RGL e-Book Cover©

Roy Glashan's Library

Non sibi sed omnibus

Go to Home Page

This work is out of copyright in countries with a copyright

period of 70 years or less, after the year of the author's death.

If it is under copyright in your country of residence,

do not download or redistribute this file.

Original content added by RGL (e.g., introductions, notes,

RGL covers) is proprietary and protected by copyright.

RGL e-Book Cover©

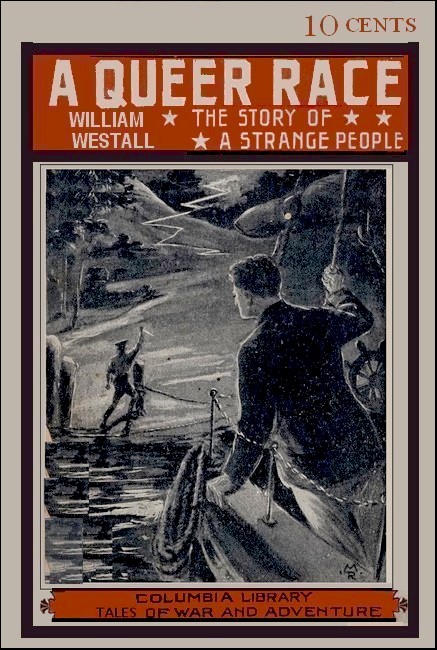

"A Queer Race," Cassell Co., New York, 1887

"A Queer Race," Henry T. Coates & Company, Philadelphia, 1900

"A Queer Race," Street & Smith, New York, 1900

THE heat and burden of the day were over, and I had withdrawn to my own room to write my private letters and think over a few matters which required more consideration than I had yet been able to give them. My nerves were beginning to recover from the shock they had sustained by the loss of the Niobe, and the cyclone at Colon; nevertheless, the outlook was still dark, the claims arising out of these two disasters being exceedingly heavy, and to meet them would tax our resources to the utmost. Another big loss and we should be "in Queer Street." The company would have to suspend payment and go into liquidation.

The worst of it was that, as touching the Niobe, I had rendered myself—in a moral sense—almost personally responsible. A brand-new ship, A1 at Lloyd's, owned by a firm of repute, commanded by a captain of character, and bound only to Havana—a mere summer trip—the risk seemed as light as well could be. I felt myself quite justified in granting a voyage policy of ten thousand pounds on the body of the ship, and covering her cargo for the same amount (without particular average). In fact, I thought that I had done an excellent stroke of business, and when one of the directors, an over-cautious old curmudgeon, with whom I had never been able to get on, suggested the expediency of reinsuring to the extent of a third or a half, I was very much amused, and did not hesitate to tell him so.

Now the laugh was on the other side—the scolding, rather, for at the last Board meeting I had got an awful wigging. All the directors—wondrously wise after the event, as directors are wont to be—could see how imprudently I had acted, and the very men who had chaffed old Slocum for his timidity were now the loudest in blaming my rashness.

Even if the company weathered the storm, it was about even betting that I should lose my berth.

As for the Colon affair, I was in no way blameworthy. Nobody can foresee a cyclone, and both actually and relatively we had been less severely hit than any of our competitors—quite hard enough, however, for our limited capital.

But the Niobe! So far as I could learn, she had not encountered so much as a gale of wind all the way out; yet sprung a leak, and went down in a calm sea off the coast of Cuba; all hands saved, all the cargo lost, except the master's chronometer and sextant!

Queer—very queer! If the owners had been less honorable, and the captain less respectable, I should almost have suspected foul play. Yet even honorable people do strange things; while as for the captain, did not some great authority say that every man has his price? I had reason to believe, too, that both ship and cargo were heavily over-insured, and it was being whispered on 'Change that Barnes & Brandyman would make a deuced good thing by the loss of the Niobe. But what could I do? The Niobe was not the first ship which had foundered in fair weather; and to dispute the claim on grounds that might expose me to an action for slander, and lay the company under suspicion of seeking a pretext to evade payment, would be both foolish and fatal. Everything seemed to be in order; Barnes & Brandyman were an honorable firm, and that day week we must either "pay or burst."

Twenty thousand pounds!

A pleasant lookout! and a nice row there would be when I asked the Board to pass the check! As likely as not old Slocum would insist on suspending payment at once; for we had contingent liabilities in the shape of unclosed risks which might exceed the whole of our uncalled capital.

I had arrived at this point of my musings, when there came a knock at the door, followed by Slocum junior, a cheeky young rascal who, on the strength of being a volunteer and the son of a director, took liberties and gave himself airs.

"Well?" I said, tartly; for he had bounced in without waiting for an invitation.

"There's a man in the office wants to see you, and he refuses either to give his name or state his business; only he says it is very pressing and particular—the business, I mean, not the name."

"What sort of man is he?"

"Seafaring; an Ancient Mariner sort of chap."

"A skipper?"

"Looks like an A. B., boatswain, cockswain, or cook, or something of that sort."

"Oh, I cannot be bothered with able-bodied seamen at this time of day. It is nearly five o'clock, and I have all my letters to write. He must state his business—or stay, he can see me to-morrow morning at ten o'clock."

"All right, I'll tell him. But he's a stupid-looking old beggar; I don't think he will go away."

In two minutes Slocum junior was back again; came in this time without even so much as knocking.

"The Ancient Mariner resolutely and not very respectfully refuses either to state his business or call to-morrow," said the young fellow, jauntily. "Does not care so d—d much whether you see him or not, but it will be to your loss if you don't."

I felt very much disposed to send the Ancient Mariner to the deuce, but curiosity getting the better of dignity, I told Slocum to show him in.

"I thought that would fetch him!" muttered the young jackanapes, as he went out to execute my commission, which he did by going to the door and shouting, "Come in!"

The "Ancient Mariner sort of a chap" came in accordingly. Though evidently in the seafaring profession, there was very little of the conventional sailor about him. He had neither hair on his face nor a quid in his cheeks; neither shivered his timbers nor hitched up his trousers. His manner was quiet and self-possessed, and his voice low (he had certainly not used the coarse expression attributed to him by Slocum); and albeit slightly grizzled, he did not look much above forty. The man had, moreover, a genial, good-humored countenance, the high color of which showed that he had lately voyaged in low latitudes, and his clear, wide-open blue eyes bespoke both honesty and courage.

Slocum junior lingered about the door as if he wanted to take part in the conversation.

"You may go, Mr. Slocum," I said, severely; and muttering something which I did not catch, he went.

"That is right," said the Ancient Mariner; "my business is very private, and"—glancing round—"I hope there's no possibility of anybody listening?"

"None. The door is thick, and fits close, and my desk is a long way from it. Besides, nobody could listen without being seen by all the clerks in the outer office. What can I do for you? Won't you sit down?"

"Thank you kindly. I don't know as you can do much for me; but may be I can do something for you. You are Mr. Sidney Erle, underwriter of the Oriental and Occidental Marine Insurance Company, aren't you?"

"I am. And you?"

"Thomas Bolsover, abled-bodied seaman, late a quartermaster aboard the Niobe."

"Ah!"

"You underwrote the Niobe, didn't you, for a biggish figure?"

"I am sorry to say we did."

"And I am very sorry. But this must not go any further, Mr. Erle. I am only a common seafaring man, late a quartermaster aboard the Niobe, and I don't want to get myself into no trouble."

"I understand, Mr. Bolsover; and you may be sure that I shall do nothing to compromise you. What passes here will go no further without your permission."

"Well, I was going to say as I am sorry to say that the Niobe did not get fair play."

"You mean that she got foul play?"

"I do."

"I feared as much. But is it merely a case of suspicion, or do you know something?"

"I know something. Leastways, if seeing is knowing, I do; but I cannot say as anybody told me anything."

"Seeing is better than hearing in a matter of this sort. What did you see?"

"Well, we had a fine run across, made good weather all the way out, and after touching at St. Thomas', the course was shaped for Cuba. Later on it blew three parts of a gale of wind, but nothing at all to hurt; everything was made snug, and it was over in a few hours. Well, the morning after, I was going below after my spell at the wheel in the second night-watch, when who should I see coming up out of the hold but the captain, with an auger in one hand and a lantern in the other. I said nothing, of course, and though when he saw as I'd seen him he looked a bit flustered, and slunk away to his cabin, I did not think much of it—just then. But when the bo'sun told me next day as we had sprung a leak, I began to put two and two together. Because the ship didn't ought to have sprung a leak; she had done nothing to make her spring a leak. But it was not for me to say anything, and I held my tongue."

