Sacred Texts Taoism Index Previous Next

1. He who knows the part which the Heavenly 2 (in him) plays, and knows(also)that which the Human 2 (in him ought to) play, has reached the perfection (of knowledge). He who knows the part which the Heavenly plays (knows) that it is naturally born with him; he who knows the part which the Human ought to play (proceeds) with the knowledge which he possesses to nourish it in the direction of what he does not (yet) know 3:--to complete one's natural term of years and not come to an untimely end in the middle of his course is the fulness of knowledge. Although it be so, there is an evil (attending this condition). Such knowledge still awaits the confirmation of it as correct; it does so because it is not yet determined 4. How do we know that what

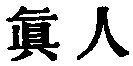

we call the Heavenly (in us) is not the Human? and that what we call the Human is not the Heavenly? There must be the True man 1, and then there is the True knowledge.

2. What is meant by 'the True Man 2?' The True men of old did not reject (the views of) the few; they did not seek to accomplish (their ends) like heroes (before others); they did not lay plans to attain those ends 3. Being such, though they might make mistakes, they had no occasion for repentance; though they might succeed, they had no self-complacency. Being such, they could ascend the loftiest heights without fear; they could pass through water without being made wet by it; they could go into fire without being burnt; so it was

that by their knowledge they ascended to and reached the Tâo 1.

The True men of old did not dream when they slept, had no anxiety when they awoke, and did not care that their food should be pleasant. Their breathing came deep and silently. The breathing of the true man comes (even) from his heels, while men generally breathe (only) from their throats. When men are defeated in argument, their words come from their gullets as if they were vomiting. Where lusts and desires are deep, the springs of the Heavenly are shallow.

The True men of old knew nothing of the love of life or of the hatred of death. Entrance into life occasioned them no joy; the exit from it awakened no resistance. Composedly they went and came. They did not forget what their beginning had been, and they did not inquire into what their end would be. They accepted (their life) and rejoiced in it; they forgot (all fear of death), and returned (to their state before life) 1. Thus there was in them what is called the want of any mind to resist the Tâo, and of all attempts by means of the Human to assist the Heavenly. Such were they who are called the True men.

3. Being such, their minds were free from all thought 2; their demeanour was still and unmoved;

their foreheads beamed simplicity. Whatever coldness came from them was like that of autumn; whatever warmth came from them was like that of spring. Their joy and anger assimilated to what we see in the four seasons. They did in regard to all things what was suitable, and no one could know how far their action would go. Therefore the sagely man might, in his conduct of war, destroy a state without losing the hearts of the people 1; his benefits and favours might extend to a myriad generations without his being a lover of men. Hence he who tries to share his joys with others is not a sagely man; he who manifests affection is not benevolent; he who observes times and seasons (to regulate his conduct) is not a man of wisdom; he to whom profit and injury are not the same is not a superior man; he who acts for the sake of the name of doing so, and loses his (proper) self is not the (right) scholar; and he who throws away his person in a way which is not the true (way) cannot command the service of others. Such men as Hû Pû-kieh, Wû Kwang, Po-î, Shû-khî, the count of Kî, Hsü-yü, Kî Thâ, and Shän-thû Tî, all did service for other men, and sought to secure for them what they desired, not seeking their own pleasure 2.

4. The True men of old presented the aspect of judging others aright, but without being partisans; of feeling their own insufficiency, but being without flattery or cringing. Their peculiarities were natural to them, but they were not obstinately attached to them; their humility was evident, but there was nothing of unreality or display about it. Their placidity and satisfaction had the appearance of joy; their every movement seemed to be a necessity to them. Their accumulated attractiveness drew men's looks to them; their blandness fixed men's attachment to their virtue. They seemed to accommodate themselves to the (manners of their age), but with a certain severity; their haughty indifference was beyond its control. Unceasing seemed their endeavours to keep (their mouths) shut; when they looked down, they had forgotten what they wished to say.

They considered punishments to be the substance (of government, and they never incurred it); ceremonies to be its supporting wings (and they always observed them); wisdom (to indicate) the time (for action, and they always selected it); and virtue to be accordance (with others), and they were all-accordant. Considering punishments to be the substance (of government), yet their generosity appeared in the (manner of their) infliction of death. Considering ceremonies to be its supporting wings, they pursued

by means of them their course in the world. Considering wisdom to indicate the time (for action), they felt it necessary to employ it in (the direction of) affairs. Considering virtue to be accordance (with others), they sought to ascend its height along with all who had feet (to climb it). (Such were they), and yet men really thought that they did what they did by earnest effort 1.

