Sacred Texts Taoism Index Previous Next

1. Notwithstanding the greatness of heaven and earth, their transforming power proceeds from one lathe; notwithstanding the number of the myriad things, the government of them is one and the same; notwithstanding the multitude of mankind, the lord of them is their (one) ruler 2. The ruler's (course) should proceed from the qualities (of the Tâo) and be perfected by Heaven 3, when it is so, it is called 'Mysterious and Sublime.' The ancients ruled the world by doing nothing;-simply by this attribute of Heaven 4.

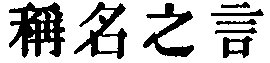

If we look at their words 5 in the light of the Tâo, (we see that) the appellation for the ruler of the

world 1 was correctly assigned; if we look in the same light at the distinctions which they instituted, (we see that) the separation of ruler and ministers was right; if we look at the abilities which they called forth in the same light, (we see that the duties of) all the offices were well performed; and if we look generally in the same way at all things, (we see that) their response (to this rule) was complete 2. Therefore that which pervades (the action of) Heaven and Earth is (this one) attribute; that which operates in all things is (this one) course; that by which their superiors govern the people is the business (of the various departments); and that by which aptitude is given to ability is skill. The skill was manifested in all the (departments of) business; those departments were all administered in righteousness; the righteousness was (the outflow of) the natural virtue; the virtue was manifested according to the Tâo; and the Tâo was according to (the pattern of) Heaven.

Hence it is said 3, 'The ancients who had the nourishment of the world wished for nothing and the world had enough; they did nothing and all things were transformed; their stillness was abysmal, and the people were all composed.' The Record says 4, 'When the one (Tâo) pervades it, all business

is completed. When the mind gets to be free from all aim, even the Spirits submit.'

2. The Master said 1, 'It is the Tâo that overspreads and sustains all things. How great It is in Its overflowing influence! The Superior man ought by all means to remove from his mind (all that is contrary to It). Acting without action is what is called Heaven(-like). Speech coming forth of itself is what is called (a mark of) the (true) Virtue. Loving men and benefiting things is what is called Benevolence. Seeing wherein things that are different yet agree is what is called being Great. Conduct free from the ambition of being distinguished above others is what is called being Generous. The possession in himself of a myriad points of difference is what is called being Rich. Therefore to hold fast the natural attributes is what is called the Guiding Line (of government) 2; the perfecting of those attributes is what is called its Establishment; accordance with the Tâo is what is called being Complete; and not allowing anything external to affect the will is what is called being Perfect. When the Superior man understands these ten things, he keeps all matters as it were sheathed in himself, showing the greatness of his mind; and through the outflow of his doings, all things move (and come to him). Being such, he lets the gold he hid in the hill, and the pearls in the deep; he considers not

property or money to be any gain; he keeps aloof from riches and honours; he rejoices not in long life, and grieves not for early death; he does not account prosperity a glory, nor is ashamed of indigence; he would not grasp at the gain of the whole world to be held as his own private portion; he would not desire to rule over the whole world as his own private distinction. His distinction is in understanding that all things belong to the one treasury, and that death and life should be viewed in the same way 1.'

3. The Master said, 'How still and deep is the place where the Tâo resides! How limpid is its purity! Metal and stone without It would give forth no sound. They have indeed the (power of) sound (in them), but if they be not struck, they do not emit it. Who can determine (the qualities that are in) all things?

'The man of kingly qualities holds on his way unoccupied, and is ashamed to busy himself with (the conduct of) affairs. He establishes himself in (what is) the root and source (of his capacity), and his wisdom grows to be spirit-like. In this way his attributes become more and more great, and when his mind goes forth, whatever things come in his way, it lays hold of them (and deals with them). Thus, if there were not the Tâo, the bodily form would not have life, and its life, without the attributes (of the Tâo), would not be manifested. Is not he who preserves the body and gives the fullest development to the life, who establishes the attributes

of the Tâo and clearly displays It, possessed of kingly qualities? How majestic is he in his sudden issuings forth, and in his unexpected movements, when all things follow him!--This we call the man whose qualities fit him to rule.