"But you kept your weather eye open, I suppose?"

"I tried. Well, she sprung a leak—leastways, they said she did—and the leak gained on us. The carpenter, he could do no good; so the pumps was rigged, and we pumped and pumped for nigh on a week, but the more we pumped the more water she seemed to make, and at last she got so low down that the captain said that, having done our duty by the ship, we must now look to ourselves. So the boats was got out, and the captain, who was the last to leave the deck, came into the dinghy and ordered the others to shove off. They were on the starboard side, we on the port. He had hardly given the order when she gave a list to starboard that nearly bared her keel, lay for a moment on her beam-ends, and then went bodily down. As she heeled over I saw a sight I shall never forget—four big holes in her hull, every one of 'em spouting water."

"Who was in the dinghy besides yourself?"

"The captain, the carpenter, and another A. B."

"Did nobody else see the holes?"

"No. All the other boats was lying off on the starboard side of her."

"After that you went away?"

"Yes; we were not more than fifty miles from the coast of Cuba, and we made land before morning."

"Who do you suppose were the captain's confederates? I mean who, besides himself, do you think was concerned in this vile plot to sink the ship?"

"The carpenter and the first officer."

"And the other sailor who was in the dinghy with you—what has become of him?"

"Alec Tobin? Where he is just now I cannot say; but he shipped at Cuba aboard a homeward-bound ship."

"Well, Mr. Bolsover, I am very much obliged for this information; it is very important. I said I would keep your secret, but I think I shall have to mention the matter to our directors. The information would be of no use to me else. However, that need not trouble you. You shall be protected, whatever comes."

"That is all I want, sir."

"And rewarded. In the meantime, take this"—offering him a sovereign.

"Not for me, thank you, sir. If I was to take money for my information it wouldn't look right. You have only my word for this 'ere, and a man shouldn't take pay for telling the truth."

"You are an honest fellow, Bolsover—as honest as you look. If you won't accept money, I must try to show my gratitude in some other way. It was very good of you to come to me. How did you happen to know my name, might I ask?"

"Oh, I have seen you afore, sir. You maybe remember breakfasting with Captain Peyton aboard the Diana one morning when she lay in the Huskisson Dock?"

"I remember it very well."

"Well, I was one of his crew, and heard him speak of you afterward, and say as you knew Lloyd's Register off by heart; and I heard Captain Deep, of the Niobe, tell the first officer one day as the ship was insured in the Oriental and Occidental, so it seemed sort of natural as I should come to you."

"I am glad you did. Yes, I know Captain Peyton very well. A man of the right sort, he is."

"And a first-rate sailor. He knows his business, he does. You were saying just now as you would like to do something for me. Well, I should like nothing better than to sail with him again; and if you would speak to him, he'd maybe give me a berth as bo'sun or quartermaster. I know a bo'sun's duty as well as any man, sir."

"I'll do that with pleasure, Bolsover, as soon as Captain Peyton comes home; and that won't be long, I think, The Diana is sixty days out from Montevideo, and is pretty sure to be here by the end of the month. You had better leave me your address, and then I can communicate with you about that or the other matter."

I handed him a pen, and he put down his address in a sprawling but sufficiently legible hand. As he bent his arm, his coat-sleeve (which was none of the longest) ran up a little, and bared his wrist, showing a strange device in blue ink: a ship in full sail, above which was tattooed a name, "Santa Anna;" and below, a date, "1774."

I should have liked to ask what it all meant, but as time was going on, and my letters were still to write, I refrained, little thinking how much the device portended nor how strangely the mystery which lay behind it was destined to affect my fortunes.

Then we shook hands, and Bolsover went away and left me to my thoughts.

I WAS right, then; there had been foul play. Captain Deep had committed the crime of barratry, with the connivance, and doubtless at the instance, of the ship's owners, Messrs. Barnes & Brandyman. There are a good many respectable people who would do even worse if they could make twenty thousand pounds thereby, this being the amount which Messrs. Barnes & Brandyman's treachery was likely to bring them; for, as I have already observed, they had insured the Niobe and her cargo largely elsewhere; and, to give the firm their due, they did not do things by halves. They were not the sort of people to commit a felony and run a serious risk for an old song.

But the question that most concerned me was my own course of action. What should I do? It was obvious that I could not bring a charge of barratry against so intensely respectable a firm as Barnes & Brandyman without the most convincing proofs. But the only proof I could adduce was Bolsover's statement, and as he was sure to be flatly contradicted by the captain, the mate, and the carpenter, that would not avail me much, even though I should find and produce Alec Tobin, the other sailor who had seen the holes in the Niobe's hull.

Moreover, no insurance company, above all a company so weak and young as ours, would venture, save on the very strongest grounds; openly to dispute a claim and fight so strong a firm as Barnes & Brandyman; for failure would not only involve discredit, but increase the original loss by the cost of an expensive lawsuit.

All the same, I was determined net to let these people reap the reward of their villainy if I could possibly help it, and after a long cogitation I decided on a plan of campaign which I proceeded to put into execution at the next Board meeting. When the Niobe claim came up for discussion, I quietly observed, to the great amazement of the directors, that I did not think Barnes & Brandyman would insist on its payment. Of course I was overwhelmed by an avalanche of questions, to which I answered that for the moment I must keep my own counsel, but that at the next meeting they should know everything, assuring them that in the meantime they might trust me to neither compromise the company's reputation nor involve it in any further liability. With this they were content, probably because they guessed that I had found something out, and were ready to grasp at any chance, however remote, of keeping the concern on its legs.

I am a pretty good draughtsman, and when I went home in the evening I drew a little sketch, which I made as graphic and as life-like as I could. It represented the hold of a ship, a man boring holes with a big auger, another man behind him holding a lantern; and, hovering above both, a grinning devil, in his hand a well-filled bag, on which was inscribed "£20,000." The first man was Captain Deep, the second Mr. Brandyman, and both, I flatter myself, were rather striking portraits.

The next morning I called at Barnes & Brandyman's office and asked to see Mr. Brandyman; for though not the head of the firm, he was its guiding spirit and presiding genius. A pleasant-spoken, portly, fresh-complexioned, middle-aged gentleman, it seemed the most natural thing in the world that he should wear mutton-chop whiskers and a white waistcoat, sport a big bunch of seals, be an important man in the town, and a shining light at the Rodney Street Chapel (as I understood he was).

He gave me a cordial greeting, and after inquiring, with much seeming interest, as to my own health and that of my mother, he asked how the Oriental and Occidental was getting on.

"As well as can be expected for a new company," I answered, cautiously and vaguely.

"You find the Niobe papers all in order, I hope?"

"Oh, yes; the papers"—emphasis on "papers"—"appear to be quite in order."

"That is all right then. When shall we send round for our check? It is a large amount to be out of Walkers settled yesterday, and the other companies will settle to-day, I believe. All the same, there is no hurry, and if it would be more convenient next week—"

"You can send round for the check whenever you like, Mr. Brandyman, but"—here I paused a moment—"I am by no means sure that you will get it."

"What for, I should like to know?" firing up.

"Look at this, and you will see what for."

And with that I whipped out the sketch and laid it before him.

He looked at it curiously, but when its meaning dawned on his mind (as it did very quickly) his countenance changed as if he had seen a Gorgon's head. His high color gave place to a death-like pallor, the paper dropped from his trembling hand, and there was a hoarse gurgle in his throat which made me fear that he was going to have a fit.

"You seem faint, Mr. Brandyman; drink this, and you will feel better," I said, filling a tumbler of water from a carafe that stood on the table.

"Thank you," he gasped. "'Tis a sudden faintness. It must be the heat of the room, I think. A—a curious sketch this! Where—where did you get it?"

"I drew it, Mr. Brandyman—from information I received."

"Really!"—looking at it again; "I did not think you were so clever, Mr. Erle, and—and—what can I do for you, Mr. Erle?"