5. In this way they were one and the same in all their likings and dislikings. Where they liked, they were the same; where they did not like, they were the same. In the former case where they liked, they were fellow-workers with the Heavenly (in them); in the latter where they disliked, they were coworkers with the Human in them. The one of these elements (in their nature) did not overcome the other. Such were those who are called the True men.

Death and life are ordained, just as we have the constant succession of night and day;--in both cases from Heaven. Men have no power to do anything in reference to them;--such is the constitution of things 2. There are those who specially regard Heaven 3 as their father, and they still love It (distant as It is) 3;--how much more should they love

That which stands out (Superior and Alone) 1! Some specially regard their ruler as superior to themselves, and will give their bodies to die for him; how much more should they do so for That which is their true (Ruler) 1! When the springs are dried up, the fishes collect together on the land. Than that they should moisten one another there by the damp about them, and keep one another wet by their slime, it would be better for them to forget one another in the rivers and lakes 2. And when men praise Yâo and condemn Kieh, it would be better to forget them both, and seek the renovation of the Tâo.

6. There is the great Mass (of nature);--I find the support of my body on it; my life is spent in toil on it; my old age seeks ease on it; at death I find rest in it;--what makes my life a good makes my death also a good 3. If you hide away a boat in the ravine of a hill, and hide away the hill in a lake, you will say that (the boat) is secure; but at midnight there shall come a strong man and carry it off on his back, while you in the dark know nothing about it. You may hide away anything, whether small or great, in the most suitable place, and yet it shall disappear from it. But if you could hide the world in the world 4, so that there was nowhere to which it could be removed, this would be the grand reality of the

ever-during Thing 1. When the body of man comes from its special mould 2, there is even then occasion for joy; but this body undergoes a myriad transformations, and does not immediately reach its perfection;--does it not thus afford occasion for joys incalculable? Therefore the sagely man enjoys himself in that from which there is no possibility of separation, and by which all things are preserved. He considers early death or old age, his beginning and his ending, all to be good, and in this other men imitate him;--how much more will they do so in regard to That Itself on which all things depend, and from which every transformation arises!

7. This is the Tâo;--there is in It emotion and sincerity, but It does nothing and has no bodily form 3. It may be handed down (by the teacher), but may not be received (by his scholars). It may be apprehended (by the mind), but It cannot be seen. It has Its root and ground (of existence) in Itself. Before there were heaven and earth, from of old, there It was, securely existing. From It came the mysterious existences of spirits, from It the mysterious existence of God 4. It produced heaven; It produced earth. It was before the Thâi-kî 5, and

yet could not be considered high 1; It was below all space, and yet could not be considered deep 1. It was produced before heaven and earth, and yet could not be considered to have existed long 1; It was older than the highest antiquity, and yet could not be considered old 1.

Shih-wei got It 2, and by It adjusted heaven and earth. Fû-hsî got It, and by It penetrated to the mystery of the maternity of the primary matter. The Wei-tâu 3 got It, and from all antiquity has made no eccentric movement. The Sun and Moon got It, and from all antiquity have not intermitted (their bright shining). Khan-pei got It, and by It became lord of Khwän-lun 4. Fäng-î 5 got It, and by It enjoyed himself in the Great River. Kien Wû 6 got It, and by It dwelt on mount Thâi. Hwang-Tî 7 got It, and by It ascended the cloudy sky. Kwan-hsü 8

got It, and by It dwelt in the Dark Palace. Yü-khiang 1 got It, and by It was set on the North Pole. Hsî Wang-mû 2 got It, and by It had her seat in (the palace of) Shâo-kwang. No one knows Its beginning; no one knows Its end. Phäng Zû got It, and lived on from the time of the lord of Yü to that of the Five Chiefs 3. Fû Yüeh 4 got It, and by It became chief minister to Wû-ting 4, (who thus) in a trice became master of the kingdom. (After his death), Fû Yüeh mounted to the eastern portion of the Milky Way, where, riding on Sagittarius and Scorpio, he took his place among the stars.