'He sees where there is the deepest obscurity; he hears where there is no sound. In the midst of the deepest obscurity, he alone sees and can distinguish (various objects); in the midst of a soundless (abyss), he alone can hear a harmony (of notes). Therefore where one deep is succeeded by a greater, he can people all with things; where one mysterious range is followed by another that is more so, he can lay hold of the subtlest character of each. In this way in his intercourse with all things, while he is farthest from having anything, he can yet give to them what they seek; while he is always hurrying forth, he yet returns to his resting-place; now large, now small; now long, now short; now distant, now near 1.'

4. Hwang-Tî, enjoying himself on the north of the Red-water, ascended to the height of the Khwän-lun (mountain), and having looked towards the south, was returning home, when he lost his dark-coloured pearl 2. He employed Wisdom to search for it, but he could not find it. He employed (the clear-sighted) Lî Kû to search for it, but he

could not find it. He employed (the vehement debater) Khieh Khâu 1 to search for it, but he could not find it. He then employed Purposeless 1, who found it; on which Hwang-Tî said, 'How strange that it was Purposeless who was able to find it!'

5. The teacher of Yâo was Hsü Yû 2; of Hsü Yû, Nieh Khüeh 2; of Nieh Khüeh, Wang Î 2; of Wang Î, Pheî-î 2. Yâo asked Hsü Yû, saying, 'Is Nieh Khüeh fit to be the correlate of Heaven 3? (If you think he is), I will avail myself of the services of Wang Î to constrain him (to take my place).' Hsü Yû replied, 'Such a measure would be hazardous, and full of peril to the kingdom! The character of Nieh Khüeh is this;--he is acute, perspicacious, shrewd and knowing, ready in reply, sharp in retort, and hasty; his natural (endowments) surpass those of other men, but by his human qualities he seeks to obtain the Heavenly gift; he exercises his discrimination in suppressing his errors, but he does not know what is the source from which his errors arise. Make him the correlate of Heaven! He would employ the human qualities, so that no regard would be paid to the Heavenly gift. Moreover, he would assign different functions to the different parts of the one person 4.

Moreover, honour would be given to knowledge, and he would have his plans take effect with the speed of fire. Moreover, he would be the slave of everything he initiated. Moreover, he would be embarrassed by things. Moreover, he would be looking all round for the response of things (to his measures). Moreover, he would be responding to the opinion of the multitude as to what was right. Moreover, he would be changing as things changed, and would not begin to have any principle of constancy. How can such a man be fit to be the correlate of Heaven? Nevertheless, as there are the smaller branches of a family and the common ancestor of all its branches, he might be the father of a branch, but not the father of the fathers of all the branches 1. Such government (as he would conduct) would lead to disorder. It would be calamity in one in the position of a minister, and ruin if he were in the position of the sovereign.'

6. Yâo was looking about him at Hwâ 2, the border-warden of which said, 'Ha! the sage! Let me ask blessings on the sage! May he live long!'

[paragraph continues] Yâo said, 'Hush!' but the other went on, 'May the sage become rich!' Yâo (again) said, 'Hush!' but (the warden) continued, 'May the sage have many sons!' When Yâo repeated his 'Hush,' the warden said, 'Long life, riches, and many sons are what men wish for;--how is it that you alone do not wish for them?' Yâo replied, 'Many sons bring many fears; riches bring many troubles; and long life gives rise to many obloquies. These three things do not help to nourish virtue; and therefore I wish to decline them.' The warden rejoined, 'At first I considered you to be a sage; now I see in you only a Superior man. Heaven, in producing the myriads of the people, is sure to have appointed for them their several offices. If you had many sons, and gave them (all their) offices, what would you have to fear? If you had riches, and made other men share them with you, what trouble would you have? The sage finds his dwelling like the quail (without any choice of its own), and is fed like the fledgling; he is like the bird which passes on (through the air), and leaves no trace (of its flight). When good order prevails in the world, he shares in the general prosperity. When there is no such order, he cultivates his virtue, and seeks to be unoccupied. After a thousand years, tired of the world, he leaves it, and ascends among the immortals. He mounts on the white clouds, and arrives at the place of God. The three forms of evil do not reach him, his person is always free from misfortune;--what obloquy has he to incur?'

With this the border-warden left him. Yâo followed him, saying, 'I beg to ask--;' but the other said, 'Begone!'

