secretiveness which he thought was privacy.

Bagg's ideas of privacy had been learned at Rugby, where he fagged for a tradesman's son and slept in a dormitory with nineteen other boys. He had some experience of minor consulates and rather more of famine-relief work in Baroda and Guzerat—that is to say, he had a fund of patience to begin with; but the speed with which he induced Bill Hill to have a house built for him out in the open was surprising.

The house was nearly all veranda, wind-swept from three sides; and Bagg lived on the veranda most of the time, in full view of anyone who cared to look, apparently cultivating no privacy at all. But nobody ever seemed able to guess what he was thinking about, whereas Bagg guessed Bill Hill's next move in advance nine times out of ten.

Luther, who was trying hard to do so, could not guess Bagg's thoughts now, though the snuff-and-butter-colored man was supposed to be more intimate with him than any other person on the islands.

"If only one might guess how far Bill Hill dares go!" thought Luther, with fear stamped on his not uninteresting face.

Up on the natural parapet facing the sea Bagg was thinking just that same thing—only with the difference that he did not show it.

"It looks like a show-down," he told himself.

Very early in the game things had settled down into a warfare of sap, pin prick and attrition in which Bagg was the defender and Bill Hill all the other things. Bagg had grown gray-haired and gray-bearded at the game; but Bill Hill, whose revenues under Bagg's supervision were treble what they had been, was fat and had grown ambitious, even to the point of being carried in a hammock when he took the air. He was in a mood by now to take advantage of an opportunity; and to him—and to Bagg—and to Luther—and to the islanders, who had known the real Bill Hill before Bagg came—the opportunity looked ripe, though, of course, each saw it from a different angle.

Bagg quartered the sea again and the horizon with his old-fashioned glass, balancing himself against a gaining wind that stirred the shore—line palms already to a crazy dance. His white drill suit, of the fashion of twenty years ago—for he sends his worn-out suits to Calcutta to be copied—was clean and well pressed; but perhaps his trimmed beard and his finger nails were the best surface indications that he had kept his ideals bright all these years. There are few men who can do that in the islands.

"Dashed if I see a sign!" he told himself. "That's haze over there."

A very ugly, dark-copper-colored native, in a white trade suit of much later pattern than Bagg's, approached him at a dog run along the track Bagg's feet had made on his daily morning walk.

"Breakfus', master!" he said with emphasis, stopping below the ridge of rock. But Bagg did not turn his head; he looked down, on his left, at the whaleboat beached on the sand of a tiny cove, and again seaward, where the waves raced, white-topped, between him and Lesser Gabriel, two miles away, and the sea birds beat up against the wind in hundreds.

Nobody molests the sea birds, because somebody has told the natives that they are loving thoughts, which will turn into devils if they are killed. Luther has tried hard to undermine the superstition and has even asked Bagg's help; and in the evenings, when the low stars swing almost within reach, Bagg has let the more inquisitive natives sit on his steps and talk to him. But they never come when Luther is there, and they are a shy, uncommunicative people. The superstition remains, and Luther cannot tell why, any more than he can guess why Bagg should think so much of sea birds. And Bagg does not care to explain that they remind him of springtime at home.

"Guzzling their fill before the storm," said Bagg aloud; for he knows all the weather signs. "Now—was that smoke, I wonder?"

"Breakfus', master!" said the servant's voice again.

"Has nobody seen the steamer from the North End?"

Bagg asked without troubling to turn his head. The wind blew the words back:

"No, sah. No word dis mawnin', master."

"Get up here and look!" Bagg ordered; for the natives have keen eyes. "Is that smoke on the sky line over there?"

The native stared long, under a flat hand, but shook his head at last.

"No, sah. Steamer not comin' datway. Steamer comin' always by North End, sah. Breakfus' now, master—breakfus,' him ready long time!"

Bagg swept the sea with his glasses again, but the servant protested.

"Send oowhaleboat over Lesser Gabr'el, sah. Bimeby some feller maybe see from dar."

"No," said Bagg.

"Oowhaleboat feller, he all ready by-handy, sah."

"No," repeated Bagg. "It's blowing up for a gale. They'd be swamped in the narrows, without a helmsman! I'll go to breakfast." It is one of Bagg's obsessions that he, and only he, can steer the whaleboat through those waters in a blow, though in the dim, unwritten dawn of history there were war canoes among the Gabriels and have been ever since. But a man is entitled to his own opinion; and at least Bagg has not drowned himself nor anybody else, though from the whaleboat he has explored every nook and cranny of the islands and knows them as some men know other people's business.

