Sacred Texts Legendary Creatures Index Previous Next

Buy this Book at Amazon.com

Evolution of the Dragon, by G. Elliot Smith, [1919], at sacred-texts.com

The most important and fundamental legend in the whole history of mythology is the story of the "Destruction of Mankind". "It was discovered, translated, and commented upon by Naville ("La Destruction des hommes par les Dieux," in the Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archæology, vol. iv., pp. 1-19, reproducing Hay's copies made at the beginning of [the nineteenth] century; and

[paragraph continues] "L’inscription de la Destruction des hommes dans le tombeau de Ramsès III," in the Transactions, vol. viii., pp. 412-20); afterwards published anew by Herr von Bergmann (Hieroglyphische Inscriften, pls. lxxv.–lxxxii., and pp. 55, 56); completely translated by Brugsch (Die neue Weltordnung nach Vernichtung des sündigen Menschengeschlechts nach einer Altägyptischen Ueber lieferung, 1881); and partly translated by Lauth (Aus Ægyptens Vorzeit, pp. 70-81) and by Lefèbure ("Une chapitre de la chronique solaire," in the Zeitschrift für Ægyptische Sprache, 1883, pp. 32, 33)" 1

Important commentaries upon this story have been published also by Brugsch and Gauthier. 2

As the really important features of the story consist of the incoherent and contradictory details, and it would take up too much space to reproduce the whole legend here, I must refer the reader to Maspero's account of it (op. cit.), or to the versions given by Erman in his "Life in Ancient Egypt" (p. 267, from which I quote) or Budge in "The Gods of the Egyptians," vol. i., p. 388.

Although the story as we know it was not written down until the time of Seti I (circa 1300 B.C.), it is very old and had been circulating as a popular legend for more than twenty centuries before that time. The narrative itself tells its own story because it is composed of many contradictory interpretations of the same incidents flung together in a highly confused and incoherent form.

The other legends to which I shall have constantly to refer are "The Saga of the Winged Disk," "The Feud between Horus and Set," "The Stealing of Re's Name by Isis," and a series of later variants and confusions of these stories. 3

The Egyptian legends cannot be fully appreciated unless they are studied in conjunction with those of Babylonia and Assyria, 1 the mythology of Greece, 2 Persia, 3 India, 4 China, 5 Indonesia, 6 and America. 7

For it will be found that essentially the same stream of legends was flowing in all these countries, and that the scribes and painters have caught and preserved certain definite phases of this verbal currency. The legends which have thus been preserved are not to be regarded as having been directly derived the one from the other but as collateral phases of a variety of waves of story spreading out from one centre. Thus the comparison of the whole range of homologous legends is peculiarly instructive and useful; because the gaps in the Egyptian series, for example, can be filled in by necessary phases which are missing in Egypt itself, but are preserved in Babylonia or Greece, Persia or India, China or Britain, or even Oceania and America.

The incidents in the Destruction of Mankind may be briefly summarized:—

As Re grows old "the men who were begotten of his eye" 8 show signs of rebellion. Re calls a council of the gods and they advise him

to "shoot forth his Eye 1 that it may slay the evil conspirators. … Let the goddess Hathor descend [from heaven] and slay the men on the mountains [to which they had fled in fear]." As the goddess complied she remarked: "it will be good for me when I subject mankind," and Re replied, "I shall subject them and slay them". Hence the goddess received the additional name of Sekhmet from the word "to subject". The destructive Sekhmet 2 avatar of Hathor is represented as a fierce lion-headed goddess of war wading in blood. For the goddess set to work slaughtering mankind and the land was flooded with blood. 3 Re became alarmed and determined to save at least some remnant of mankind. For this purpose he sent messengers to Elephantine to obtain a substance called d’d’ in the Egyptian text, which he gave to the god Sektet of Heliopolis to grind up in a mortar. When the slaves had crushed barley to make beer the powdered d’d’ was mixed with it so as to make it red like human blood. Enough of this blood-coloured beer was made to fill 7000 jars. At nighttime this was poured out upon the fields, so that when the goddess came to resume her task of destruction in the morning she found the fields inundated and her face was mirrored in the fluid. She drank of the fluid and became intoxicated so that she no longer recognized mankind. 4

Thus Re saved a remnant of mankind from the bloodthirsty, terrible Hathor. But the god was weary of life on earth and withdrew to heaven upon the back of the Divine Cow.