7. When Yâo was ruling the world, Po-khäng Dze-kâo 1 was appointed by him prince of one of the states. From Yâo (afterwards) the throne passed to Shun, and from Shun (again) to Yû; and (then) Po-khäng Dze-kâo resigned his principality and began to cultivate the ground. Yü went to see him, and found him ploughing in the open country. Hurrying to him, and bowing low in acknowledgment of his superiority, Yü then stood up, and asked him, saying,' Formerly, when Yâo was ruling the world, you, Sir, were appointed prince of a state. He gave his sovereignty to Shun, and Shun gave his to me, when you, Sir, resigned your dignity, and are (now) ploughing (here);--I venture to ask the reason of your conduct.' Dze-kâo said, 'When Yâo ruled the world, the people stimulated one another (to what was right) without his offering them rewards, and stood in awe (of doing wrong) without his threatening them with punishments. Now you employ both rewards and punishments, and the people notwithstanding are not good. Their virtue will from this time decay; punishments will from this time prevail; the disorder of future ages will from this time begin. Why do you, my master, not go away, and not interrupt my work?' With this he resumed his ploughing with his head bent down, and did not (again) look round.

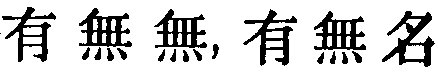

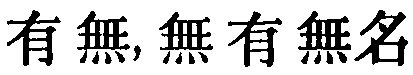

8. In the Grand Beginning (of all things) there was nothing in all the vacancy of space; there was nothing that could be named 2. It was in this state

that there arose the first existence 1;--the first existence, but still without bodily shape. From this things could then be produced, (receiving) what we call their proper character 2 . That which had no bodily shape was divided 3; and then without intermission there was what we call the process of conferring 4. (The two processes) continuing in operation, things were produced. As things were completed, there were produced the distinguishing lines of each, which we call the bodily shape. That shape was the body preserving in it the spirit 5, and each had its peculiar manifestation, which we call its Nature. When the Nature has been cultivated, it returns to its proper character; and when that has been fully reached, there is the same condition as at the Beginning. That sameness is pure vacancy, and the vacancy is great. It is like the closing of the beak and silencing the singing (of a bird). That closing and silencing is like the union of heaven and earth (at the beginning) 6. The union, effected, as it

is, might seem to indicate stupidity or darkness, but it is what we call the 'mysterious quality' (existing at the beginning); it is the same as the Grand Submission (to the Natural Course).

9. The Master 1 asked Lâo Tan, saying, 'Some men regulate the Tâo (as by a law), which they have only to follow;--(a thing, they say,) is admissible or it is inadmissible; it is so, or it is not so. (They are like) the sophists who say that they can distinguish what is hard and what is white as clearly as if the objects were houses suspended in the sky. Can such men be said to be sages 2?' The reply was, 'They are like the busy underlings of a court, who toil their bodies and distress their minds with their various artifices;--dogs, (employed) to their sorrow to catch the yak, or monkeys 3 that are brought from their forests (for their tricksiness). Khiû, I tell you this;-it is what you cannot hear, and what you cannot speak of:--Of those who have their heads and feet, and yet have neither minds nor ears, there are multitudes; while of those who have their bodies, and at the same time preserve that which has no bodily form or shape, there are really none. It is not in their movements or stoppages, their dying or living, their falling and rising again, that this is to be found. The regulation of the course lies in (their dealing with) the human element in them. When they have forgotten external things,

and have also forgotten the heavenly element in them, they may be named men who have forgotten themselves. The man who has forgotten himself is he of whom it is said that he has become identified with Heaven 1.'

10. At an interview with Kî Khêh 2, Kiang-lü Mien 2 said to him, 'Our ruler of Lû asked to receive my instructions. I declined, on the ground that I had not received any message 3 for him. Afterwards, however, I told him (my thoughts). I do not know whether (what I said) was right or not, and I beg to repeat it to you. I said to him, "You must strive to be courteous and to exercise self-restraint; you must distinguish the public-spirited and loyal, and repress the cringing and selfish;--who among the people will in that case dare not to be in harmony with you?"' Kî Khêh laughed quietly and said, 'Your words, my master, as a description of the right course for a Tî or King, were like the threatening movement of its arms by a mantis which would thereby stop the advance of a carriage;--inadequate to accomplish your object. And moreover, if he guided himself by your directions, it would be as if he were to increase the dangerous height of his towers

and add to the number of his valuables collected in them;--the multitudes (of the people) would leave their (old) ways, and bend their steps in the same direction.'