Bagg jumped from the parapet and started for his bungalow at a pace that made the native shuffle to keep up, hurrying by without looking up at the flag, which snapped and rippled from its pole on a high mound between the bungalow and the sea. The native, who perhaps was half his age, looked older the moment they were in action, in spite of Bagg's pointed gray beard.

"Who's that?" he asked, stopping when he reached the steps, for he had caught sight of colored cotton between the plantain stems.

"Mishnary feller—Luther, sah."

Bagg continued up the steps and took his place before a table that was white with washed linen and fragrant with coffee, grown as well as ground close by. He ate and slept and wrote his letters all on the veranda.

"Put a chair for him at the table and tell him to come."

The native hurried to obey, while Bagg poured coffee for himself with the manners of a town-bred man.

He sat straight at table. There was no hint about him of the man who has even dealt with beach combers.

In a minute Luther came up the steps, spectacled and nervous, his thin legs seeming yet thinner in red-check cotton trousers. A black cotton shirt under his white jacket was the only attempt at clerical attire, except the sun hat; he removed a huge white topee as he came.

"Take a seat," said Bagg cheerily. "Have breakfast?"

"No; thank you, sir; I have eaten."

"Take a seat then."

Bagg helped himself to fish that would have made an epicure's mouth water; but in the islands one is either hungry or one is not. Luther drew a chair back from the table and a little on one side, and sat on the front edge of it, as though the back part were on fire. He is never quite sure of himself in Bagg's presence. It had been Bagg who wrote to the missionary society for him, and guaranteed him enough to live on; Bagg had ordered the little schoolhouse built, and Bagg had appointed him secretary to the Legislative Council. Yet he admits, even to the natives, that he does not understand Bagg.

For instance, in the matter of geography: Bagg ordered him, when he first came, to teach it to the natives. So, after he had given them their lesson in religion he would tell them about Gabriel Mendoza, the Portuguese, who discovered the islands and gave his name to them. Surely Bagg approved of that, because the information was in the textbook Bagg provided.

Yet the natives insist that when God made the world He left one place in the ocean incomplete, and ordered the Archangel Gabriel to try a hand. So Gabriel, who had sighed for just such an opportunity, wrought his very craftsmanliest; but, being lesser than the Master Craftsman, he pinched the finished jewels a mite too hard when he came to set them in the sea.

Luther is sure that sort of heresy leads straight to hell, and he said so from the first; but Bagg's boat crew took him in the whaleboat and showed him the marks of thumb and forefinger on every one of the islands. Yet, before he began to teach, Luther and Bagg were the only two people thereabout who knew anything concerning either God or Gabriel.

Legends have strange ways of springing up. Once, at breakfast, as it might have been now, Luther asked Bagg to help root out the superstition; but Bagg smiled at him.

"One thing at a time, Luther," he said. "Mustn't go too fast. Be gentle with 'em. There hasn't been a head-hunt since either of us came here—now has there? Besides," he added, "why is that rock called the Thumbmark on the chart if the story isn't true?" And Luther could not answer that.

It was all very disconcerting; so that, though Bagg was invariably kind to him and treated him to many confidences, he never felt at ease on Bagg's veranda. He is not always sure that he is not being laughed at.

"What is it, Luther?" Bagg asked him now between two drinks of coffee; and he fidgeted before he answered.

"A Council meeting, sir. I am sorry to say, sir, it is a meeting of the Legislative Council." He pronounced his English very well, except that he minced it a little. "Bill Hill—I mean the Chief, sir—sent to me this morning and demanded that I call a Council meeting. I replied, of course, that hitherto I have always called meetings at your direction, and not at his."

"Well?" asked Bagg, eating leisurely and not showing any particular emotion, though Luther trembled.

"He came to me, sir, carried in his hammock. Sir, he abused me frightfully! Sir, he called me names—abominable names that I will not repeat to you! Sir, in the end he told me I am secretary by your orders and my job is to call meetings; so, unless I call a meeting, he will act on his own account, without one! I am sorry, sir, to have such a tale to bring to you; but it is the truth."

"He has a perfect right to summon the Council."

"But not to act on his own account unless it is called."

"Call a meeting, then," said Bagg.

"Sir, there never should have been a Council—it is a foolishness!"

But Bagg begged to differ and signified as much by resuming his breakfast. That Council had been his first studied effort to curb Bill Hill's tyranny. It was his child, just as the road round the island was his trade-mark, and the twenty-one police were the beginning of what should be some day.

It had taken him six years of written effort, with three-month intervals between replies, to get the Foreign Office to consent to the Council; but now, even though Bill Hill were to force a vote by means of threats or bribes, Bagg had the veto and could curb him. Bagg nominated half the members, and the Council itself the other half; so that the membership was more or less permanent. And in course of time they had learned a little of self- government.