"Nothing at all. Only, with your permission, I should just like to give you a hint."

"Of course—certainly—I am sure—yes—what is it?" returned Mr. Brandyman, a little incoherently.

"Well, if I were you, I would not send round for that check. We are a young company, and don't want litigation; but—"

"I will think about it, Mr. Erle. I will speak to my partner, and think about it. And this sketch—you can, perhaps, leave it with me. I should not like—I mean I should like to keep it, if you will let me. It is so very curious."

"By all means. Keep it as a memento of our interview, Mr. Brandyman—and of the Niobe."

And then I bade him good-bye, and returned to the office in the full assurance that the twenty thousand pound check would never be sent for. True, I had no evidence of the barratry worth mentioning—from a legal point of view—but conscience makes cowards of us all. Mr. Brandyman gauged our knowledge of the facts by his own fears. He believed, too, though I had not said so, that we should resist payment of the claim; and as I could well see, he dreaded the scandal of a lawsuit, involving a criminal charge, as much as we dreaded litigation and heavy law expenses.

The Board fully approved of what I had done, and I received many compliments on my smartness. I had saved the Oriental and Occidental from serious danger, and given it a new chance of life; which is another way of saying that I had saved the directors a good deal of money, for as all were shareholders, the failure of the company would have brought them both loss and discredit.

A few days later Tom Bolsover called at the office to tell me (what I knew already) that the Diana had arrived in the Mersey, and to remind me of my promise.

This was quite a work of supererogation on his part. I was not likely to forget either his services or my promise, and I renewed my offer of a handsome reward; but he would accept nothing more valuable than a pound of cavendish tobacco and a box of Havana cigars.

Shortly afterward I saw Captain Peyton and asked him, as a favor to me, to grant Bolsover's request if he possibly could.

"Well," he said, smiling, "I'll do my best. Crazy Tom is a thorough seaman; and, yes—I dare say I can."

"Crazy Tom!" I exclaimed, in surprise. "Why crazy? I never met a saner man in my life."

"Oh, he is sane enough except on one point, and what is more, he's honest. A good many folks call him 'Honest Tom.' It was only on my ship they called him crazy. I expect that is why he left me; and he maybe thinks that if I make him boatswain he will escape being chaffed."

"But why on earth did your people call the poor follow crazy, and what did they chaff him about?"

"Well, he has a fad; tells a yarn about a lost galleon, with a lot of treasure on board, and not only swears it is true, but believes the galleon is still afloat, and that one day or another he'll find her."

"And why shouldn't she be still afloat?"

"Well, seeing that, from his account, it's more than a century since she disappeared, it is not very likely, I think! The idea is perfectly ridiculous and absurd—crazy, in fact," said Captain Peyton, who was a bluff, matter-of-fact north-countryman. "But all this is second-hand. Tom never spoke to me about it in his life, and he has been so unmercifully chaffed that I fancy he does not like to speak about it. I daresay, though, he would tell you the yarn if you have any curiosity on the subject."

"Well, I rather think I should like to hear the story of the lost galleon; for, if not true, it is pretty sure to be interesting, and that's the main point in a story, after all. Se non è vero, è ben trovato, you know."

However, I did not hear Tom's yarn just then, nor until several things had happened which I little expected. Captain Peyton got fresh sailing orders sooner than he anticipated, and made Bolsover happy by engaging him as boatswain; and the latter was so much occupied that he had barely time to call and say "good-bye" the day before the Diana was towed out to sea. I did not see him again for several months, in circumstances which I shall presently relate.

AND now I think it is time I told how it came to pass that, at an age when most young men of my years have only just left college or begun business, I was a professional underwriter, and virtually the manager of the Oriental and Occidental Insurance Company.

My father was a merchant, and for many years a partner in the house of Waterhouse, Watkins, Erle & Co., who traded principally with the West Indies and South America, though being very catholic in their commercial ideas, they would have shipped coals to Newcastle, or warming-pans to Madagascar, if they had been sure about their reimbursement, and could have seen a trifling profit on the venture.

My father, who was the traveling member of the firm, went about a good deal "drumming" for fresh business, and at one period of his life spent several years at Maracaibo, in Venezuela—a fact which accounts for my having been born there. Now, anybody who goes to Maracaibo as surely gets a touch of yellow fever as anybody who stays a winter in London gets a taste of yellow fog. It is a matter of course, and new-comers make their arrangements accordingly. My parents underwent the ordeal the year before I came into the world, which circumstance was supposed to confer on me a complete immunity from this terrible pest of the tropics. I was acclimatized by the mere fact of my birth.

I cannot say that I esteemed the privilege very highly, for I had not the most remote intention of returning to Maracaibo, which from all accounts is a pestiferous, mosquito-haunted pandemonium.

My poor father used to say that whatever else he might leave me, he should at least leave me free from all fear of Yellow Jack.

As it turned out, he left me little else. After his return from foreign climes he settled down in Liverpool, took a big house in Abercrombie Square, entertained largely, and lived expensively. When I was about sixteen, and a pupil at Uppingham School, my father (who had been a free liver) died suddenly of apoplexy, and an investigation of his affairs resulted in the painful discovery that, after payment of his liabilities, the residue of his estate would only provide my mother and myself with an income of something less than two hundred a year. So we had to give up our fine house in Abercrombie Square and go into lodgings, and I left Uppingham and began to earn my own living—literally, for after I was seventeen I did not cost my mother a penny.

The calling I took up was not of my own choosing. Had my father lived a little longer, or left us better off, I should have gone into the army. I did subsequently join the volunteers, and after serving for a while in the artillery, became first lieutenant and then captain in a rifle regiment. In the circumstances, however, I was glad to accept the offer of Mr. Combie, of the firm of Combie, Nelson & Co., ship and insurance brokers, to take me into his office and push me forward, "if I showed myself smart," as he was sure I would.

I justified his confidence, and he kept his word. Although I would much rather have been a soldier, I had sense enough to give my mind to the insurance business, and in a comparatively short time I became familiar with all the intricacies of general average and particular average, the draughting of policies, and the rest; and if I did not, as Captain Peyton had told Tom Bolsover, know Lloyd's Register off by heart, there was not a sea-going ship belonging to the port of Liverpool whose age, classification, and character (which meant, in many instances, the character of her owners) I could not tell without referring to the book.

The partners often consulted me as to the premiums they ought to charge, and the risks which it was prudent for them to take; they gave me a salary which made my mother and myself very comfortable, and had I been patient and waited a few years, I should doubtless have become a member of the firm. But I was ambitions; and when the newly constituted Oriental and Occidental Marine Insurance Company invited me to become their underwriter, I accepted the offer without either hesitation or misgiving.

But cautious Mr. Combie shook his head.

"It's a very fine thing," he said, "for a young man of two-and-twenty to get the writership of a company, and, though I say it that should not say it—to our firm. But you are taking a great responsibility on yourself, and you will need to be very prudent. Fifty thousand pounds is not too much capital for an insurance company, and this is a time of inflation, and the shareholders will expect you to earn them big dividends. Between you and me, I have no great confidence in these new concerns. They are going up like rockets, and some of them, I fear, will come down like sticks. But you are young, and if the Oriental and Occidental does not answer your expectations, you will still have the world before you, and I have always said that you are one of those chaps who will either make a spoon or spoil a horn."

The senior meant kindly, and I thanked him warmly; but I was too much elated by my advancement to give due attention to his warnings, although I had good reason to remember them afterward. My elation did not, however, arise solely, or even chiefly, from professional pride and gratified ambition. The fact is, I had lost my heart to Amy Mainwaring, a charming girl of eighteen, with peach-like cheeks, soft brown eyes, and golden hair; and being as impetuous in love as I was diligent in business, and Amy loving me as much as I loved her, I had made up my mind to marry at the earliest possible moment—that is to say, as soon as the father gave his consent and I could afford to keep a wife. I thought the salary which I was now beginning to earn would enable me to do this easily. But Mr. Mainwaring did not quite see the matter in the same light. He said we were both absurdly young, and however well off I might be, we should be all the better for waiting awhile. Moreover, like Mr. Combie, he had not absolute confidence in the stability of the Oriental and Occidental.