8. Nan-po Dze-khwei 5, asked Nü Yü 6, saying, 'You are old, Sir, while your complexion is like that of a child;--how is it so?' The reply was, 'I have become acquainted with the Tâo.' The other said, 'Can I learn the Tâo?' Nü Yü said, 'No. How can you? You, Sir, are not the man to do so. There was Pû-liang Î 7 who had the abilities of a sagely man, but not the Tâo, while I had the Tâo, but not the abilities. I wished, however, to teach him, if, peradventure, he might

become the sagely man indeed. If he should not do so, it was easy (I thought) for one possessing the Tâo of the sagely man to communicate it to another possessing his abilities. Accordingly, I proceeded to do so, but with deliberation 1. After three days, he was able to banish from his mind all worldly (matters). This accomplished, I continued my intercourse with him in the same way; and in seven days he was able to banish from his mind all thought of men and things. This accomplished, and my instructions continued, after nine days, he was able to count his life as foreign to himself. This accomplished, his mind was afterwards clear as the morning; and after this he was able to see his own individuality 2. That individuality perceived, he was able to banish all thought of Past or Present. Freed from this, he was able to penetrate to (the truth that there is no difference between) life and death;--(how) the destruction of life is not dying, and the communication of other life is not living. (The Tâo) is a thing which accompanies all other things and meets them, which is present when they are overthrown and when they obtain their completion. Its name is Tranquillity amid all Disturbances, meaning that such Disturbances lead to Its Perfection 3.'

'And how did you, being alone (without any teacher), learn all this?' 'I learned it,' was the reply, 'from the son of Fû-mo 4; he learned it from

the grandson of Lo-sung; he learned it from Shan-ming; he learned it from Nieh-hsü; he, from Hsü-yî; he, from Wû-âo; he, from Hsüan-ming; he, from Zhan-liâo; and he learned it from Î-shih.'

9. Dze-sze 1, Dze-yü 1, Dze-1î 1, and Dze-lâi 1, these four men, were talking together, when some one said, 'Who can suppose the head to be made from nothing, the spine from life, and the rump-bone from death? Who knows how death and birth, living on and disappearing, compose the one body?--I would be friends with him 2.' The four men looked at one another and laughed, but no one seized with his mind the drift of the questions. All, however, were friends together.

Not long after Dze-yü fell ill, and Dze-sze went to inquire for him. 'How great,' said (the sufferer), 'is the Creator 3! That He should have made me the deformed object that I am!' He was a crooked hunchback; his five viscera were squeezed into the

upper part of his body; his chin bent over his navel; his shoulder was higher than his crown; on his crown was an ulcer pointing to the sky; his breath came and went in gasps 1:--yet he was easy in his mind, and made no trouble of his condition. He limped to a well, looked at himself in it, and said, 'Alas that the Creator should have made me the deformed object that I am!' Dze said, 'Do you dislike your condition?' He replied, 'No, why should I dislike it? If He were to transform my left arm into a cock, I should be watching with it the time of the night; if He were to transform my right arm into a cross-bow, I should then be looking for a hsiâo to (bring down and) roast; if He were to transform my rump-bone into a wheel, and my spirit into a horse, I should then be mounting it, and would not change it for another steed. Moreover, when we have got (what we are to do), there is the time (of life) in which to do it; when we lose that (at death), submission (is what is required). When we rest in what the time requires, and manifest that submission, neither joy nor sorrow can find entrance (to the mind) 2. This would be what the ancients called loosing the cord by which (the life) is suspended. But one hung up cannot loose himself;--he is held fast by his bonds 3. And that creatures cannot overcome

Heaven (the inevitable) is a long-acknowledged fact;-why should I hate my condition?'

10. Before long Dze-lâi fell ill, and lay gasping at the point of death, while his wife and children stood around him wailing 1. Dze-lî went to ask for him, and said to them, 'Hush! Get out of the way! Do not disturb him as he is passing through his change.' Then, leaning against the door, he said (to the dying man), 'Great indeed is the Creator! What will He now make you to become? Where will He take you to? Will He make you the liver of a rat, or the arm of an insect 2?

Dze-lâi replied, 'Wherever a parent tells a son to go, east, west, south, or north, he simply follows the command. The Yin and Yang are more to a man than his parents are. If they are hastening my death, and I do not quietly submit to them, I shall be obstinate and rebellious. There is the great Mass (of nature);--I find the support of my body in it; my life is spent in toil on it; my old age seeks ease on it; at death I find rest on it:--what has made my life a good will make my death also a good.