"Sir," said Luther, too afraid to be diffident as usual, "you do not understand. You are not behind the scenes as I am. Let me explain."

"Glad to listen," Bagg assured him.

"Bill Hill no longer coaxes and persuades—he threatens, and at last the Council members are afraid. There are some who actually want the old times back. Bill Hill says there is no steamer any more—and where is the steamer? What can anybody answer him?"

"Oh, it's late—that's all," said Bagg, more hopefully than Luther quite believed he felt.

"Sir, it is two months overdue!"

"Seven weeks," corrected Bagg. "Broken down, I suppose. Once before it broke down and they sent our mail on a cruiser."

"Yes, sir; but even the cruiser was not ten days overdue. Now this is seven weeks; and Bill Hill says the Protectorate is a thing of the past and you have no authority. He asks where is the promised steamer that should come every month and take away his copra. He says there is nothing with which to pay the police. He says he is rightful king, and you are a—I will not repeat what he says you are, sir."

"Bill Hill's thirsty," said Bagg judicially. "He expected brandy and it has not come; so he's restless."

"Sir, he is worse! He calls this Council meeting expressly to depose you, sir. He has threatened all the members, and he holds their promises—all except mine; he tells me I am secretary and must write your deposition in the minutes, or he will have my head off! Sir, he pointed out the post on which he will have my head spiked!"

"Better do what he says, then," smiled Bagg, still eating and not letting Luther know by any outward sign that he felt disturbed. "Go to the meeting, Luther, and keep the minutes: bring them to me afterward. You'd better remind 'em that nothing's legal without my signature."

"But, sir, if the Council votes as Bill Hill wishes—and how dare it do otherwise?—he will not only succeed in deposing you, he will have you killed!"

"Not while the police are mine!" said Bagg. "Besides, you don't understand, Luther; the Council can't depose me. This is a Protectorate, not a Colony. This isn't British territory. It's protected by Great Britain. The islanders govern themselves under British protection, in accordance with rules mutually agreed on. That's the theory of the thing; and the fact is, Great Britain would back me up in any sort of an argument."

"I only hope it is true, sir. I know Bill Hill does not believe it—and he will act as he believes!"

"Well, run and summon the meeting, Luther. Keep the minutes and report to me. Then, at least, we'll know what the Chief intends."

Far more nervously than he had mounted them, the half-breed missionary descended the steps and hurried down Bagg's stamped coral road in the direction of the four-square Council House some two miles away.

"Boy!" called Bagg, the moment the missionary was out of hearing.

"Sah?"

"Find the sergeant of police and tell him to bring all his men. I want them to drill in front of the flag this morning."

"Breakfus' things, sah—take um away?"

"Find the sergeant of police and deliver my message first."

The native went off at a run and disappeared down a track that led, among plantains and breadfruit and bamboos, to a native village. Bagg picked up his glass and walked to the Thumbmark parapet again, stopping this time to take a long look at the flag.

The spray was beginning to sing over the rock, and when the big sou'westers blow the Thumbmark is a very bursting place of all the big waves in the world, but, as yet, a man could stand on the ridge and be fairly dry; so Bagg stood there and stared at the sky line. Maybe his forearms trembled as he held the glass; but, again, it may have been the wind blowing up his sleeves.

"Looks like it to me!" he said after a while, wiping the object lenses carefully. "It's coming end on and it's thin, so it's hard to tell; but—it looks like it to me."

As a means of passing time before he looked again, he began to watch the birds, which were growing weary of work against a gaining storm or else too gorged to care any more. One after another—presently in fives, tens, twenties—they let themselves be blown down the wind between the islands to shelter in the lee of Greater Gabriel. So an hour passed, and then Bagg yielded to impatience and looked again at the southwest.

"Two masts and two funnels!" he said cheerfully. "Now for Bill Hill! If this doesn't tame him—But it will—it will!"

He jumped from the rock and walked back leisurely to his bungalow, to sit on the top step and turn his glass on the Council House, where the greatest crowd was gathering that he had ever seen together on the island.

"They're all there!" he chuckled. "They'll none of 'em see what's coming!"

The flag snapped in the wind like a whip-crack; and that reminded him! For the first time, he realized that his order to the police had not been obeyed, for nobody was drilling on the stamped dark earth behind the flag mound.

"Boy!" he shouted. "Boy!"

But none answered, and no one came.

"Boy!" he thundered half a dozen times. Then he frowned and lit his pipe. He had shown a bold front to Luther, the half-breed; but he could guess, even better than Luther, how near the native Chief was to getting the upper hand. His pipe went out and he did not relight it. He leaned back against the veranda pole; and his shoulders began to look very tired—more in keeping with the gray hair.