To my pressing entreaties he answered:

"Let us see what a couple of years bring forth. You will be quite young enough then, and the delay will give you a chance of laying something by for a rainy day."

Two years! To Amy and me this seemed an eternity; but as neither of us wanted to defy her father, and he was quite deaf to reason, there was nothing for it but to sigh and submit, and wait with such patience as we might for the fruition of our hopes.

Time went on, and long before the period of probation expired I had to acknowledge that Mr. Mainwaring's caution had more warrant than my confidence. After doing a brilliant business during the first six months of our career, the tide turned, and in a very short time we lost nearly all we had made. For this result—though we had really very ill-luck—I fear that I was in part responsible. I was too keen and sanguine; I did not like to turn money away. I had not Mr. Combie and Mr. Nelson to consult with, and I underwrote risks that I ought to have refused. I had not always the choice, however; for our paid-up capital being small, first-class insurers fought shy of us, fine business went elsewhere, and I had to take my pick among the residue and remainder.

This was the state of things eighteen months after I joined the Oriental and Occidental; and had I not got over the difficulty about the Niobe, it is extremely probable that the company would have smashed or I should have been dismissed. In either event I should have lost my occupation, and in either event Mr. Mainwaring would, I felt sure, have insisted on the rupture of my engagement with his daughter.

Hence my prospects, whether business or matrimonial, were not of the brightest, and Amy and I were often in horribly low spirits. We had thought two years a terrible time, and now I began to fear that I might have to wait for her as long as Jacob had to wait for Rachel. I am bound to say, however, that our gloom was relieved by rather frequent gleams of gaiety and happiness. One does not despair at three-and-twenty.

AFTER my memorable interview with Mr. Brandyman, things took a more favorable turn with the Oriental and Occidental. We had better luck, and I took more care, preferring rather to do a small business than run great risks. Our spirits rose with the shares of the company—mine and Amy's as well as the directors'—and we began to think we were on the highway to prosperity, when a misfortune befell which scattered our hopes to the winds. The Great Northern Bank (like our own, a limited liability concern of recent creation) suspended at a time when we had a heavy balance to credit, and the very day after we had paid away several large checks in settlement of claims. The checks, of course, came back to us, and as we had no means of taking them up, we too had to suspend.

I lost my place, of course—a defunct company has no need of an underwriter; and worse—I had taken a part of my salary in shares, and on these shares there was an unpaid liability which absorbed all my savings. The collapse of the company left me as poor as when I entered Combie & Nelson's office seven years before; and by way of filling up my cup of bitterness to the brim, Mr. Mainwaring informed me (in a letter otherwise very kind and sympathetic) that my engagement with Amy must be considered at an end. He did not forbid me to visit his house, but he said plainly that the seldomer I came the better he should be pleased.

I thought he was hard, but I felt he was right. What was the use of a man being engaged to be married who had no present means of keeping himself, much less a wife? All the same, Amy and I swore eternal constancy, and we vowed that, come weal, come woe, neither of us would ever marry anybody else; and I thought she really meant it—I am sure I did.

This conclusion, however satisfactory as far as it went, did not afford much help toward a solution of the pressing question of the moment: What should I do?—how avoid becoming a burden on my mother? I had asked Mr. Combie to take me back; but my place was filled up, and as a severe financial crisis had just set in there was little chance of my finding a place elsewhere. Firms and banks were falling like ninepins, and men of business looked and talked as if the world were coming to an end. A word to any of them about finding me a situation would have been regarded as an insult to his understanding.

While I was revolving these things in my mind, and wondering what on earth I should do, I received a call from Captain Peyton, who had lately returned from one voyage and was about to start on another. He condoled with me over the failure, and inquired what I "thought of doing," whereupon, as he was an old friend, I told him of my difficulties, and asked his advice.

"What do I think you should do?" he exclaimed, cheerily. "Why, what can you do better than come with me to Montevideo? I mean, of course, as my guest. Make the round trip; you will be back in six months, and by that time business will be better, and you will get as many berths as you want. Young men of your capacity and energy are not too plentiful. What do you say?"

"Yes, with all my heart!" I answered, grasping his hand. "Thanks, a thousand times thanks, Captain Peyton! I have long wanted to make a deep-sea voyage, and after the turmoil and anxiety of the last few weeks the Diana will be a veritable haven of rest. When do you sail?"

"In a fortnight or so."

"All right; I shall be ready. I suppose Bolsover is still with you?"

"Yes, Crazy Tom is our boatswain; and a good one he makes. He will maybe tell you that yarn of his, if you take him when he is in the humor. I tried him one day, but it was no go. He would not bite. I expect he thought I wanted to chaff him."

"Yarn? yarn? Oh, I remember. Something about a galleon, isn't it?"

"Yes; a Spanish treasure-ship lost ages ago. The crazy beggar believes she is still afloat. He is sane on every other point, though. However, you get him to tell you all about it. It is a romantic sort of yarn, I fancy."

"When we get to sea."

"Yes; that will be the time. When we get into the northeast trades, all sails set aloft and alow, and there is not much going on—that is your time for spinning yarns."

Shortly after this I heard a piece of news which completed the tale of my misfortunes, and made me wretched beyond measure. I heard that Amy Mainwaring was engaged to young Kelson! If my mother had not seen it in a letter written by Amy herself to a common friend, I couldn't have believed it; but incredulity was impossible. I was terribly cut up and extremely indignant, and vowed that I would never have anything to do with a woman again—in the way of love.

Two days later we were at sea. The Diana was a fine, full-rigged merchantman, one thousand two hundred tons burden, with an auxiliary screw and a crew of thirty-nine men, miscellaneous cargo of Brummagem ware, Manchester cottons, and Bedford stuffs. She had half a dozen passengers, with all of whom (except, perhaps, a young fellow who was taking a sea voyage for the benefit of his health) time was more plentiful than money. For all that, or perhaps because of that, they were very nice fellows.

We had lots of books among us, and what with reading, talking, smoking, sauntering on deck, playing whist and chess, the days passed swiftly and pleasantly. Now and again we gave a sort of mixed entertainment in the saloon, at which the skipper and as many of the ship's company as could be spared from their duties on deck were present. Two of the passengers could sing comic songs, one fiddled, another recited; I played an accordion and performed a few conjuring tricks, and one way and another we amused our audiences immensely, and won great applause.

I naturally saw a good deal of Tom Bolsover, but in the early part of the voyage the weather was so variable and he so busy that he had little time for conversation, and we exchanged only an occasional word. But when we got into the region of the trades he had more leisure, and going forward one fine morning, I found him silting on a coil of rope, apparently with nothing more important to do than smoke his pipe and stare at the sails.

"I was very sorry to hear of the busting up of that 'ere company," he said, after we had exchanged a few remarks about things in general.

"Yes, you saved us twenty thousand pounds, and I thought that would pull us through; but we lost twice as much by the suspension of our bankers, and then we were up a tree, and no mistake."

"I hope you did not lose much by it, sir?"

"Well, I lost my situation and all my money, and I had a very nice sum laid by."

"All your money! Dear, dear! I am very sorry. But you surely don't mean quite all?"

"Yes, I do. I have very little more left than I stand up in? But what of that? L am young, the world is before me, and when I get back I shall try again. I mean to make my fortune and be somebody yet, Bolsover, before I am very much older."

"Fortune! fortune! If we could only find the Santa Anna we should both make our fortunes right off. There is gold and silver enough on that ship for a hundred fortunes, and big 'uns at that."

"The Santa Anna! What is the Santa Anna, and where is she?"

"I wish I knew," said the old sailor, with a sigh; "I wish I knew. It is what I have been trying to find out these thirty years and more. I'll tell you all about it"—lowering his voice to a confidential whisper—"only don't let the others know—they laugh at me, and say I am crazy. But never mind; let them laugh as wins. I shall find her yet. I don't think I could die without finding her. You won't say anything?"

"Not a word."