'Here now is a great founder, casting his metal. If the metal were to leap up (in the pot), and say, "I must be made into a (sword like the) Mo-yeh 3."

the great founder would be sure to regard it as uncanny. So, again, when a form is being fashioned in the mould of the womb, if it were to say, "I must become a man; I must become a man," the Creator would be sure to regard it as uncanny. When we once understand that heaven and earth are a great melting-pot, and the Creator a great founder, where can we have to go to that shall not be right for us? We are born as from a quiet sleep, and we die to a calm awaking.'

11. Dze-sang Hû 1, Mäng Dze-fan 1, and Dze-khin Kang 1, these three men, were friends together. (One of them said), 'Who can associate together without any (thought of) such association, or act together without any (evidence of) such co-operation? Who can mount up into the sky and enjoy himself amidst the mists, disporting beyond the utmost limits (of things) 2, and forgetting all others as if this were living, and would have no end?' The three men looked at one another and laughed, not perceiving the drift of the questions; and they continued to associate together as friends.

Suddenly, after a time 3, Dze-sang Hia died. Before he was buried, Confucius heard of the event, and

sent Dze-kung to go and see if he could render any assistance. One of the survivors had composed a ditty, and the other was playing on his lute. Then they sang together in unison,

'Ah! come, Sang Hû ah! come, Sang Hû!

Your being true you've got again,

While we, as men, still here remain

Ohone 1!'

Dze-kung hastened forward to them, and said, 'I venture to ask whether it be according to the rules to be singing thus in the presence of the corpse?' The two men looked at each other, and laughed, saying, 'What does this man know about the idea that underlies (our) rules?' Dze-kung returned to Confucius, and reported to him, saying, 'What sort of men are those? They had made none of the usual preparations 2, and treated the body as a thing foreign to them. They were singing in the presence of the corpse, and there was no change in their countenances. I cannot describe them;--what sort of men are they?' Confucius replied, 'Those men occupy and enjoy themselves in what is outside the (common) ways (of the world), while I occupy and enjoy myself in what lies within those ways. There is no common ground for those of such different ways; and when 1 sent you to condole with those men, I was acting stupidly. They, moreover, make man to be the fellow of the

Creator, and seek their enjoyment in the formless condition of heaven and earth. They consider life to be an appendage attached, an excrescence annexed to them, and death to be a separation of the appendage and a dispersion of the contents of the excrescence. With these views, how should they know wherein death and life are to be found, or what is first and what is last? They borrow different substances, and pretend that the common form of the body is composed of them 1. They dismiss the thought of (its inward constituents like) the liver and gall, and (its outward constituents), the ears and eyes. Again and again they end and they begin, having no knowledge of first principles. They occupy themselves ignorantly and vaguely with what (they say) lies outside the dust and dirt (of the world), and seek their enjoyment in the business of doing nothing. How should they confusedly address themselves to the ceremonies practised by the common people, and exhibit themselves as doing so to the ears and eyes of the multitude?'

Dze-kung said, 'Yes, but why do you, Master, act according to the (common) ways (of the world)?' The reply was, 'I am in this under the condemning sentence of Heaven 2. Nevertheless, I will share

with you (what I have attained to).' Dze-kung rejoined, 'I venture to ask the method which you pursue;' and Confucius said, 'Fishes breed and grow in the water; man developes in the Tâo. Growing in the water, the fishes cleave the pools, and their nourishment is supplied to them. Developing in the Tâo, men do nothing, and the enjoyment of their life is secured. Hence it is said, "Fishes forget one another in the rivers and lakes; men forget one another in the arts of the Tâo."'

Dze-kung said, 'I venture to ask about the man who stands aloof from others 1.' The reply was, 'He stands aloof from other men, but he is in accord with Heaven! Hence it is said, "The small man of Heaven is the superior man among men; the superior man among men is the small man of Heaven 2!"'