Kiang-lü Mien was awe-struck, and said in his fright, 'I am startled by your words, Master, nevertheless, I should like to hear you describe the influence (which a ruler should exert).' The other said, 'If a great sage ruled the kingdom, he would stimulate the minds of the people, and cause them to carry out his instructions fully, and change their manners; he would take their minds which had become evil and violent and extinguish them, carrying them all forward to act in accordance with the (good) will belonging to them as individuals, as if they did it of themselves from their nature, while they knew not what it was that made them do so. Would such an one be willing to look up to Yâo and Shun in their instruction of the people as his elder brothers? He would treat them as his juniors, belonging himself to the period of the original plastic ether 1. His wish would be that all should agree with the virtue (of that early period), and quietly rest in it.'

11. Dze-kung had been rambling in the south in Khû, and was returning to Zin. As he passed (a place) on the north of the Han, he saw an old man who was going to work on his vegetable garden. He had dug his channels, gone to the well, and was bringing from it in his arms a jar of water to pour into them. Toiling away, he expended a great deal

of strength, but the result which he accomplished was very small. Dze-kung said to him, 'There is a contrivance here, by means of which a hundred plots of ground may be irrigated in one day. With the expenditure of a very little strength, the result accomplished is great. Would you, Master, not like (to try it)?' The gardener looked up at him, and said, 'How does it work?' Dze-kung said, 'It is a lever made of wood, heavy behind, and light in front. It raises the water as quickly as you could do with your hand, or as it bubbles over from a boiler. Its name is a shadoof.' The gardener put on an angry look, laughed, and said, 'I have heard from my teacher that, where there are ingenious contrivances, there are sure to be subtle doings; and that, where there are subtle doings, there is sure to be a scheming mind. But, when there is a scheming mind in the breast, its pure simplicity is impaired. When this pure simplicity is impaired, the spirit becomes unsettled, and the unsettled spirit is not the proper residence of the Tâo. It is not that I do not know (the contrivance which you mention), but I should be ashamed to use it.'

(At these words) Dze-kung looked blank and ashamed; he hung down his head, and made no reply. After an interval, the gardener said to him, 'Who are you, Sir? A disciple of Khung Khiû,' was the reply. The other continued, 'Are you not the scholar whose great learning makes you comparable to a sage, who make it your boast that you surpass all others, who sing melancholy ditties all by yourself, thus purchasing a famous reputation throughout the kingdom? If you would (only) forget the energy of your spirit, and neglect the care of

your body, you might approximate (to the Tâo). But while you cannot regulate yourself, what leisure have you to be regulating the world? Go on your way, Sir, and do not interrupt my work.'

Sze-kung shrunk back abashed, and turned pale. He was perturbed, and lost his self-possession, nor did he recover it, till he had walked a distance of thirty lî. His disciples then said, 'Who was that man? Why, Master, when you saw him, did you change your bearing, and become pale, so that you have been all day without returning to yourself?' He replied to them,' Formerly I thought that there was but one man 1 in the world, and did not know that there was this man. I have heard the Master say that to seek for the means of conducting his undertakings so that his success in carrying them out may be complete, and how by the employment of a little strength great results may be obtained, is the way of the sage. Now (I perceive that) it is not so at all. They who hold fast and cleave to the Tâo are complete in the qualities belonging to it. complete in those qualities, they are complete in their bodies. Complete in their bodies, they are complete in their spirits. To be complete in spirit is the way of the sage. (Such men) live in the world in closest union with the people, going along with them, but they do not know where they are going. Vast and complete is their simplicity! Success, gain, and ingenious contrivances, and artful cleverness, indicate (in their opinion) a forgetfulness of the (proper) mind of man. These men will not go where their mind does not carry them, and will do