"Well," went on the boatswain, after a few pensive pulls at his pipe, "it came about in this way. My father, he was a seafaring man like myself; he has been dead thirty-three years. He'd have been nigh on ninety by this time if he had lived. Well, my father—he was a seafaring man, you'll remember—my father chanced to be at the Azores—a good many people see the Azores, leastways Pico, but not many lands there—but my father did, and stopped a month or two—I don't know what for—and being a matter of sixty years since, it does not much matter. Well, while he was there, he used to go about in a boat, all alone, fishing and looking round—my father was always a curiousish sort of man, and he had an eye like a hawk. Well, one day he was sailing round the island they calls Corvo, very close inshore, when he spies, in a crevice of a cliff—the coast is uncommon rugged—he spies something as didn't look quite like a stone—it was too round and regular like; so he lowers his sail, takes his sculls, and goes and gets it. What do you think it was?"

"I have no idea. A bottle of rum, perhaps."

"No, no, not that," said Torn, with a hurt look, as if I had been jesting with a sacred subject. "It was a tin case. It had been there a matter of forty or fifty years, maybe, washed up by the sea, and never seen by a soul before it was spied by my father. Inside the case was a dokyment as told how, in 1744, a British man-of-war captured the Santa Anna, a Spanish galleon, with millions of money on board."

"Millions! Not millions of pounds?"

"Yes, millions of pounds. She was a big ship, carried forty guns, and must have been a matter of two thousand tons burden. Now, a ship of that size can hold a sight of gold and silver, Mr. Erle."

"Rather. Almost as much as there is in all England, I should say."

"Just so, Mr. Erle," said Bolsover, with glistening eyes. "Suppose she carried no more than one thousand five hundred tons dead weight, and half of it was gold and half silver, that would be a pile of money—make baskets and buckets full of sovereigns and crowns and shillings, to say nothing of sixpences and fourpenny-pieces, wouldn't it, sir?"

"Cartloads! Why, you might give away a few wheelbarrows full without missing them." As the poor fellow was evidently quite cracked on the subject, I thought it best to humor him. "But you surely don't mean to say that the galleon was full—bang up full of gold and silver?"

"Yes, I do; and why not? Doesn't the dokyment say as she was a richly laden treasure-ship? and doesn't it stand to reason that if she was richly laden—mark them words, sir, 'richly laden'—that she must ha' been full."

"Why, yes, it does look so, when you come to think about it," I said, gravely. "The man who finds the Santa Anna will have a grand haul; nothing so sure."

"Won't he!" returned the boatswain, gleefully, in his excitement chucking his pipe into the sea. "Now, look here, Mr. Erle; you said you was poor—as you had lost all the money as you had. Here's a chance for you to get it all back, and twenty thousand times more! Help me to find the Santa Anna, and we will go halves—share and share alike, you know."

"Thank you very much, Bolsover. It's a very handsome offer on your part, and I am awfully obliged; but as yet I must own to being just a little in the dark. Say exactly what it is you want me to do. If it is a ease of diving, I don't think I am the man for you; for, though a fair swimmer, I could never stay long under water, and I don't understand diving-bells."

"No, no, sir; the Santa Anna never foundered; she is on the sea, not under it. You surely don't think, sir, as God A'mighty would let all that money go to Davy Jones' locker? As far as I can make out, all the ship's company died of thirst. When that dokyment was written, they was dreadful short of water; and the ship became a derelict, and went on knocking about all by herself—is, may be, knocking about yet—she was teak-built and very stanch—or otherwise she has run aground on some out-of-the-way island, or drifted into a cove or inlet of the sea. Anyhow, she is worth looking after; and I have always thought as if some gentleman would give me a helpin' hand—somebody with more 'ead and edycation than I have myself—we should be sure to succeed in the end; nay, I am sure we should—I feel it; I know it. Will you help me, Mr. Erle? I cannot tell you how—I am only a common seafaring man; but you are a scholar, with a head like a book. They say as you knows Lloyd's Register by heart, and a man as can learn Lloyd's Register by heart can do anything."

"You are very complimentary, Bolsover, and I am extremely obliged for your good opinion. But you give me credit for a good deal more cleverness than I possess; for, tempting as is an offer of half a shipload of gold and silver, I really don't see what I can do. If I were a skipper and had a ship, or a rich man and owned a yacht, I might possibly help you; but you must see yourself that I cannot go about exploring every island, and inlet, and cove in the world, or keep sailing round it until I spot the derelict Santa Anna, particularly as you don't seem to have the least idea where she was when last heard of."

"There you are mistaken, Mr. Erle, I could a'most put my finger on the very spot. But will you read the dokyment? Then you will know all about it—more than I know myself, for a man as can learn Lloyd's Register—"

"The document! The paper your father found! You surely don't mean to say you have it?" I exclaimed, in surprise; for up to that moment I had thought the boatswain's story pure illusion, and himself as crazy on the point as Peyton said he was.

"Yes, I have it. My father, he gave it me just afore he died. 'Tom,' he says, 'I cannot leave you no money, but I gives you this dokyment. Take care of it, and look out for the Santa Anna, and you'll die a rich man.' Will you read it, Mr. Erle?"

"Certainly. I'll read it with pleasure."

Bolsover rose from the coil of ropes, slipped into the forecastle, and in a few minutes came back, with a smile of satisfaction on his face and a highly polished tin case in his hand.

"Here it is," he said; "you'll find it inside."

"But this is surely not the case your father found at the Azores?"

"No. That was all rusty and much battered. He had hard work to get the dokyment out without spoiling it. He got this case made a-purpose. Nobody has ever read it but him and me. Everybody as I mentioned it to always laughed, and that made me not like showing it. When you have read it, Mr. Erle, you'll tell me what you think. But keep the dokyment to yourself. What's least said is soonest mended, you know; and if you was to mention it to the others they'd only laugh. And now"—looking at his watch—"I must pipe up the second dogwatch."

Promising to observe the utmost discretion, I put the tin case in my pocket, went to the after-part of the ship, lighted a cigar, sat me down on a Southampton chair, and proceeded to carry out Tom's wish by reading the paper which had so much excited his imagination, and was now, in spite of myself, beginning to excite mine.

THE "dokyment," as poor Tom called it, though it seemed to have been carefully used (the leaves being neatly stitched together and protected by a canvas cover), had suffered much from wear and tear, the rust of the original tin case, and the frequent thumbings of its two readers. The ink was faded, the handwriting small and crabbed; the lines were, moreover, so very close together that I found the perusal, or, more correctly, the study of the manuscript by no means easy. Parts of it, in fact, were quite illegible. I had often to infer the meaning of the writer from the context, and there were several passages which I could not make out at all.

No wonder the boatswain wanted a man of "'ead and edycation" to help him. The form of the document was that of a journal, or log; but it was hardly possible that it could be the work of any combatant officer of a warship on active service. The style was too literary and diffuse, and, so to speak, too womanish and devout. The writer, moreover, whose name, as I read on, I found to be "Hare," did not write in the least like a seaman. He could not well have been a passenger; and I had not read far before I found that he was a clergyman and naval chaplain.

The first entry in the diary was probably written at Spithead, and ran thus:

"H. M. S. Hecate,—17th, 1743.

"Left our moorings this day, under sealed orders, so as yet no man on board knows whither we are bound or where we are to cruise. May God bless and prosper our voyage, and protect the dear ones we leave at home!

"19th.—Been very much indisposed the last two days; not very surprising, considering that this is my first voyage, and we have had bad weather. Wind now moderating, but still blowing half a gale.

"20th.—The captain has opened his orders. The Hecate is to sail with all speed across the Atlantic, cruise about the Gulf of Mexico, in the track of homeward-bound Spanish merchantmen, and keep a sharp lookout for treasure-ships. Officers and ship's company highly delighted with the prospect thus opened out of prize-money and hard fighting, these treasure-ships being always either heavily armed or under convoy, or both. To do the Hecate justice, I believe the prospect of hard knocks affords them more pleasure than the hope of reward; and though we carry only forty guns, there is not a sailor on board who is not confident that we are a match for any two Spanish frigates afloat. Our British tars are veritable bull-dogs, and albeit Captain Barnaby does sometimes indulge in profane swearing, the royal navy possesses not a better man nor a braver officer."

Next followed a series of unimportant entries, such as:

"Church parade and divine service."

"In the sick-bay, reading the Bible to Bill Thompson, A.B., who fell yesterday from one of the yard-arms, and lies a-dying, poor fellow."

"Dined with the captain, the second luff, and two of the young gentlemen."