12. Yen Hui asked Kung-nî, saying, 'When the mother of Mäng-sun Zhâi 3 died, in all his wailing for her he did not shed a tear; in the core of his heart he felt no distress; during all the mourning rites, he exhibited no sorrow. Without these three things, he (was considered to have) discharged his mourning well;--is it that in the state of Lû one who has not the reality may yet get the reputation of having it? I think the matter very strange.' Kung-nî

said, 'That Mäng-sun carried out (his views) to the utmost. He was advanced in knowledge; but (in this case) it was not possible for him to appear to be negligent (in his ceremonial observances) 1, but he succeeded in being really so to himself Mäng-sun does not know either what purposes life serves, or what death serves; he does not know which should be first sought, and which last 2. If he is to be transformed into something else, he will simply await the transformation which he does not yet know. This is all he does. And moreover, when one is about to undergo his change, how does he know that it has not taken place? And when he is not about to undergo his change, how does he know that it has taken place 3? Take the case of me and you:--are we in a dream from which we have not begun to awake 4?

'Moreover, Mäng-sun presented in his body the appearance of being agitated, but in his mind he was conscious of no loss. The death was to him like the issuing from one's dwelling at dawn, and no (more terrible) reality. He was more awake than others were. When they wailed, he also wailed, having in himself the reason why he did so. And we all have our individuality which makes us what we are as compared together; but how do we know that we

determine in any case correctly that individuality? Moreover you dream that you are a bird, and seem to be soaring to the sky; or that you are a fish, and seem to be diving in the deep. But you do not know whether we that are now speaking are awake or in a dream 1. It is not the meeting with what is pleasurable that produces the smile; it is not the smile suddenly produced that produces the arrangement (of the person). When one rests in what has been arranged, and puts away all thought of the transformation, he is in unity with the mysterious Heaven.'

13. Î-r Dze 2 having gone to see Hsü Yû, the latter said to him, 'What benefit have you received from Yâo?' The reply was, 'Yâo says to me, You must yourself labour at benevolence and righteousness, and be able to tell clearly which is right and which wrong (in conflicting statements).' Hsü Yû rejoined, 'Why then have you come to me? Since Yâo has put on you the brand of his benevolence and righteousness, and cut off your nose with his right and wrong 3, how will you be able to wander in the way of aimless enjoyment, of unregulated contemplation, and the ever-changing forms (of dispute)?' Î-r dze said, 'That may be; but I should

like to skirt along its hedges.' 'But,' said the other, 'it cannot be. Eyes without pupils can see nothing of the beauty of the eyebrows, eyes, and other features; the blind have nothing to do with the green, yellow, and variegated colours of the sacrificial robes.' Î-r dze rejoined, 'Yet, when Wû-kwang 1 lost his beauty, Kü-liang 1 his strength, and Hwang-Tî his wisdom, they all (recovered them) 2 under the moulding (of your system);--how do you know that the Maker will not obliterate the marks of my branding, and supply my dismemberment, so that, again perfect in my form, I may follow you as my teacher?' Hsû Yü said, 'Ah! that cannot yet be known. I will tell you the rudiments. O my Master! O my Master! He gives to all things their blended qualities, and does not count it any righteousness; His favours reach to all generations, and He does not count it any benevolence; He is more ancient than the highest antiquity, and does not count Himself old; He overspreads heaven and supports the earth; He carves and fashions all bodily forms, and does not consider it any act of skill;--this is He in whom I find my enjoyment.'

14. Yen Hui said, 'I am making progress.' Kung-nî replied, 'What do you mean?' 'I have ceased to think of benevolence and righteousness,' was the reply. 'Very well; but that is not enough.'

Another day, Hui again saw Kung-nî, and said, 'I am making progress.' 'What do you mean?'

[paragraph continues] 'I have lost all thought of ceremonies and music.' 'Very well, but that is not enough.,

A third day, Hui again saw (the Master), and said, 'I am making progress.' 'What do you mean?' 'I sit and forget everything 1.' Kung-nî changed countenance, and said, 'What do you mean by saying that you sit and forget (everything)?' Yen Hui replied, 'My connexion with the body and its parts is dissolved; my perceptive organs are discarded. Thus leaving my material form, and bidding farewell to my knowledge, I am become one with the Great Pervader 2 . This I call sitting and forgetting all things.' Kung-nî said, 'One (with that Pervader), you are free from all likings; so transformed, you are become impermanent. You have, indeed, become superior to me! I must ask leave to follow in your steps 3.'