"I rather counted on the police and that one boy," he admitted to himself. "Seems I was wrong! Lord, but it takes time to teach a man how little he is and how little he matters! Think of it—after eighteen years!"

He looked up at the flag which the police had been taught to salute at dawn and dusk.

"But for the flag I could almost wish no help were coming! I shall look small—shan't I?—without one friend after eighteen years, except perhaps Luther! He's not a native; he'll stand by me for his own sake. He'll have to! Yes, the flag wins—law and order wins—help, here in the nick of time; but I lose! I'll apply for a transfer; they'll have to grant it after eighteen years—eighteen years and not a friend on all the islands! If the police and that one boy had stood I'd have been satisfied. I expect I've been too mild. They're used to whips and scorpions. They need a stronger hand over 'em. Well, I did my best. I suppose that's why help's at hand."

There was a feeling creeping over him—a lonely feeling—which had to be battled with, for manhood's sake; so he took up his glass again and began to watch the crowd near the Council House. He saw the fat Bill Hill get into a hammock for the procession. He could see some of his white-skinned constables shepherding the crowd, and Luther walking timidly beside Bill Hill, with the minute book under his arm.

"I must remember to give Luther a good word:" he reminded himself; and as he spoke the procession started.

It was a motley throng—dark skins, cotton suits, shells, feathers—unusually silent but coming swiftly; for the natives can move like smoke blown before the wind. As they drew nearer Bagg thought some of them looked guilty, and he was glad of that. He noticed that his policemen skulked behind.

"It's something if they even feel ashamed!" he thought.

He relighted his pipe now and made himself comfortable on the top step; for, whatever the outcome, he meant that Bill Hill should be met with dignity. He was rather glad that he had found himself a failure.

"I might have died thinking I had really won," he argued. "I'd have gone out proud. I suppose the Lord, who made the wide world, wouldn't laugh at a man; but—my word, I'm glad I knew in time!"

The procession advanced more slowly as it neared him; but it had to approach at last, and from every side his little garden was invaded. Four stalwarts dropped the hammock pole and Bill Hill rolled out, sweating like a pig; the fat brute looked like a Roman senator of the Decline and Fall, with a wreath of flowers awry on his oily hair and his fat legs showing under a baggy white chemise.

"You're deposed!" he said in perfectly good English, pointing at Bagg with a fat forefinger. Bagg smoked on, apparently unperturbed, watched in breathless silence by as many of the crowd as could get near enough. "You're no good!" said Bill Hill. "It's a lie about your ships! This isn't a Protectorate! You're deposed!"

"By whom?" asked Bagg, quite calmly. He wanted to gain seconds. There was a far-away look in his eye that the Chief mistook for terror; so he dared to draw a long stride nearer.

"You're deposed by your Council—our talkers! I was king before you came, and I ran things right. Now I'm king again—your Council says so! It's written in the book. You sign it!"

It seemed to tickle the savage's fancy that Bagg should be made to sign the minutes of his own deposition.

"Take him the book!" he ordered. "Take him the book and show him where to sign."

So Luther, very frightened but not daring to disobey, brought the minute book to Bagg on the top step.

"Show me the entry, Luther," said Bagg, for he did not want the half-breed to look seaward for a moment yet.

"Give him a pen—put it in his hand and make him write!" yelled Bill Hill, turning to explain to the crowd, in their own tongue, what was happening. And as he turned his jaw fell. He seemed suddenly changed to stone. The whole crowd followed his gaze seaward. Bagg smiled.

A cruiser, with two funnels and two masts, and decks all cleared for action, steamed almost casually close inshore!

"I told you a ship would come!" said Bagg.

It occurred to him, then, that it might be well to dip his flag by way of salute, and he started for the pole to do it; but almost the instant he moved the cruiser spoke. From her ensign halyard she broke out the red, white and black of the German Navy, and from a forward port casemate a six-inch gun let rip.

A shell struck the mound on which the British flag was raised, and burst; a second shell burst at the very foot of the pole; a third hit the pole and brought the flag down; and a fourth whined through Bagg's bungalow, bursting in the garden at the rear. Then the cruiser ceased firing for there was nothing more in particular to aim at—the crowd, including Bill Hill and the police, had vanished into thin air.

"Now that's awfully good shooting!" Bagg said stupidly.