There can be no doubt as to the meaning of this legend, highly confused as it is. The king who was responsible for introducing irrigation

came to be himself identified with the life-giving power of water. He was the river: his own vitality was the source of all fertility and prosperity. Hence when he showed signs that his vital powers were failing it became a logical necessity that he should be killed to safeguard the welfare of his country and people. 1

The time came when a king, rich in power and the enjoyment of life, refused to comply with this custom. When he realized that his virility was failing he consulted the Great Mother, as the source and giver of life, to obtain an elixir which would rejuvenate him and obviate the necessity of being killed. The only medicine in the pharmacopoeia of those times that was believed to be useful in minimizing danger to life was human blood. Wounds that gave rise to severe hæmorrhage were known to produce unconsciousness and death. If the escape of

the blood of life could produce these results it was not altogether illogical to assume that the exhibition of human blood could also add to the vitality of living men and so "turn back the years from their old age," as the Pyramid Texts express it.

Thus the Great Mother, the giver of life to all mankind, was faced with the dilemma that, to provide the king with the elixir to restore his youth, she had to slay mankind, to take the life she herself had given to her own children. Thus she acquired an evil reputation which was to stick to her throughout her career. She was not only the beneficent creator of all things and the bestower of all blessings: but she was also a demon of destruction who did not hesitate to slaughter even her own children.

In course of time the practice of human sacrifice was abandoned and substitutes were adopted in place of the blood of mankind. Either the blood of cattle, 1 who by means of appropriate ceremonies could be transformed into human beings (for the Great Mother herself was the Divine Cow and her offspring cattle), was employed in its stead; or red ochre was used to colour a liquid which was used ritually to replace the blood of sacrifice. When this phase of culture was reached the goddess provided for the king an elixir of life consisting of beer stained red by means of red ochre, so as to simulate human blood.

But such a mixture was doubly potent, for the barley from which the beer was made and the drink itself was supposed to be imbued with the life-giving powers of Osiris, and the blood-colour reinforced its therapeutic usefulness. The legend now begins to become involved and confused. For the goddess is making the rejuvenator for the king, who in the meantime has died and become deified as Osiris; and the beer, which is the vehicle of the life-giving powers of Osiris, is now being used to rejuvenate his son and successor, the living king Horus, who in the version that has come down to us is replaced by the sun-god Re.

It is Re who is king and is growing old: he asks Hathor, the Great Mother, to provide him with the elixir of life. But comparison with some of the legends of other countries suggests that Re has usurped the place previously occupied by Horus and originally by Osiris, who as the real personification of the life-giving power of water is obviously the appropriate person to be slain when his virility begins to fail. Dr. C. G. Seligman's account of the Dinka rain-maker Lerpiu, which I have already quoted (p. 113) from Sir James Frazer's "Dying God," suggests that the slain king or god was originally Osiris.

The introduction of Re into the story marks the beginning of the belief in the sky-world or heaven. Hathor was originally nothing more than an amulet to enhance fertility and vitality. Then she was personified as a woman and identified with a cow. But when the view developed that the moon controlled the powers of life-giving in women and exercised a direct influence upon their life-blood, the Great Mother was identified with the moon. But how was such a conception to be brought into harmony with the view that she was also a cow? The human mind displays an irresistible tendency to unify its experience and to bridge the gaps that necessarily exist in its broken series of scraps of knowledge and ideas. No break is too great to be bridged by this instinctive impulse to rationalize the products of diverse experience. Hence, early man, having identified the Great Mother both with a cow and the moon, had no compunction in making "the cow jump over the moon" to become the sky. The moon then became the "Eye" of the sky and the sun necessarily became its other "Eye". But, as the sun was clearly the more important "Eye," seeing that it determined the day and gave warmth and light for man's daily work, it was the more important deity. Therefore Re, at first the Brother-Eye of Hathor, and afterwards her husband, became the supreme sky-deity, and Hathor merely one of his Eyes.

When this stage of theological evolution was reached, the story of the "Destruction of Mankind" was re-edited, and Hathor was called the "Eye of Re". In the earlier versions she was called into consultation solely as the giver of life and, to obtain the life-blood, she cut men's throats with a knife.

But as the Eye of Re she was identified with the fire-spitting uræus-serpent which the king or god wore on his forehead. She was both the moon and the fiery bolt which shot down from the sky to slay

the enemies of Re. For the men who were originally slaughtered to provide the blood for an elixir now became the enemies of Re. The reason for this was that, human sacrifice having been abandoned and substitutes provided to replace the human blood, the story-teller was at a loss to know why the goddess killed mankind. A reason had to be found—and the rationalization adopted was that men had rebelled against the gods and had to be killed. This interpretation was probably the result of a confusion with the old legend of the fight between Horus and Set, the rulers of the two kingdoms of Egypt. The possibility also suggests itself that a pun made by some priestly jester may have been the real factor that led to this mingling of two originally separate stories. In the "Destruction of Mankind" the story runs, according to Budge, 1 that Re, referring to his enemies, said: mā-ten set uār er set, "Behold ye them (set) fleeing into the mountain (set)". The enemies were thus identified with the mountain or stone and with Set, the enemy of the gods. 2

In Egyptian hieroglyphics the symbol for stone is used as the determinative for Set. When the "Eye of Re" destroyed mankind and the rebels were thus identified with the followers of Set, they were regarded as creatures of "stone". In other words the Medusa-eye petrified the enemies. From this feeble pun on the part of some ancient Egyptian scribe has arisen the world-wide stories of the influence of the "Evil Eye" and the petrification of the enemies of the gods. 3 As the name for Isis in Egyptian is "Set," it is possible that the confusion of the Power of Evil with the Great Mother may also have been facilitated by an extension of the same pun.