nothing of which their mind does not approve. Though all the world should praise them, they would (only) get what they think should be loftily disregarded; and though all the world should blame them, they would but lose (what they think) fortuitous and not to be received;-the world's blame and praise can do them neither benefit nor injury. Such men may be described as possessing all the attributes (of the Tâo), while I can only be called one of those who are like the waves carried about by the wind.' When he returned to Lû, (Dze-kung) reported the interview and conversation to Confucius, who said, 'The man makes a pretence of cultivating the arts of the Embryonic Age 1. He knows the first thing, but not the sequel to it. He regulates what is internal in himself, but not what is external to himself. If he had intelligence enough to be entirely unsophisticated, and by doing nothing to seek to return to the normal simplicity, embodying (the instincts of) his nature, and keeping his spirit (as it were) in his arms, so enjoying himself in the common ways, you might then indeed be afraid of him! But what should you and I find in the arts of the embryonic time, worth our knowing?'

12. Kun Mang 2, on his way to the ocean, met with Yüan Fung 2 on the shore of the eastern sea, and

was asked by him where he was going. 'I am going,' he replied, 'to the ocean;' and the other again asked, 'What for?' Kun Mâng said, 'Such is the nature of the ocean that the waters which flow into it can never fill it, nor those which flow from it exhaust it. I will enjoy myself, rambling by it.' Yüan Fung replied, 'Have you no thoughts about mankind 1? I should like to hear from you about sagely government.' Kun Mâng said,' Under the government of sages, all offices are distributed according to the fitness of their nature; all appointments are made according to the ability of the men; whatever is done is after a complete survey of all circumstances; actions and words proceed from the inner impulse, and the whole world is transformed. Wherever their hands are pointed and their looks directed, from all quarters the people are all sure to come (to do what they desire):--this is what is called government by sages.'

'I should like to hear about (the government of) the kindly, virtuous men 2,' (continued Yüan Fung). The reply was, 'Under the government of the virtuous, when quietly occupying (their place), they have no thought, and, when they act, they have no anxiety; they do not keep stored (in their minds) what is right and what is wrong, what is good and

what is bad. They share their benefits among all within the four seas, and this produces what is called (the state of) satisfaction; they dispense their gifts to all, and this produces what is called (the state of) rest. (The people) grieve (on their death) like babies who have lost their mothers, and are perplexed like travellers who have lost their way. They have a superabundance of wealth and all necessaries, and they know not whence it comes; they have a sufficiency of food and drink, and they know not from whom they get it:--such are the appearances (under the government) of the kindly and virtuous.'

'I should like to hear about (the government of) the spirit-like men,' (continued Yüan Fung once more).

The reply was, 'Men of the highest spirit-like qualities mount up on the light, and (the limitations of) the body vanish. This we call being bright and ethereal. They carry out to the utmost the powers with which they are endowed, and have not a single attribute unexhausted. Their joy is that of heaven and earth, and all embarrassments of affairs melt away and disappear; all things return to their proper nature:--and this is what is called (the state of) chaotic obscurity 1.'

13. Män Wû-kwei 2 and Khih-kang Man-khî 2 had been looking at the army of king Wû, when the latter said, 'It is because he was not born in the time of the Lord of Yü 3, that therefore he is involved

in this trouble (of war).' Män Wû-kwei replied, 'Was it when the kingdom was in good order, that the Lord of Yü governed it? or was it after it had become disordered that he governed it?' The other said, 'That the kingdom be in a condition of good order, is what (all) desire, and (in that case) what necessity would there be to say anything about the Lord of Yü? He had medicine for sores; false hair for the bald; and healing for those who were ill:--he was like the filial son carrying in the medicine to cure his kind father, with every sign of distress in his countenance. A sage would be ashamed (of such a thing) 1.

'In the age of perfect virtue they attached no value to wisdom, nor employed men of ability. Superiors were (but) as the higher branches of a tree; and the people were like the deer of the wild. They were upright and correct, without knowing that to be so was Righteousness; they loved one another, without knowing that to do so was Benevolence; they were honest and leal-hearted, without knowing that it was Loyalty; they fulfilled their engagements, without knowing that to do so was Good Faith; in their simple movements they employed the services of one another, without thinking that they were conferring or receiving any gift. Therefore their actions left no trace, and there was no record of their affairs.'