There was nothing else to say. His job and his flag and his point of view had all been shot away from under him and he had not even heard a rumor of any war. For a minute he stood and watched the natives, whom he could see now, running down the road for the distant village as though their thatched huts would protect them against gunfire; and it was his sense of humor that brought him to himself. He caught sight of Bill Hill, deserted by the hammock men, waddling down the road as fast as fat legs could be made to move him, shaking impotently angry fists at all the world. Bagg laughed aloud. "There won't be any brandy on the cruiser either," he reflected.

For a minute after that he watched the cruiser, understanding well why her captain did not drop anchor opposite the Thumbmark in such a gale, though he would have dared to do it himself, since he knew the waters.

"He'll anchor in the roadstead," he reflected, for his wits were working again. "Now—what ought I to do first?"

The cruiser's masts went out of sight behind the longshore palms and Bagg's eyes wandered. They lit on the flag, lying tangled in its halyard under half of the pole. He walked to it, unbent it, and rolled it up carefully. So much was obvious.

"What next?" he wondered, looking through his glass in the vague hope of seeing Luther somewhere.

"No; I've got to see this through alone. Well, Luther, you were my friend as long as you dared be. I wonder whether I can do any better than you? Seems to me I've got to bolt too. Difference is, you knew where to run to and I don't. Oh, I know! The papers!"

Rather ashamed of not having thought of that before, he ran to the bungalow and brought out the steel dispatch box that held his official papers, diary and money. Then he filled his pocket with tobacco.

"Is there anything else that matters?" he wondered, stroking his gray beard. "No; nothing else—I can get food anywhere—unless the natives give me up. If they do that I'm done—but I'm not done yet! If the sail and mast are not in the whaleboat, I am, though."

He formed the daring plan of sailing the whaleboat single-handed across to Opposite Point on Lesser Gabriel.

"They won't know yet on the other islands that my authority has been challenged by Bill Hill. Perhaps I can get a following of some sort. At least, I can try. If only I had one man to help me! Imagine—not one man to stand by after eighteen years! I didn't think a fellow could fail so badly as all that!"

With the steel box in one hand he followed the path to his left front, and climbed down steps cut roughly in the coral to the cove below. He was feeling lonelier than ever in his life; but he had barely reached the bottom when eight men rose, like the dead from their graves, to greet him, shaking wet sand from their copper-colored bodies. They so startled him that he nearly dropped the box.

"Why are you here?" he asked. "What do you want?"

A big man—bull-necked and ugly, showing sharp eyeteeth when he grinned—answered him:

"Waiting all along you come!"

Bagg remembered then his orders of the night before that the whaleboat crew should be ready in the morning; he gave that order most nights whether he meant to use the boat or not, since it kept the crew out of mischief. He had no doubt that Bill Hill knew of the order and had taken advantage of it to cut off his retreat by water; his heart fell into his boots. Another man spoke and Bagg felt his fear confirmed.

"Bill Hill—"

But the big man interrupted, waving toward the beached boat with a sinewy, shiny arm.

"Bill Hill no good! Bill Hill one damn—Sam Bagg plenty good! Sea, him big! Come on!"

He snatched the steel box from Bagg's hand and tossed it into the boat, helping Bagg in after it over the stern. Two men took their places on the bow seat and the rest shoved; in a minute they were up to their necks; in another second they were scrambling in over the sides and the boat's nose was headed straight for the cove's mouth and savage water. They all began rowing, taking their time from the bull-necked man at stroke; and, before Bagg knew it, he was standing in the stern, the rolled flag between his knees, steering instinctively.

"Give way, all!" he shouted suddenly. "All to- gether! Swing to it now!"

Eight sets of copper-colored shoulders, alive and lumpy under satin skin, swung evenly to a tune of squealing thwarts and grunting rowlocks. The whaleboat leaped for the narrow entrance and staggered drunkenly as the full force of the gale took her on the starboard shoulder.

"Pull!" roared Bagg, himself by now. "Pull!—Ho! Pull!—Ho!—Pull!—Ho!"

Because they knew him and were used to him they labored at the oars, when an ordinary native crew would have quit and jumped; so that after a while Bagg got the staggering boat stern-on to the sea, and they were able to race along with no more effort than was needed to keep just ahead of the following wave. Bagg still stood up, wearing across the channel as he saw his chance, and wondering why he had not thought of his boat's crew first of all.

"I might at least have offered them a chance!" he argued; he was not in a mood to spare himself if he could only see where he was wrong.

They were rowing more or less in the wake of the cruiser, and Bagg saw her drop anchor opposite Bill Hill's palisade five miles down the strait. He saw a cloud of steam, and judged it must come from her whistle, though the gale prevented him from hearing.

"That'll fetch 'em!" he admitted. "If they keep whistling and don't shoot they'll have every native on the island round them in less than an hour! So much the worse for me, I suppose—the Germans'll demand me and the war canoes'll come after me. What's it all about, I wonder?"