It is important to recognize that the legend of Hathor descending from the moon or the sky in the form of destroying fire had nothing whatever to do, in the first instance, with the phenomena of lightning

and meteorites. It was the result of verbal quibbling after the destructive goddess came to be identified with the moon, the sky and the "Eye of Re". But once the evolution of the story on these lines prepared the way, it was inevitable that in later times the powers of destruction exerted by the fire from the sky should have been identified with the lightning and meteorites.

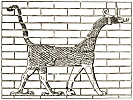

When the destructive force of the heavens was attributed to the "Eye of Re" and the god's enemies were identified with the followers of Set, it was natural that the traditional enemy of Set who was also the more potent other "Eye of Re" should assume his mother's rôle of punishing rebellious mankind. That Horus did in fact take the place at first occupied by Hathor in the story is revealed by the series of trivial episodes from the "Destruction of Mankind" that reappear in the "Saga of the Winged Disk". The king of Lower Egypt (Horus) was identified with a falcon, as Hathor was with the vulture (Mut): like her, he entered the sun-god's boat 1 and sailed up the river with him: he then mounted up to heaven as a winged disk, i.e. the sun of Re equipped with his own falcon's wings. The destructive force displayed by Hathor as the Eye of Re was symbolized by her identification with Tefnut, the fire-spitting uræus-snake. When Horus assumed the form of the winged disk he added to his insignia two fire-spitting serpents to destroy Re's enemies. The winged disk was at once the instrument of destruction and the god himself. It swooped (or flew) down from heaven like a bolt of destroying fire and killed the enemies of Re. By a confusion with Horus's other fight against the

followers of Set, the enemies of Re become identified with Set's army and they are transformed into crocodiles, hippopotami and all the other kinds of creatures whose shapes the enemies of Osiris assume.

In the course of the development of these legends a multitude oft other factors played a part and gave rise to transformations of the meaning of the incidents.

The goddess originally slaughtered mankind, or perhaps it would be truer to say, made a human sacrifice, to obtain blood to rejuvenate the king. But, as we have seen already, when the sacrifice was no longer a necessary part of the programme, the incident of the slaughter was not dropped out of the story, but a new explanation of it was framed. Instead of simply making a human sacrifice, mankind as a whole was destroyed for rebelling against the gods, the act of rebellion being murmuring about the king's old age and loss of virility. The elixir soon became something more than a rejuvenator: it was transformed into the food of the gods, the ambrosia that gave them their immortality, and distinguished them from mere mortals. Now when the development of the story led to the replacement of the single victim by the whole of mankind, the blood produced by the wholesale slaughter was so abundant that the fields were flooded by the life-giving elixir. By the sacrifice of men the soil was renewed and refertilized. When the blood-coloured beer was substituted for the actual blood the conception was brought into still closer harmony with Egyptian ideas, because the beer was animated with the life-giving powers of Osiris. But Osiris was the Nile. The blood-coloured fertilizing fluid was then identified with the annual inundation of the red-coloured waters of the Nile. Now the Nile waters were supposed to come from the First Cataract at Elephantine. Hence by a familiar psychological process the previous phase of the legend was recast, and by confusion the red ochre (which was used to colour the beer red) was said to have come from Elephantine. 1

Thus we have arrived at the stage where, by a distortion of a series of phases, the new incident emerges that by means of a human sacrifice the Nile flood can be produced. By a further confusion the goddess, who originally did the slaughter, becomes the victim. Hence the story assumed the form that by means of the sacrifice of a beautiful and attractive maiden the annual inundation can be produced. As the most potent symbol of life-giving it is essential that the victim should be sexually attractive, i.e. that she should be a virgin and the most beautiful and desirable in the land. When the practice of human sacrifice was abandoned a figure or an animal was substituted for the maiden in ritual practice, and in legends the hero rescued the maiden, as Andromeda was saved from the dragon. 1 The dragon is the personification of the monsters that dwell in the waters as well as the destructive forces of the flood itself. But the monsters were no other than the followers of Set; they were the victims of the slaughter who became identified with the god's other traditional enemies, the followers of Set. Thus the monster from whom Andromeda is rescued is merely another representative of herself!