15. Dze-yü 4 and Dze-sang 4 were friends. (Once), when it had rained continuously for ten days, Dze-yü said, 'I fear that Dze-sang may be in distress.' So he wrapped up some rice, and went to give it to him to eat. When he came to Dze-sang's door, there issued from it sounds between singing and wailing;

a lute was struck, and there came the words, 'O Father! O Mother! O Heaven! O Men!' The voice could not sustain itself, and the line was hurriedly pronounced. Dze-yü entered and said, 'Why are you singing, Sir, this line of poetry in such a way?' The other replied, 'I was thinking, and thinking in vain, how it was that I was brought to such extremity. Would my parents have wished me to be so poor? Heaven overspreads all without any partial feeling, and so does Earth sustain all;--would Heaven and Earth make me so poor with any unkindly feeling? I was trying to find out who had done it, and I could not do so. But here I am in this extremity!--it is what was appointed for me 1!'

236:1 See pp. 134-136.

236:2 Both 'Heaven' and 'Man' here are used in the Tâoistic sense;--the meaning which the terms commonly have both with Lao and Kwang.

236:3 The middle member of this sentence is said to be the practical outcome of all that is said in the Book; conducting the student of the Tâo to an unquestioning submission to the experiences in his lot, which are beyond his comprehension, and approaching nearly to what we understand by the Christian virtue of Faith.

236:4 That is, there may be the conflict, to the end of life, between p. 237 faith and fact, so graphically exhibited in the Book of job, and compendiously described in the seventy-third Psalm.

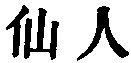

237:1 Here we meet with the True Man, a Master of the Tâo. He is the same as the Perfect Man, the Spirit-like Man, and the Sagely Man (see pp. 127, 128), and the designation is sometimes interchanged in the five paragraphs that follow with 'the Sagely Man.' Mr. Balfour says here that this name 'is used in the esoteric sense,--"partaking of the essence of divinity;"' and he accordingly translates

by 'the divine man.' But he might as well translate any one of the other three names in the same way. The Shwo Wän dictionary defines the name by

by 'the divine man.' But he might as well translate any one of the other three names in the same way. The Shwo Wän dictionary defines the name by

, 'a recluse of the mountain, whose bodily form has been changed, and who ascends to heaven;' but when this account was made, Tâoism had entered into a new phase, different from what it had in the time of our author.

, 'a recluse of the mountain, whose bodily form has been changed, and who ascends to heaven;' but when this account was made, Tâoism had entered into a new phase, different from what it had in the time of our author.

237:2 In this description of 'the True Man,' and in what follows, there is what is grotesque and what is exaggerated (see note on the title of the first Book, p. 127). The most prominent characteristic of him was his perfect comprehension of the Tâo and participation of it.

237:3

has here the sense of

has here the sense of

.

.

238:1 Was not this the state of non-existence? We cannot say of Pantâoism. However we may describe that, the Tâo operates in nature, but is not identical with it.

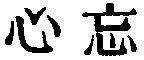

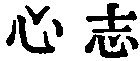

238:2

appears in the common editions as

appears in the common editions as

, which must have got into the text at a very early time. 'The mind forgetting,' or 'free from all thought and purpose,' appears everywhere p. 239 in the Book as a characteristic of the True Man. Not a few critics contend that it was this, and not the Tâo of which it is a quality, that Kwang-dze intended by the 'Master' in the title.

, which must have got into the text at a very early time. 'The mind forgetting,' or 'free from all thought and purpose,' appears everywhere p. 239 in the Book as a characteristic of the True Man. Not a few critics contend that it was this, and not the Tâo of which it is a quality, that Kwang-dze intended by the 'Master' in the title.

239:1 Such antithetic statements are startling, but they are common with both Lâo-dze and our author.

239:2 The seven men mentioned here are all adduced, I must suppose, as instances of good and worthy men, but still inferior to the True Man. Of Hû Pû-kieh all that we are told is that he was 'an ancient worthy.' One account of Wû Kwang is that he p. 240 was of the time of Hwang-Tî, with ears seven inches long; another, that he was of the time of Thang, of the Shang dynasty. Po-î and Shû-khî are known to us from the Analects; and also the count of Khî, whose name, it is said, was Hsü-yü. I can find nothing about Kî Thâ;--his name in Ziâo Hung's text is

Shän-thû Tî was of the Yin dynasty, a contemporary of Thang. He drowned himself in the Ho. Most of these are referred to in other places.