"This day a flying-fish came through my port-hole. One of the ship's boys caught him, and the cook made an excellent dish of him for the gunroom mess. It seemed a shame to kill the creature who sought our hospitality and protection, for he was doubtless escaping from some enemy of the sea or the air."

And so on, and so on. All this did not occupy much space, yet, owing to the reverend gentleman's crabbed fist, the faded ink, and the thumb-marks of the two Bolsovers, it took long to read; and in order not to miss anything, I had made up my mind to read every word that it was possible to decipher.

At length my patience and perseverance received their reward. The diary became gradually less tedious and monotonous. There was a storm in which the Hecate suffered some damage, and the diarist (who does not seem to have been particularly courageous) underwent considerable anxiety and discomfort; and a man fell overboard, and, after an exciting attempt to rescue him, was drowned. Then the Hecate chases a vessel which Captain Barnaby suspects to be a French privateer; but remembering how imperative are his orders to make with all speed his cruising-ground, he resumes his course after following her a few hours. For the same reason he shows a clean pair of heels to a French frigate, greatly to the disgust of his crew, for though she is of superior size, they are quite sure they could have bested her. The chaplain, on the other hand, warmly commends the captain's prudence, observing that "discretion in a commander is to the full as essential as valor."

The region of the gulf reached, everybody is on the watch; there is always a lookout at the mast-head, the officers are continually sweeping the horizon with their glasses, and the men are exercised daily at quarters; for Captain Barnaby, with all his prudence, appears to have been a strict disciplinarian. Being of opinion that he will the better attain his object by remaining outside the Gulf of Mexico than by going inside, he cruises several weeks in the neighborhood of the Bahamas. With little success, however; he captures only two or three vessels of light tonnage and small value, which he takes to Nassau, in New Providence.

Ill-satisfied with this poor result, Barnaby resolves to take a turn in the gulf, and, if he does no good there, to make a dash south, in the hope that he may perchance encounter some homeward-bound galleon from Chili or Peru. So passing through the Straits of Florida, he runs along the northern shores of Cuba, doubles Cape San Antonio, revictuals at Kingston, in Jamaica, and re-enters the South Atlantic between Trinidad and Tobago.

A fortunate move was this in one sense, though, so far as the poor chaplain and a considerable part of the ship's company were concerned, it resulted in dire misfortune.

Ten days after the Hecate left the Caribbean Sea, two

ships were sighted, which the captain and everybody else on board

believed to be the long-sought treasure-ships. But besides being

treasure-ships, they had every appearance of being heavily armed

galleons, and either of them, as touching weight of metal and

strength of crew, was probably more than the frigate's match. All

the same, the

What these measures were, I had some difficulty in making out. I am not a seaman, and Mr. Hare's account, besides being in part illegible, was by no means as clear as it might have been. I will, however, do my best to describe in plain, untechnical language, as any landsman would, the things that came to pass after the commander of the Hecate resolved to engage the galleons single-handed.

The chaplain never gave the frigate's reckoning; but I concluded (in which opinion Bolsover, with whom I afterward discussed the point, concurred) that at this time she was probably a few degrees south of the equator, and not far from the coast of Brazil, sailing west-sou'-west; while the galleons, when first seen, were sailing nor'-east by north. One of them seems to have been a little in advance of the other, and Captain Barnaby's plan was to entice the first—and therefore presumably the faster sailer—to follow him, and so separate the two ships as widely as possible before engaging. To this end he spread all the canvas he could, but slowly and clumsily, in order to give the idea that he was short-handed, and then slipped a spar over the ship's stern as a drag to chock her speed.

The bait took. The galleons, after exchanging signals, hoisted the Spanish flag, whereupon the leading vessel (which, as afterward appeared, was the Santa Anna, the other being the Ruy Blas) gave chase. She was by no means a had sailer, and came on so fast that Captain Barnaby soon found it expedient to haul in the spar and go ahead. But when he had got her fairly away, the course of the Hecate was suddenly changed. Turning on her heel, so to speak, she passed the Santa Anna's bows, delivering a broadside that raked her from stem to stern; and before the Spaniards had time to recover from the confusion into which they were thrown by this unexpected salute, the frigate ran alongside and gave her a second broadside. As Captain Barnaby had given orders to fire high and take careful aim, the two broadsides wrought great havoc among the Santa Anna's rigging. A topmast and several other spars were shot away, the shrouds cut into ribbons, and altogether so much damage was done that she could by no possibility make a move for several hours.

Captain Barnaby next turned his attention to the Ruy Blas, which was gallantly bearing up to her consort's help. The Hecate, having got the weather gauge, was quite prepared, and the two ships were soon at close quarters. The Spaniards stood well to their guns, and a hot fight followed, which, according to Mr. Hare, lasted nearly an hour.

"The scene on deck," wrote the poor chaplain, "was past describing. The half-naked sailors, working the guns, their bodies streaming with perspiration, their faces blackened with powder-smoke, themselves wild with excitement, cheering and yelling like fiends; the officers brandishing their swords and shouting their orders; the roar of artillery; the crash of the Spaniards' balls as they struck our hull; and, above all, the dreadful pools of blood at my feet, and the screams of the poor stricken ones as they fell at their posts or writhed in agony on the deck, thrilled my soul with horror, and, though I prayed fervently for the success of our arms, I feared that God would never bless a victory gained at so terrible a price.

"But the horror of the sights on deck was surpassed by the scene in the cockpit, where, during the engagement, I spent nearly all my time, helping the surgeon, and doing my utmost to solace and console the poor wounded. Their sufferings were heartrending; the sight of their mangled bodies was almost more than I could bear, and I had several times to turn away, or I should have swooned outright.

"Poor Myers, a tiny midshipman of fourteen, a fair-haired and sweet-tempered boy, whom I greatly loved, was brought down, shot through the lungs. The surgeon shook his head. 'He is beyond my skill,' he whispered. 'I must leave him to you.' The poor child looked at me with lack-luster eyes; the pallor of death was on his face; and as I tried to cheer him with hopes of a speedy release from his sufferings, and a happy hereafter, the tears streamed down my cheeks, and I could scarce speak for sobbing. But he seemed to be looking afar off, and gave no heed. 'Mother, mother,' he moaned, 'I am coming home;' and then he died.

"I was turning to the surgeon to tell him that all was over, when we were affrighted and almost thrown off our feet by a terrific explosion, which shook the ship from stem to stern, and made her heel over as if she had been struck by a heavy sea.

"Not knowing what had befallen, but fearing the worst, I ran up the hatchway. The firing had ceased, and consternation was written on every face. I had no need to ask the cause. The Ruy Blas had blown up, and parts of her, which had been projected to a prodigious height, were still falling into the water, where, amid a tangled mass of floating wreckage that darkened the surface of the sea, were struggling a few human forms, sole survivors of the catastrophe.

"As humane as he was brave, Captain Barnaby ordered boats to be lowered. His commands were promptly obeyed, and the men succeeded in rescuing about a score of Spaniards, some of whom were dreadfully hurt. They were taken into the cockpit, and our surgeon had his hands full indeed; but the tale of wounded was now complete, for the captain of the Santa Anna, appalled by the disaster which had overtaken his consort, struck his flag at the first summons. As all had anticipated, she proved to be a rich treasure-ship, being—so ran the report on board the Hecate—laden with little else than gold and silver; and officers and men were soon engaged in computing how much prize-money they were likely to receive. In anticipation they are already rich, but the amount is a matter of conjecture; for a guard has been put over the treasure, and Captain Barnaby declares that he will not have it overhauled until we reach port."

"The Santa Anna's damages have been made good, and a prize crew put on board; and as we have two hundred Spanish prisoners (who might, were they left on the galleon, attempt to retake her), a hundred of them are to be transferred to the Hecate. The captain, who had at first some idea of calling at one of the West India Islands, or at Nassau, has finally decided to make straight for England, and our course has been shaped accordingly."

"Another terrible day, the events of which I can only briefly set down.

"Shortly after six this morning I was roused from a sound sleep by the wardroom steward. 'You had better get up, Mr. Hare,' he said. 'The ship is on fire.'

"Alas! it was only too true.

