Eddie is another Polish jew with a harrowing Hollowhoax tale, and miraculous story of survival.

At the "death camps" created by the Germans, Weinstein says jews were lured into gas chambers disguised as showers. But water didn't come out. Nor Zyklon B. Nor diesel engine gas. No, carbon monoxide. Eddie calls them "death showers."

At Treblinka, Weinstein was shot in the right side of his chest, piercing his lung. Eddie didn't go to a hospital or receive any medical treatment. He just hid out in a building at the camp for 3 days, was healed, then went back to work dragging bodies. Another miracle of the Holocaust!

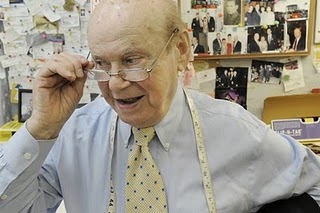

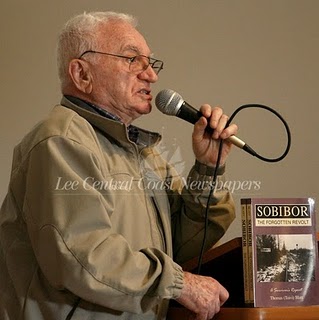

Eddie Weinstein speaks about his experience surviving the Treblinka death camp

Eddie Weinstein speaks about his experience surviving the Treblinka death campSurvivor details escape from Holocaust camp

By Sheryl McCabe

The Acorn

Published: Friday, March 19, 2010

An open class of Perspectives on the Holocaust taught by professor Ann Saltzman presented Holocaust survivor Eddie Weinstein in a section of their curriculum titled “Fighting back: the Jewish Resistance” last Tuesday. Weinstein’s presentation, titled “My Story: An Escape from Treblinka,” taught the class about being Jewish while living in German-occupied Poland.

Saltzman started the class by explaining types of Jewish resistance during World War II. While active resistance, like arms and weapons, could not be used, using sabotage was a popular method to undermine German activities. Saltzman gave examples such as Jewish workers putting straw in bullets so they wouldn’t go off. She also described how Jewish women blew up the crematorium in Auschwitz by putting gun powder in their skirts.

“You are the last generation to hear voices of the Holocaust,” Weinstein said. “My story is about daring to resist and fearing to die.”

He lived in a town 75 miles east of Warsaw with his parents and his brother, Israel. When the Germans invaded Poland, they asked the Jews in his village to create a council, have their own police and own schools. Like many other Jewish people of the time, Weinstein’s village had to wear arm bands bearing the Star of David. “Every few days new orders would be issued against Jews,” Weinstein said.

In August 1940, Weinstein started working on the rail road with 400 other Jewish men. In Feb. 1941, he was sent to build barracks. The Germans were planning to invade Russia. In the spring, the Germans took Weinstein and 50 other men to Warsaw to finish a railroad. He worked the night shift, but decided to escape and walked 60 miles back home.

That June, Russia was invaded. Einsetzgruppen soldiers killed multiple Russians, including Jews, communists and other intellectuals in Russia. Weinstein said that 34,000 Jews were killed in the operation.

Weinstein explained that, by November, his family still had no income because they all worked without pay for Germans. In order to attain food, the family had to sell their items to survive.

The Germans established a ghetto in town where overcrowding was a huge problem. “People slept in attics, basements, hallways, stairs, anywhere,” Weinstein said. They were forbidden to leave the ghetto or they would be executed.

The next year, in 1942, 50 German senior officials met in order to plan a way to systematically murder the Jewish population. Adolf Hitler called it “the final solution to the Jewish question.” The Germans created 6 death camps near railroads. Jewish people would be told that they were needed for work and had to shower in order to disinfect themselves. The shower heads would then release carbon monoxide.

In March of the same year, Weinstein was among 200 young men taken on a train to a concentration camp. They were working on the fields in the snow with little food and no heat. Lung disease, sores and lice were rampant. When Weinstein ran away from the camp, the Jewish police were sent to arrest him. When the police arrived at his house, his mother was arrested instead. His father gave himself in to be arrested for Weinstein and was sent to a concentration camp.

That August, a list of Jews was read by the Jewish Police and taken to the railroad. “As we marched, German soldiers shot at the crowd to speed them up,” Weinstein said.

He talked about how it was a hot day—over 100 degrees—but for 2 days they were given no water. Cattle cars came and all the people were put inside them. Many people died of suffocation and those who jumped off the cars to escape were shot.The train stopped in Treblinka, 62 miles away from Warsaw. “In 2 hours, 20 cattle cars filled with people would die [in Treblinka],” Weinstein said. After 3 and half days with no water, Weinstein and other Jewish men were finally given water. But the scene became chaotic, and the Germans started shooting. Weinstein was shot in the right side of his chest, piercing his lung. His brother hid him between packages in a building in the camp. Weinstein waited 3 days until he went outside. He helped drag bodies and received water as a reward for doing the deed.

He found out that those who stayed alive to maintain the death camp wore red patches on the side of their pants and stuck one on his pants. The sick and wounded were shot then burned in with the garbage. Weinstein recalled that he once went over to the garbage and a group of babies were sitting near the fire. He heard that all the babies were shot and burnt as well. “It’s been more than 67 years, I’ll never forget their beautiful faces,” he said.

One day, the clothing was being put onto a train and Weinstein hid on the train. As the train was moving, he broke open a window, jumped out and went back to his town. No one believed the story of the death shower or camp.Weinstein found his father and went into hiding with him. They hid for 17 months. Two months later, July 29, 1944, the Germans began pulling back from Russia, and the front lines were near the forest Weinstein and his father was hiding in. They left it and the next day, they were liberated from the Russians. Weinstein later joined the Polish army and fought on the front lines for four months to win back Warsaw.

http://www.drewacorn.com/news/survivor-details-escape-from-holocaust-camp-1.1272767