Shän-thû Tî was of the Yin dynasty, a contemporary of Thang. He drowned himself in the Ho. Most of these are referred to in other places.

241:1 All this paragraph is taken as illustrative of the True man's freedom from thought or purpose in his course.

241:2 See note 3 on par. 1, p. 236.

241:3 Love is due to a parent, and so such persons should love Heaven. There is in the text here, I think, an unconscious reference to the earliest time, before the views of the earliest Chinese diverged to Theism and Tâoism. We cannot translate the

here.

here.

242:1 The great and most honoured Master,--the Tâo.

242:2 This sentence contrasts the cramping effect on the mind of Confucianism with the freedom given by the doctrine of the Tâo.

242:3 The Tâo does this. The whole paragraph is an amplification of the view given in the preceding note.

242:4 The Tâo cannot be taken away. It is with its possessor, an ever-during thing.'

243:1 See p. 242, note 4.

243:2 Adopting the reading of

for

for

, supplied by Hwâi-nan dze.

, supplied by Hwâi-nan dze.

243:3 Our author has done with 'the True Man,' and now brings in the Tâo itself as his subject. Compare the predicates of It here with Bk. II, par. 2. But there are other, and perhaps higher, things said of it here.

243:4 Men at a very early time came to believe in the existence of their spirits after death, and in the existence of a Supreme Ruler or God. It vas to the Tâo that those concepts were owing.

243:5 The primal ether out of which all things were fashioned by the interaction of the Yin and Yang. This was something like the p. 244 current idea of protoplasm; but while protoplasm lies down in the lower parts of the earth, the Thâi-kî was imagined to be in the higher regions of space.

244:1 The Tâo is independent both of space and time.

244:2 A prehistoric sovereign.

244:3 A name for the constellation of the Great Bear.

244:4 Name of the spirit of the Khwan-lun mountains in Thibet, the fairy-land of Tâoist writers, very much in Tâoism what mount Sumêru is in Buddhism.

244:5 The spirit presiding over the Yellow River;--see Mayers's Manual, pp. 54, 55.

244:6 Appears here as the spirit of mount Thâi, the great eastern mountain; we met with him in I, 5, but simply as one of Kwang-dze's fictitious personages.

244:7 Appears before in Bk. II; the first of Sze-mâ Khien's 'Five Tîs;' no doubt a very early sovereign, to whom many important discoveries and inventions are ascribed; is placed by many at the head of Tâoism itself.

244:8 The second of the 'Five Tîs;' a grandson of Hwang-Tî. I do not know what to say of his 'Dark Palace.'

245:1 The Spirit of the Northern regions, with a man's face, and a bird's body, &c.

245:2 A queen of the Genii on mount Khwän-lun. See Mayers's Manual, pp. 178, 179.

245:3 Phäng Zû has been before us in Bk. I. Shun is intended by 'the Lord of Yü.' The five Chiefs;--see Mencius, VI, ii, 7.

245:4 See the Shû, IV, viii; but we have nothing there of course about the Milky Way and the stars.--This passage certainly lessens our confidence in Kwang-dze's statements.

245:5 Perhaps the same as Nan-po Dze-khî in Bk. IV, par. 7.

245:6 Must have been a great Tâoist. Nothing more can be said of him or her.

245:7 Only mentioned here.

246:1 So the

is explained.

is explained.

246:2 Standing by himself, as it were face to face with the Tâo.

246:3 Amid all changes, in life and death, the possessor of the Tâo, has peace.

246:4 Meaning writings; literally, 'the son of the assisting pigment.' p. 247 We are not to suppose that by this and the other names that follow individuals are intended. Kwang-dze seems to have wished to give, in his own fashion, some notion of the genesis of the idea of the Tâo from the first speculations about the origin of things.

247:1 We need not suppose that these are the names of real men. They are brought on the stage by our author to serve his purpose. Hwâi-nan makes the name of the first to have been Dze-shui (

).

).

247:2 Compare the same representation in Bk. XXIII, par. 10. Kû Teh-kih says on it here, 'The head, the spine, the rump-bone mean simply the head and tail, the beginning and end. All things begin from nothing and end in nothing. Their birth and their death are only the creations of our thought, the going and coming of the primary ether. When we have penetrated to the non-reality of life and death, what remains of the body of so many feet?'