"After a fight, discipline is always more or less relaxed; the spirit-room had been inadvertently left open, and some unauthorized person, going in with a naked light, accidentally set fire to a can of rum, which, running over the floor, set everything in a blaze.

"The woodwork, desiccated by the heat of the tropics, was as dry as tinder, and the conflagration spread with frightful rapidity. When I readied the deck, although only a few minutes had elapsed since the alarm was given, smoke was coming up the after-hatchway, and the crew, under the direction of the captain, were doing their utmost to put out the fire. Pumps were going; buckets were being passed from hand to hand; the decks were deluged with water, and tons of it poured into the hold.

"But all to little purpose; and after half an hour's strenuous exertion, I heard the captain give an order which showed that he despaired of saving the ship. It was to lower the boats and remove the wounded to the Santa Anna, under the charge of the surgeon and chaplain.

"It was a dreadful task, and caused some of the poor maimed creatures most exquisite pain; but sailors are wonderfully deft and handy, and the order was executed in a much shorter time than might be supposed.

"Yet, short as the time was, the fire had visibly gained ground, and we watched its progress from the deck of the Santa Anna with unspeakable anxiety. But not until the after-part of the ship was wrapped in flames, and her destruction imminent, did the captain give up the attempt to save her, and order the crew to take to the boats and come on board the Santa Anna, which was hove-to at about a cable's length away. He was the last to leave the deck, and ten minutes after he quitted it the Hecate was one mass of flame, a burning fiery furnace, the heat of which we could feel even on the galleon's deck.

"We watched the fire until it burned down to the waters edge and was extinguished by the sea, leaving nothing of the once gallant war-ship behind save a few charred fragments. Then, the wind being fair, orders were given to make sail, and we went on our course, not without hope, despite the omens, of a speedy and happy termination of our eventful cruise.

"Most of the officers and men have lost all their effects in the fire; but, thanks to the thoughtfulness and courage of the boy who waits on me, I have saved a good part of my wardrobe, some writing materials, and nearly all my books."

"The captain informed me this morning that he is very well pleased with the Santa Anna. She is one of the best built ships he ever saw, being constructed of a wood called teak, hard enough and stout enough to last a century. She is also a good sailer, and, with favorable weather and moderate luck, we may, he thinks, reach Portsmouth in about fifty days.

"I sincerely hope so, and pray God he may prove a true prophet: for I am sick of the sea, and so soon as we get home I shall resign my appointment, and seek a less exciting, if a more monotonous, sphere of duty ashore."

"A terrible discovery was made yesterday. We are short of water.

"According to the purser's calculations, made the day after the burning of the Hecate, the supply on board the Santa Anna was amply sufficient for the voyage to England; but it now turns out that several of the casks which he thought were full are quite empty, and we have not more than enough for ten days' consumption. We are already on short allowance, and Captain Barnaby has decided to make for the Bermudas.

"It is very unfortunate this discovery was not made sooner, for at the best we cannot reach New Providence in less than fifteen days, and if we have bad weather or contrary winds—but I will not anticipate evil. We are in the hands of Him whom the winds and waves obey."

"For two days it has blown a hurricane, and we have been driven hundreds of miles out of our course. The allowance of water is reduced to a quart a day for each man for all purposes, and as it is terribly hot, and as our diet consists chiefly of salt pork and hard biscuits, our sufferings are almost past bearing."

"Becalmed. Allowance reduced to a pint."

"Still becalmed. To-day a deputation from the crew waited on the captain, and requested that, in order to economize water, and, perchance, save their lives, the Spanish prisoners should be thrown overboard. This he refused to do, but he ordered the Spaniards' allowance to be reduced to half a pint."

"The Spaniards, maddened by thirst, have attempted to seize the ship. A number of them, who were allowed to walk on deck, secretly released their comrades, and attacked the watch—some with cutlasses obtained I know not how, others with marline-spikes, or whatever else came to hand. The Englishmen at first driven from the deck were speedily re-enforced, and then ensued a frightful struggle in the dark, the Spaniards, utterly reckless of their lives, fighting with the ferocity of despair. But in the end they were overcome, the wounded (and I fear many of the whole) thrown into the sea, and the survivors forced below and put in irons. The captain, himself sorely hurt, had great difficulty in protecting them from the fury of his men, who, if they might have had their way, would not have left a single Spaniard alive."

"Still becalmed. Oh, how gladly would we give this thrice accursed treasure for a few casks of water, or even a few hours' rain!"

"I am sick—I fear, nay, I hope, unto death, for I suffer so horribly from thirst that death would be a happy release. Yesterday two seamen committed suicide, and my dear friend, Captain Barnaby, has died of his wounds and want of water, since, hurt though he was, he nobly refused to take more than his share.

"The command now devolves on Lieutenant Fane. He is a first-rate seaman, and a man of resolute and original character, but he has some strange ideas."

"I write this with difficulty. I am worse. To-morrow I may not be able to write, and as I have no hope of ever seeing England again, I know not what will become of the ship and her crew. I am about to inclose my diary (which contains a narrative of the principal events that have befallen us since the Hecate left England) in a water-tight case and commit it to the waves. It may peradventure be found after many days. . . .

"I beseech any good soul into whose hands these pages may fall to forward them to [illegible] Surrey, England, or to the Secretary of the Admiralty, London.

"On board the galleon Santa Anna,

"February 7, 1744.

"Robert Hare."

"POOR fellow! I wonder what became of him and the others? But why on earth didn't they distill fresh water from sea water?" were the first thoughts that occurred to me after reading the chaplain's narrative.

And then I remembered that the events in question took place in a pre-scientific age; that there was certainly no distilling apparatus on board the Santa Anna, nor, probably, any means of making one large enough to provide for the requirements of two or three hundred, possibly three or four hundred men.

Again, why did not they take to their boats and try to reach land that way instead of waiting helplessly for a wind, with a certainty that if it did not come quickly they must all perish? But I knew not how far they were from the nearest land, for the chaplain never indicated the position of the ship, and seldom gave the date or even the days of the week, so that the length of time which elapsed between the different events set forth in the manuscript was a matter of pure conjecture. It was, moreover, quite possible that the Santa Anna's boats had been smashed by the Hecate's fire, and, in any case, they could not have held the crew and the prisoners and enough provisions and water for a long voyage. I could, however, see nothing to warrant the boatswain's belief that the galleon had become derelict or been cast away. Men can live a long time on a very short allowance of water; the chaplain would naturally be one of the first to succumb, and when the weak ones died off there would be more water for the survivors. Besides, who could say that a breeze had not sprung up, or a heavy shower of rain fallen, the very day after poor Mr. Hare committed his diary to the waves?

I found no opportunity for a few days of speaking to Bolsover again, except in the presence of others. But when the chance came, I returned him his "dokyment," which, in the meanwhile, I had carefully reperused.

"Well, sir," he asked, anxiously, "what do you think?"

Believing that I could do the poor fellow no greater kindness than to cure him of his hallucination, if that were possible, I said that in my opinion there was about as much likelihood of finding the Santa Anna as of finding the lost Atlantis or the philosopher's stone.

"I don't know much about them there," answered Tom, who did not seem greatly impressed by the comparison; "but if you mean as to think there is no likelihood of finding that there galleon, I should be glad to know why you think so, if you would kindly tell me."

"Well, to begin with, there is no proof either that the people on board the Santa Anna died of thirst, as you suppose, or that she became derelict."

"Doesn't that gentleman as wrote the dokyment say as he lay a-dying, and that the men were so punished for want of water that they begun to jump overboard?"

"Two jumped overboard, which I suppose is what the chaplain meant when he said they had committed suicide. But don't you see that every death made a drinker the less? The weak would be the first to go; the strongest, seeing that they would have a fair supply of water, might live for weeks—months, even."

Bolsover's countenance fell; this was a view of the matter that had not occurred to him.

"And how do you know," I went on, "that the Santa Anna did not get to England—or somewhere else—after all? Even in the Doldrums calms don't last forever."

"Well, I think I do know that she didn't get to England," said Tom, quietly. "My father, he thought of that, and he went to a lawyer chap, and pretended as there was somebody on board the Hecate as belonged to him—a great-uncle by his mother's side—and that he wanted to find out what had become of him—a proof of his death—and he got the lawyer chap to write to the Admiralty."