14. The filial son who does not flatter his father,

and the loyal minister who does not fawn on his ruler, are the highest examples of a minister and a son. When a son assents to all that his father says, and approves of all that his father does, common opinion pronounces him an unworthy son; when a minister assents to all that his ruler says, and approves of all that his ruler does, common opinion pronounces him an unworthy minister. Nor does any one reflect that this view is necessarily correct 1. But when common opinion (itself) affirms anything and men therefore assent to it, or counts anything good and men also approve of it, then it is not said that they are mere consenters and flatterers;--is common opinion then more authoritative than a father, or more to be honoured than a ruler? Tell a man that he is merely following (the opinions) of another, or that he is a flatterer of others, and at once he flushes with anger. And yet all his life he is merely following others, and flattering them. His illustrations are made to agree with theirs; his phrases are glossed:--to win the approbation of the multitudes. From first to last, from beginning to end, he finds no fault with their views. He will let his robes hang down 2, display the colours on them, and arrange his movements and bearing, so as to win the favour of his age, and yet not call himself a flatterer. He is but a follower of those others, approving and disapproving

as they do, and yet he will not say that he is one of them. This is the height of stupidity.

He who knows his stupidity is not very stupid; he who knows that he is under a delusion is not greatly deluded. He who is greatly deluded will never shake the delusion off; he who is very stupid will all his life not become intelligent. If three men be walking together, and (only) one of them be under a delusion (as to their way), they may yet reach their goal, the deluded being the fewer; but if two of them be under the delusion, they will not do so, the deluded being the majority. At the present time, when the whole world is under a delusion, though I pray men to go in the right direction, I cannot make them do so;--is it not a sad case?

Grand music does not penetrate the ears of villagers; but if they hear 'The Breaking of the Willow,' or 'The Bright Flowers 1,' they will roar with laughter. So it is that lofty words do not remain in the minds of the multitude, and that perfect words are not heard, because the vulgar words predominate. By two earthenware instruments the (music of) a bell will be confused, and the pleasure that it would afford cannot be obtained. At the present time the whole world is under a delusion, and though I wish to go in a certain direction, how can I succeed in doing so? Knowing that I cannot do so, if I were to try to force my way, that would be another delusion. Therefore my best course is to let my purpose go, and no more pursue it. If I do not pursue it, whom shall 1 have to share in my sorrow 2?

If an ugly man 1 have a son born to him at midnight, he hastens with a light to look at it. Very eagerly he does so, only afraid that it may be like himself.

15 2. From a tree a hundred years old a portion shall be cut and fashioned into a sacrificial vase, with the bull figured on it, which is ornamented further with green and yellow, while the rest (of that portion) is cut away and thrown into a ditch. If now we compare the sacrificial vase with what was thrown into the ditch, there will be a difference between them as respects their beauty and ugliness; but they both agree in having lost the (proper) nature of the wood. So in respect of their practice of righteousness there is a difference between (the robber) Kih on the one hand, and Zäng (Shän) or Shih (Zhiû) on the other; but they all agree in having lost (the proper qualities of) their nature.

Now there are five things which produce (in men) the loss of their (proper) nature. The first is (their fondness for) the five colours which disorder the eye, and take from it its (proper) clearness of vision; the second is (their fondness for) the five notes (of music), which disorder the ear and take from it its

(proper) power of hearing; the third is (their fondness for) the five odours which penetrate the nostrils, and produce a feeling of distress all over the forehead; the fourth is (their fondness for) the five flavours, which deaden the mouth, and pervert its sense of taste; the fifth is their preferences and dislikes, which unsettle the mind, and cause the nature to go flying about. These five things are all injurious to the life; and now Yang and Mo begin to stretch forward from their different standpoints, each thinking that he has hit on (the proper course for men).

But the courses they have hit on are not what I call the proper course. What they have hit on (only) leads to distress;--can they have hit on what is the right thing? If they have, we may say that the dove in a cage has found the right thing for it. Moreover, those preferences and dislikes, that (fondness for) music and colours, serve but to pile up fuel (in their breasts); while their caps of leather, the bonnet with kingfishers' plumes, the memorandum tablets which they carry, and their long girdles, serve but as restraints on their persons. Thus inwardly stuffed full as a hole for fuel, and outwardly fast bound with cords, when they look quietly round from out of their bondage, and think they have got all they could desire, they are no better than criminals whose arms are tied together, and their fingers subjected to the screw, or than tigers and leopards in sacks or cages, and yet thinking that they have got (all they could wish).