More or less diagonally, and by cautious, small degrees, he wore across the strait to Opposite Point, and there was less than a foot of water in the boat in proof of his coxswainship when he ran in under the promontory's lee. The crew beached the boat and dragged it high out of the water, while Bagg hurried to climb the overhanging rock. There, on the top of it, he sat watching through his glass, and watched, in turn, by the crew below; they did not ask him any questions—he had always told them things if they waited long enough.

"So, eight stood by me!" he was saying to himself. Eight—after eighteen years! That's eight better than none; makes me feel more like a man."

That the cruiser should take on water first and that the natives should answer the whistle and bring the water were things only to be expected; all the ships that call do that. The sweet-water wells on Greater Gabriel, combined with the roadstead, which is sheltered from the prevalent sou'westers, would be ample excuse for seizure of the group by any vagrant navy. Bagg watched the war canoes sneak out, loaded with a cask apiece, and saw the casks hauled up by the cruiser's derricks, to be emptied and sent back for more. He saw fruit go on board, too, and some pigs and fish. All that was easy to understand.

It was obvious why no steamer had come with his mail for seven weeks. It was obvious there must be war; and he supposed the British fleet had somehow failed to get command of the seas and keep it. But he could not guess what the war was about, or what the Germans wanted with this tiny group of islands so early in the game as this must be.

"They can't have been fighting much more than a month," he argued. "Has it got to this already?"

What ought he to do? Should he bury the flag, he wondered—or hoist it somewhere, out of sight of the cruiser? Either course seemed foolish; yet he supposed there was a right course to take.

"I wonder what one of those men one reads about in history would do?" he thought. "I mean one of those chaps who seem to be born to meet emergencies. This is an emergency, all right. Why don't I fit it? I suppose it's because I haven't fitted from the first. If I had handled my job right the natives would all have stood by me—or nearly all; and if I'd been that kind of man I'd have known what to do now. I expect that's it. Well, I did my best anyway," he added, beginning to turn against the lash of his own self-criticism. "Eight stood by me. I won eight!"

He grew tired of watching the cruiser and began to search the island through his glass; so he saw a landing party march toward his bungalow, their white uniforms visible from miles away. He saw them presently surround the little building, and laughed; for he supposed they were shouting to him to come out. He saw men enter it and drag his few possessions into the open. Then he swore aloud, for he saw a man go to windward and set fire to the dry thatch.

"Dogs!" he muttered.

In fifteen minutes the little building that had been his home for eighteen years was gutted to the ground, and its smoke lay like a dirty stain across the island.

"That's wanton!" he swore. "There's no excuse for it! Suppose they are conquerors, have they no decency—no respect? Bill Hill could do no worse!"

He watched them hurry back, marching along his road—the road that had cost him such year-long effort and patient persuasion: the road that stood for the awakening of six-and-fifty islands and the humbling of Bill Hill.

"Damn them!" he swore again, pulling out his pipe and lighting it, to smoke so furiously that the sparks flew in a stream down the wind.

After a while the cruiser began whistling again, and the landing party started running. He could see the steam go R-r-r-r-rrumph!—in short, sharp blasts; and each blast was an added insult, as though the burning of his house were being celebrated. He was too angry to wonder why the landing party hurried so fast on board in one of the cruiser's launches; and he was taken completely by surprise when the cruiser got up anchor and turned down the wind, to steam leisurely away between the islands in the distance.

"Now what in the world—"

He searched as much as he could see of the horizon; and from his point of vantage he was sure that more of it was visible than from the cruiser's masthead. Yet he could see no smoke; and, judging by the cruiser's speed, it did not seem reasonable to suppose she had news of any enemy.

"Just dropped in, burned my house, made trouble, and passed on again! I wonder whether an English cruiser ever did a thing like that? I suppose so—though I'd rather think not. I rather think the man who did it would catch it from home."

He watched the cruiser until her crew were indistinguishable through his glass and then slipped down the rock face on his hands and heel to where his boat's crew waited at the foot.

"Man the boat!" he ordered.

"Goin' where?" asked the big man who pulled the stroke oar.

"Back to the island."

"Bill Hill, him no good!"

"No more am I, my friend; but my place happens to be on the Thumbmark and I'm going back. I'm sorry I came away."

The native did not understand him, for a sentence in English should contain but one verb and one substantive to pass current among the islands; yet there was something in Bagg's attitude that convinced him he had better obey. Bagg did not look aggressive—far from it; he looked like the same Bagg who had explored the islands for days at a time in the whaleboat—and that was the point. Once these men had been Bill Hill's slaves, and they knew the difference between having to do things and doing them because Bagg wished.