"And did the lawyer chap get an answer?"

"Yes, after waiting a long time, and writing five or six letters—it cost my father a matter of two or three pounds, one way and another. Well, the answer was as the Hecate sailed from Portsmouth on such a date in 1743, revictualed at Nassau, and touched at Jamaica; but as after that nothing more had been heard of her, she must undoubtedly have perished with all on board. Now, doesn't it stand to reason that as nothing has been heard of the Hecate, none of the crew—and all of 'em went on board the Santa Anna, you know—that none of her crew ever got to land?—because the first thing they'd naturally do would be to inform the Admiralty and claim their pay. As for the officers, they would, of course, report themselves, and tell how the Hecate was lost."

"Of course; and the fact that nothing has been heard of her or any of her crew shows, in my opinion, that the fate which the Admiralty think overtook the Hecate overtook the Santa Anna—she perished with all on board, perhaps in a cyclone; or she may have struck on a sunken rock or got burned. Your supposition, Bolsover, that every man-jack of her crew died of thirst, and that she is either afloat or aground with all her treasure on board is—excuse me for saying it—all bosh; and the sooner you get the idea out of your head, the better it will be for your peace of mind."

"I am sorry to hear you say so, Mr. Erle," answered the boatswain, with the air of a man who, though shaken in his opinion, refuses to be convinced. "I am sorry to hear you say so. I cannot argufy like a man of 'ead and edycation, and facts is, may be, against me. Well, I don't care a hang for the facts; and I am as cock-sure as if I saw her this minute as the galleon is a ship yet, or leastways the hull of one, and as I shall set eyes on her afore I die, and carry off as much of that there treasure as will make me as rich as a Jew. If you won't go shares with me, so much the worse for you—that is all as I can say."

Though I saw that it was useless to continue the discussion, I wanted to put one more question.

"Did your father say anything to the Admiralty about the chaplain's statement?" I asked.

"No, he didn't," answered Tom, almost savagely; "he wasn't such a darned fool. He had too much white in his eye, my father had, to put the Admiralty on the track of that there treasure-ship; and as it was nigh on a hundred years after she disappeared, it would have done no manner of good to anybody."

The subject then dropped, and it was not resumed until several rather strange things had come to pass, and Bolsover was in a more placable mood.

WE were now on the verge of the tropics; the weather was perfect, the wind fair, and the sea, covered with small, white-crested waves, chasing each other in wild revelry, superb; the days were delightful; the nights, lighted up by a great round moon, gloriously serene.

The mere fact of living became a pleasure; the noonday's heat was tempered by a balmy breeze, and basking in the sun, and living continually in the open air (I slept on deck), health tingled to my fingers' ends.

It was a pleasure to feel the brave ship surging through the sea, and to watch her great sails as they bellied to the breeze. For days together no sailor had need to go aloft, and one day was so like another that time seemed to stand still. Yet in this very monotony there was an inexplicable charm; it acted as a spiritual anodyne, banishing care, and lulling the mind to sleep. I ceased to think about my future, and Liverpool and business were so remote that they might never have been. Even Amy receded into the far distance, and it was hard to realize that I had once dreamed of marriage and suffered from the pangs of disappointed love.

Why, I often asked myself, had I not been brought up as a soldier or sailor instead of an underwriter? And I wondered how people could dislike the sea. True, there were sometimes storms, and the weather was not always serene; but, after all, storms were few and far between, and I felt sure that the hardships and perils of a seaman's life were grossly exaggerated. Only just before I left Liverpool, I met a man who had crossed the Atlantic half a dozen times without so much as encountering a gale of wind; and it was a notorious fact that A1 hardwood ships, well commanded and manned, and not too deep in the water, seldom came to grief.

I one day talked in this strain to Captain Peyton. I said that I doubted whether a man was in greater danger on board a good ship than inside a good house, and that life on the ocean wave was far pleasanter than life ashore.

"I don't mean, of course, on board a war-ship in time of war," I added, remembering the experience of poor Mr. Hare.

"You think so because we have had such a pleasant voyage and made such good weather, so far," returned the skipper, with a smile, "and I am bound to say that sailing in these latitudes is pleasant. You would think differently, though, if you had ever faced a stiff gale in the North Atlantic, or tried to double Cape Horn in a snow-storm. And I don't agree with you about there being no more danger at sea than ashore. A landsman may live a long life without being once exposed to serious peril. A seaman can hardly make one long voyage without running serious risks. Not to speak of storms and cyclones, sunken rocks and unlighted shores, never a night passes that does not bring the possibility of a collision. The unexpected plays a far more important part at sea than ashore; so much so, that a prosperous, pleasant voyage always makes me a bit uneasy—"

"Like this, for instance?"

"Exactly. Like this. I cannot help thinking it is too good to last, and that Fortune is preparing us some scurvy trick. Who can tell? We may be run down in the night, or have foul weather before morning. All the same, I like my calling. Its very uncertainty is an attraction; a true seaman likes it none the less for its element of danger; and I don't know that I dislike an occasional storm. There is real pleasure in commanding a stout, well-found, well-manned ship in a gale of wind."

"I can well believe it—for a born sailor like you. You are of an adventurous disposition, I think, Captain Peyton."

"I was once. But I am too old now to seek adventures; they must seek me."

"Well, I begin to think I should like a few adventures. My life has been desperately tame so far."

"Has not somebody said that adventures are to the adventurous? You will, maybe, have a bellyful before you get back to Liverpool. Who knows?"

"Ay, who knows? I hope they will be agreeable, though."

"I don't think I could undertake to guarantee that," said the skipper, with a laugh. "Adventures are like babies—you must take them as they come. Step into my cabin and let us have a game of chess and a glass of grog. Everything is going on smoothly, and it is the first officer's watch."

I have already mentioned how we amused ourselves, and that as there was always something going on we never suffered from ennui. We had excitement, too, of a very mild sort, though often rather intense while it lasted; nothing more than exchanging numbers with passing ships, and so ascertaining their names—when they came near enough, which was not always. In point of fact, we had only exchanged numbers with four ships since we sailed; we had, however, passed a good many in the early part of our voyage, and when a vessel was sighted, it was always a matter of speculation and discussion whether she would come within signaling distance or not. The further we got, however, the rarer these meetings became, and for several days past we had not seen a single sail.

So, when, on the morning after my talk with Captain Peyton, one of the mates (a man with wonderfully good eyes), sweeping the horizon with his glass, announced that he could just see the topmast of some ship away to windward, there was quite a flutter of excitement. We passengers had our binoculars out in a moment, though, as our eyes were not quite so keen as those of the second mate, it was some time before we could make out, in the far distance, a couple of sticks that seemed to be emerging from the water, which Bucklow (the mate), a few minutes later, declared to be the masts of a brig.

We went on staring our hardest, and in the end were rewarded by seeing the hull of a large ship rise slowly from "the bosom of the deep."

"A brig under bare poles!" exclaimed Captain Peyton, who was one of the gazers. "No; she has her fore-course and fore-topmast-staysail set. But what on earth is she doing, and where steering?"

I had been asking myself the same questions, for the brig's movements were most eccentric; she wobbled about in every direction, as if she could not make up her mind toward which point of the compass she wanted to sail.

"Are the people aboard of her all asleep, I wonder?" asked the captain. "Run up our number, Mr. Chance" (the third mate). "We shall may be pass near enough to exchange signals."

"Halloo!" shouted Bucklow, the sharp-eyed. "There is something wrong yonder."

"What is it?" asked everybody else, pointing his glass in the same direction as that of the mate.

"The Union Jack upside down."

"A signal of distress! And she does not give her number," said the skipper. "Something very wrong, I should say. Alter the ship's course a point, Mr. Bucklow. We will run under her bows and hail her."

When we were near enough, the captain took his speaking trumpet and hailed. But there came no answer. We could see nobody on deck; there was not even a man at the wheel.

"Queer!" said Captain Peyton, after he had hailed a second and third time. "I must go aboard and see what is up. Clear away the lee-quarter boat, Mr. Chance. Will you go with me, Mr. Erle?" turning to me. "Who knows that this is not the beginning of an adventure?"

"It is an adventure," I answered! "Thanks for the offer. I will go with you gladly."