247:3 The 'Creator' or 'Maker' (

) is the Tâo.

) is the Tâo.

248:1 Compare this description of Dze-yü's deformity with that of the poor Shû, in IV, 8.

248:2 Such is the submission to one's lot produced by the teaching of Tâoism.

248:3 Compare the same phraseology in III, par. 4, near the end. In correcting Mr. Balfour's mistranslation of the text, Mr. Giles himself falls into a mistranslation through not observing that the

p. 249 is passive, having the

p. 249 is passive, having the

that precedes as its subject (observe the force of the

that precedes as its subject (observe the force of the

after

after

in the best editions), and not active, or governing the

in the best editions), and not active, or governing the

that follows.

that follows.

249:1 Compare the account of the scene at Lâo-dze's death, in III, par. 4.

249:2 Here comes in the belief in transformation.

249:3 The name of a famous sword, made for Ho-lü, the king of p. 250 Wû (B. C. 514-494). See the account of the forging of it in the

, ch. 74. The mention of it would seem to indicate that Dze-lâi and the other three men were of the time of Confucius.

, ch. 74. The mention of it would seem to indicate that Dze-lâi and the other three men were of the time of Confucius.

250:1 These three men were undoubtedly of the time of Confucius, and some would identify them with the Dze-sang Po-dze of Ana. VI, i, Mäng Kih-fan of VI, 13, and the Lâo of IX, vi, 4. This is very unlikely. They were Tâoists.

250:2 Or, 'without end.'

250:3 Or, 'Some time went by silently, and.'

251:1 In accordance with the ancient and modern practice in China of calling the dead back. But these were doing so in a song to the lute.

251:2 Or, 'they do not regulate their doings (in the usual way).'

252:1 The idea that the body is composed of the elements of earth, wind or air, fire, and water.

252:2 A strange description of himself by the sage. Literally, 'I am (one of) the people killed and exposed to public view by Heaven;' referring, perhaps, to the description of a living man as 'suspended by a string from God.' Confucius was content to accept his life, and used it in pursuing the path of duty, according to his conception of it, without aiming at the transcendental method of the Tâoists. I can attach no other or better meaning to the expression.

253:1 Misled by the text of Hsüang Ying, Mr. Balfour here reads

instead of

instead of

.

.

253:2 Here, however, he aptly compares with the language of Christ in Matthew vii. 28.--Kwang-dze seems to make Confucius praise the system of Tâoism as better than his own!

253:3 Must have been a member of the Ming or Ming-sun family of Lû, to a branch of which Mencius belonged.

254:1 The people set such store by the mourning rites, that Mäng-sun felt he must present the appearance of observing them. This would seem to show that Tâoism arose after the earlier views of the Chinese.

254:2 I adopt here, with many of the critics, the reading of

instead of the more common

instead of the more common

.

.

254:3 This is to me very obscure.

254:4 Are such dreams possible? See what I have said on II, par. 9.

255:1 This also is obscure; but Confucius is again made to praise the Tâoistic system.

255:2 Î-r is said by Lî Î to have been 'a worthy scholar;' but Î-r is an old name for the swallow, and there is a legend of a being of this name appearing to king Mia, and then flying away as a swallow;--see the Khang-hsî Thesaurus under

. The personage is entirely fabulous.

. The personage is entirely fabulous.

255:3 Dismembered or disfigured you.

256:1 Names of parties, of whom we know nothing. It is implied, we must suppose, that they had suffered as is said by their own inadvertence.

256:2 We must suppose that they had done so.

257:1 'I sit and forget;'--generally thus supplemented (

). Hui proceeds to set forth the meaning he himself attached to the phrase.

). Hui proceeds to set forth the meaning he himself attached to the phrase.

257:2 Another denomination, I think, of the Tâo. The

is also explained as meaning, 'the great void in which there is no obstruction (

is also explained as meaning, 'the great void in which there is no obstruction (

).

).

257:3 Here is another testimony, adduced by our author, of Confucius's appreciation of Tâoism; to which the sage would, no doubt, have taken exception.

257:4 Two of the men in pars. 9, 10.

258:1 Here is the highest issue of Tâoism;--unquestioning submission to what is beyond our knowledge and control.