"Bill Hill cuttin' t'roat quick!" said the bull-necked man in a last effort to dissuade.

"Very well," Bagg answered. "Man the boat! I would I had not left my post," he added to himself. "At least I can go back to it."

He bent the flag to a boat hook and raised it in the brass tube intended for that purpose in the whaleboat's stern.

"I'll go back the way I came," he said climbing in and seizing the iron tiller. "No—four of you in your places this time—I'm going upwind. Push off—the rest."

The crew sensed his new mood or they would never have won up into the wind at all. His steering and their terrific labor at the white-ash oars got the boat fore-and-aft into it, with less than a foot of water flopping in her, after about two minutes. And then the real fight began. He could have dropped down with the wind to Bill Hill's landing and have dared Bill Hill to do his worst; but he chose that Bill Hill should come to him, and that he should first win back to the post he had deserted. After which he did not see that it mattered what happened.

So the eight oars chopped the waves sea style, deep in the middle. Bagg stood in the stern and the wind shrieked. Inch by inch, up and down hill like a carrousel boat, thumped on her bottom as she rose, and soused as she plunged again, the whaleboat jerked ahead. He steered them out near to midwater, where they had to row or drown; and the eight backs swung in unison, while Bagg looked straight ahead, conscious all the while of the smoke that streamed past him from the ruins of his little house.

"Will it never stop smoking?" he wondered. It seemed like blood to him—like a flow of blood he couldnot stanch. "Pull!" he shouted. "Ho! Pull! Ho! Good men! Good boys! Pull, then! Ho!"

And they gave him the very best of all their strength, because he could praise them while he went to have his throat cut! They obeyed him because he was Sam Bagg; but they did not doubt Bill Hill—for they knew him too, of old.

They had come down the strait in twenty minutes. They fought back to the cove in something like three hours; so that the afternoon was well along and the storm was dying down, as usual toward evening, when Bagg steered into the entrance and the rowing ceased.

"Give way!" he shouted, still standing. "Beach her!"

But they were almost too weary to row through the last hundred yards of comparatively still water; and when the boat's nose touched the sand at last they lay forward on their oars, breathing heavily. Bagg ran by them over the thwarts and jumped ashore, carrying the flag on the boat hook under his arm, and the dispatch box in the other hand.

"Pull her up high and dry!" he ordered, without waiting to see whether they obeyed.

He hurried on to the coral steps. He did not suppose the landing party from the cruiser had left him anything worth recovering, but he wanted to see and to be there. He hurried so fast that he did not see three natives watching him, or that they ran down another path to the cover to speak with his weary crew. But at the top of the steps he turned to shout to the crew to follow him; so he saw all eight of them, with the three who had just come, take to their heels and scamper across the sand, up the other path, and away toward the distant village.

"I thought I had eight!" he said, smiling at himself. "Well, thanks for the ride, you men!"

By a freak of wind-swept fury the fire had left him nothing but his steps—the flight of front steps that were shiny from being sat on—resting on the coral block that had been part of the bungalow's foundation. All of the veranda was burned—only the steps to it remained, leading up to nothing. A little smoke still hurried down the wind, but the fire had died for lack of fuel. In front of the steps lay his one twenty-year-old tweed coat, which he had kept against the day when he should leave the islands; the landing party had not thought it worth looting. He picked it up, laid it on the top step and sat down on it, lest ashes should soil his white drill trousers.

For thirty minutes he sat there, his elbows on his knees and his chin on his hands, exactly as he had sat most evenings for eighteen years. The difference was that now he had a flag on a boat hook laid across his knees, which used to fly from a pole on the mound near by, and that now there was no house behind him. But the sea made the same noise and the islands looked the same. He noticed it.

"I suppose a man gets arrogant," he said aloud; for men who live alone form a habit of talking to themselves. "I tried not to. Lord knows I tried; but I suppose I did. I suppose Rome didn't know she was proud either. That's it! It was pride—and this is the fall. I fall hard and it hurts. I must have been very proud.

"I suppose the Germans have taken these islands and will come back by and by to enforce their rule. I dare say that'll be good for the natives, or otherwise it wouldn't happen to them. I can imagine Bill Hill being penitent—and not so fat nor drunken—under German rule. They'll rule him! They won't call this a Protectorate—it'll be a Colony; and they'll enforce the goose step, among other disagreeable things. All rather different to what it's been!

"I'm sorriest about the Legislative Council; it was child's play, of course, the way it was constituted; but I think the natives would have learned to govern themselves and curb Bill Hill in the end."