307:2 Implying that that ruler, 'the Son of Heaven,' is only one.

307:3 'Heaven' is here defined as meaning 'Non-action, what is of itself (

);' the teh (

);' the teh (

) is the virtue, or qualities of the Tâo;--see the first paragraph of the next Book.

) is the virtue, or qualities of the Tâo;--see the first paragraph of the next Book.

307:4 This sentence gives the thesis, or subject-matter of the whole Book, which the author never loses sight of.

307:5 Perhaps we should translate here, 'They looked at their words,' referring to 'the ancient rulers.' So Gabelentz construes:--'Dem Tâo gemäss betrachteten sie die reden.' The meaning that I have given is substantially the same. The term 'words' occasions a difficulty. I understand it here, with most of the critics, as

, the words of appellation.'

, the words of appellation.'

308:1 Meaning, probably, his appellation as Thien Dze, 'the Son of Heaven.'

308:2 That is, 'they responded to the Tâo,' without any constraint but the example of their rulers.

308:3 Here there would seem to be a quotation which I have not been able to trace to its source.

308:4 This 'Record' is attributed to Lâo-dze; but we know nothing of it. In illustration of the sentiment in the sentence, the critics refer to par. 34 in the fourth Appendix to the Yî King; but it is not to the point.

309:1 Who is 'the Master' here? Confucius? or Lâo-dze? I think the latter, though sometimes even our author thus denominates Confucius;--see par. 9.

309:2 ? the Tâo.

310:1 Balfour:--'The difference between life and death exists no more;' Gabelentz:--'Sterben und Leben haben gleiche Erscheinung.'

311:1 I can hardly follow the reasoning of Kwang-dze here. The whole of the paragraph is obscure. I have translated the two concluding characters

as if they were

as if they were

, after the example of Lin Hsî-yî, whose edition of Kwang-dze was first published in 1261.

, after the example of Lin Hsî-yî, whose edition of Kwang-dze was first published in 1261.

311:2 Meaning the Tâo. This is not to be got or learned by wisdom, or perspicacity, or man's reasoning. It is instinctive to man, as the Heavenly gift or Truth (

).

).

312:1 The meaning of the characters shows what is the idea emblemed by this name; and so with Hsiang Wang,--'a Semblance,' and 'Nonentity;' = 'Mindless,' 'Purposeless.'

312:2 All these names have occurred, excepting that of Pheî-î, who heads Hwang-fû Mî's list of eminent Tâoists. We shall meet with him again. He is to be distinguished from Phû-î.

312:3 'Match Heaven;' that is, be sovereign below, as Heaven above ruled all.

312:4 We are referred for the meaning of this characteristic to

, in Bk. V, Par. 1.

, in Bk. V, Par. 1.

313:1 That is, Nieh might be a minister, but could not be the sovereign. The phraseology is based on the rules for the rise of sub-surnames in the same clan, and the consequent division of clans under different ancestors;--see the Lî Kî, Bk. XIII, i, 10-14, and XIV, 8.

313:2 'Hwâ' is evidently intended for the name of a place, but where it was can hardly be determined. The genuineness of the whole paragraph is called in question; and I pass it by, merely calling attention to what the border-warden is made to say about the close of the life of the sage (Tâoist), who after living a thousand years, ascends among the Immortals (

=

=

), and arrives at the place of God, and is free from the three evils of disease, old age, and death; or as some say, after the Buddhists, water, fire, and wind!

), and arrives at the place of God, and is free from the three evils of disease, old age, and death; or as some say, after the Buddhists, water, fire, and wind!

315:1 Some legends say that this Po-khäng Dze-kâo was a pre-incarnation of Mo-dze; but this paragraph is like the last, and cannot be received as genuine.

315:2 This sentence is differently understood, according as it is p. 316 punctuated;--

, or

, or

. Each punctuation has its advocates. For myself, I can only adopt the former; the other is contrary to my idea of Chinese composition. If the author had wished to be understood so, he would have written differently, as, for instance,

. Each punctuation has its advocates. For myself, I can only adopt the former; the other is contrary to my idea of Chinese composition. If the author had wished to be understood so, he would have written differently, as, for instance,

.