He leaned back, forgetting for the moment that there was no veranda post to rest his back against. Then, for a while, he rested his chin on his hands again, watching the sea birds beat up along the strait toward the sunset.

"End of the gale!" he remarked. "They'll roost on Lesser Gabriel and be ready for their breakfast with to-morrow's tide. Happy beggars! They can live on the islands without ruling them or being ruled—no Foreign Office to twist their tails. I hope the Germans will treat them decently."

Staring at the sunset, as he generally had done at the day's end, he followed his train of thought until it brought him back in a circle to the beginning. And then, since thought was a habit with him, he saw his initial error.

"What if the Germans haven't taken the islands? What if they watered and passed on? That seems more likely. I can't believe the British Navy has been licked! I don't believe it! If the Germans had meant to take the islands they would have left my house for their representative to live in. It was a raid—look in, get water, make trouble, and pass on. Well, what then? What happens?"

He whistled softly.

"I would rather the Germans had stayed," he admitted. "I must have done some good in all these years. I've failed, but I must have dropped one or two fertile seeds; the Germans would have cultivated them. Now all I've done—however much or however little—will be undone; for Bill Hill will see to that. Bill Hill will come and cut my throat, as the boatman said."

He unrolled the flag and spread it over his knees like an apron, not realizing what he did. No imaginative man can relish the thought of having his throat cut.

"And after that Bill Hill will run things in his own sweet way for a while, until our navy finds time to readjust things."

He fidgeted with the flag again, rolling and unrolling it, leaving it spread over his knees at last. He made a strange picture, silhouetted on the steps in the light of the setting sun.

"For the islands' sake, I would rather the Germans had stayed," he said at last. "For my own sake, I believe I'm glad they went. I think I'd rather die than have my own crowd find me here—without a friend—after eighteen years. Yes, I've failed. I had better die. What was that about 'All they that take the sword shall perish with the sword'? I believed that when I came—so I did. I can answer to that!

"I've lived here eighteen years without sword or gun—and they were head- hunters when I came here! Yet, I die by the knife! And yet I believe! Yes, I do—I believe! I believe! I've failed, and that's why the knife gets me; but I wish I knew how or in what I have failed. Lord! I have tried!"

Chin on his fists again, he sat and stared into the setting sun that was like to be his last.

"I suppose they'll wait until dark to come and murder me," he mused. "That'd be Bill Hill's way."

It was only by inches, so to speak, he became aware that he was watched; and the lower edge of the sun's red disk had almost touched the sky line before he knew that there were natives on every side of him, watching him, like shadows among the shadows.

"Are you afraid of me?" he asked at last,

"Him coming now!" boomed a strong voice, and he recognized the man who had pulled the stroke oar.

"Strange!" he thought. "Now I wouldn't wait to see Bill Hill murder him!"

But it was Luther who stepped out of a shadow,with natives on each side of him and behind. Suddenly a thousand figures showed themselves in rings all round him, and Luther drew nearer; so that they two were in the middle of a ring.

"Sir!" said Luther, speaking very loud for Luther. "Mr. Bagg!"

"Yes?" said Bagg a little wearily. He was disgusted that Luther should be spokesman for Bill Hill.

"I am spokesman for these natives. They order me to speak in English, very plainly, that there may be no mistake."

"I'm listening," said Bagg, though it was evident that he would rather have done with it all.

"Those Germans came; and they said that the English are beaten; that there are no English ships or cruisers any more; and that these islands are no longer a Protectorate. Their captain—the captain of the cruiser—he explained that these islands are now free, not belonging to anybody but the natives. Bill Hill asked him: 'Do the Germans not take the islands and hoist the German flag?' But he answered: 'No; the Germans cannot be troubled. The islanders are free to govern themselves.' "

"That's what I feared!" groaned Bagg. "Well, Luther, what then?" he asked, for the half-breed had paused and was conferring in whispers with the men who pressed behind.

It seemed to him that Luther was begging mercy for him, though he could not hear what was said. The men behind urged, but Luther seemed to hesitate.

"Well, Luther, what is it?" he asked again.

"They say, sir—these islanders—that they believed the captain of that cruiser; and that, being free, and no longer under British rule, they have done as they chose. I am to say, sir, that they have killed Bill Hill, and that his head is on a spike of his own palisade."

There was dead silence for two minutes. Bagg waited, breathless. The skin of his back was tingling.

"They say, sir, since they have now no Chief and there is no British rule, and they are free, and Bill Hill was bad man, and you are good man, will you be their king?"

Bagg stared; then his head went forward between his hands.

"They ask, sir," continued Luther, "shall they build you a new house here, or will you live in Bill Hill's house at the other end?"

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.