.

316:1 Probably, the primary ether, what is called the Thâi Kih.

316:2 This sentence is anticipatory.

316:3 Into what we call the yin and the yang;--the same ether, now at rest, now in motion.

316:4 The conferring of something more than what was material. By whom or what? By Heaven; the Tâoist understanding by that term the Tâo.

316:5 So then, man consists of the material body and the immaterial spirit.

316:6 The potential heaven and earth, not yet fashioned from the primal ether.

317:1 This 'Master' is without doubt Confucius.

317:2 The meaning and point of Confucius's question are not clear. Did he mean to object to Lao-dze that all his disquisitions about the Tâo as the one thing to be studied and followed were unnecessary?

317:3 Compare in Bk. VII, par. 4.

318:1 Their action is like that of Heaven, silent but most effective, without motive from within or without, simply from the impulse of the Tâo.

318:2 These two men are only known by the mention of them here. They must have been officers of Lû, Kî Khêh a member of the great Kî or Kî-sun family of that state. He would appear also to have been the teacher of the other; if, indeed, they were real personages, and not merely the production of Kwang-dze's imagination.

318:3 That is any lessons or instructions from you, my master, which I should communicate to him.

319:1 The Chinese phrase here is explained by Dr. Williams:--'A vivifying influence, a vapour or aura producing things.'

321:1 Confucius.

322:1 The 'arts of the Embryonic Age' suggests the idea of the earliest men in their struggles for support; not the Tâo of Heaven in its formation of the universe. But the whole of the paragraph, not in itself uninteresting, is believed to be a spurious introduction, and not the production of Kwang-dze.

322:2 These are not names of men, but like Yün Kiang and Hung Mung in the fifth paragraph of the last Book. By Kim Ming, it is said, we are to understand 'the great primal ether,' and by Yüan p. 323 Fung, 'the east wind.' Why these should discourse together as they are here made to do, only Kwang-dze himself could tell.

323:1 Literally, 'men with their cross eyes;' an appellation for mankind, men having their eyes set across their face more on the same plane than other animals;--'an extraordinary application of the characters,' says Lin Hsî-kung.

323:2 The text is simply 'virtuous men;' but the reply justifies us in giving the meaning as 'kindly' as well.

has often this signification.

has often this signification.

324:1 'When no human element had come in to mar the development of the Tâo.

324:2 If these be the names of real personages, they must have been of the time of king Wû, about B. C. 1122.

324:3 Generally understood to mean 'He is not equal to the Lord of p. 325 Yü,' or Shun. The meaning which I have given is that propounded by Hû Wan-ying, and seems to agree better with the general purport of the paragraph.

325:1 Ashamed that he had not been able to keep his father from getting sick, and requiring to be thus attended to.

326:1 We can hardly tell whether this paragraph should be understood as a continuation of Khih-kang's remarks, or as from Kwang-dze himself. The meaning here is that every one feels that this opinion is right, without pausing to reason about it.

326:2 See the Yî King, Appendix III, ii, 15, where this letting his robes hang down is attributed to Shun. Ought we to infer from this that in this paragraph we have Khih-kang still speaking about and against the common opinion of Shun's superiority to king Wû?

327:1 The names of two songs, favourites with the common people.

327:2 I shall only feel the more that I am alone without any to sympathise with me, and be the more sad.

328:1

should perhaps be translated 'a leper.' The illustration is edited by Kiâo Hung and others as a paragraph by itself; They cannot tell whether it be intended to end the paragraph that precedes or to introduce the one that follows.

should perhaps be translated 'a leper.' The illustration is edited by Kiâo Hung and others as a paragraph by itself; They cannot tell whether it be intended to end the paragraph that precedes or to introduce the one that follows.

328:2 This paragraph must be our author's own. Khih-kang, of the time of king Wû, could not be criticising the schemes of life propounded by Mo and Yang, whose views were so much later in time. It breathes the animosity of Lâo and Kwang against all schemes of learning and culture, as contrary to the simplicity of life according to the Tâo.