But the destructive forces of the flood now enter into the programme. In the phases we have so far discussed it was the slaughter of mankind which caused the inundation: but in the next phase it is the flood itself which causes the destruction, as in the later Egyptian and the borrowed Sumerian, Babylonian, Hebrew—and in fact the world-wide—versions. Re's boat becomes the ark; the winged disk which was despatched by Re from the boat becomes the dove and the other birds sent out to spy the land, as the winged Horus spied the enemies of Re.

Thus the new weapon of the gods—we have already noted Hathor's knife and Horus's winged disk, which is the fire from heaven, the lightning and the thunderbolt—is the flood. Like the others it can be either a beneficent giver of life or a force of destruction.

But the flood also becomes a weapon of another kind. One of the earlier incidents of the story represents Hathor in opposition to Re. The goddess becomes so maddened with the zest of killing that the god becomes alarmed and asks her to desist and spare some representatives of the race. But she is deaf to entreaties. Hence the god is,

said to have sent to Elephantine for the red ochre to make a sedative draught to overcome her destructive zeal. We have already seen that this incident had an entirely different meaning—it was merely intended to explain the obtaining of the colouring matter wherewith to redden the sacred beer so as to make it resemble blood as an elixir for the god. It was brought from Elephantine, because the red waters of inundation of the Nile were supposed by the Egyptians to come from Elephantine.

But according to the story inscribed in Seti Ist's tomb, the red ochre was an essential ingredient of the sedative mixture (prepared under the direction of Re by the Sekti 1 of Heliopolis) to calm Hathor's murderous spirit.

It has been claimed that the story simply means that the goddess became intoxicated with beer and that she became genially inoffensive solely as the effect of such inebriation. But the incident in the Egyptian story closely resembles the legends of other countries in which some herb is used specifically as a sedative. In most books on Egyptian mythology the word (d’d’) for the substance put into the drink to colour it is translated "mandragora," from its resemblance to the Hebrew word dudaim in the Old Testament, which is often translated "mandrakes" or "love-apples". But Gauthier has clearly demonstrated that the Egyptian word does not refer to a vegetable but to a mineral substance, which he translates "red clay" 2. Mr. F. Ll. Griffith tells me, however, that it is "red ochre". In any case, mandrake is not found at Elephantine (which, however, for the reasons I have already given, is a point of no importance so far as the identification of the substance is concerned), nor in fact anywhere in Egypt.

But if some foreign story of the action of a sedative drug had become blended with and incorporated in the highly complex and composite Egyptian legend the narrative would be more intelligible. The mandrake is such a sedative as might have been employed to calm the murderous frenzy of a maniacal woman. In fact it is closely allied to hyoscyamus, whose active principle, hyoscin, is used in modern medicine precisely for such purposes. I venture to suggest that a folk-tale describing the effect of opium or some other "drowsy syrup" has been absorbed into the legend of the Destruction of Mankind, and has provided the starting point of all those incidents in the dragon-story in which poison or some

sleep-producing drug plays a part. For when Hathor defies Re and continues the destruction, she is playing the part of her Babylonian representative Tiamat, and is a dragon who has to be vanquished by the drink which the god provides.

The red earth which was pounded in the mortar to make the elixir of life and the fertilizer of the soil also came to be regarded as the material out of which the new race of men was made to replace those who were destroyed.

The god fashioned mankind of this earth and, instead of the red ochre being merely the material to give the blood-colour to the draught of immortality, the story became confused: actual blood was presented to the clay images to give them life and consciousness.

In a later elaboration the remains of the former race of mankind were ground up to provide the material out of which their successors were created. This version is a favourite story in Northern Europe, and has obviously been influenced by an intermediate variant which finds expression in the Indian legend of the Churning of the Ocean of Milk. Instead of the material for the elixir of the gods being pounded by the Sekti of Heliopolis and incidentally becoming a sedative for Hathor, it is the milk of the Divine Cow herself which is churned to provide the amrita.

110:1 G. Maspero, "The Dawn of Civilization," p. 164.

110:2 H. Brugsch, "Die Alraune als altägyptische Zauberpflanze," Zeit. f. Ægypt. Sprache, Bd. 29, 1891, pp. 31-3; and Henri Gauthier, "Le nom hiéroglyphique de l’argile rouge d’Éléphantine," Revue Égyptologique, t. xie, Nos. i.–ii., 1904, p. 1.

110:3 These legends will be found in the works by Maspero, Erman and Budge, to which I have already referred. A very useful digest will be found in Donald A. Mackenzie's "Egyptian Myth and Legend". Mr. Mackenzie does not claim to have any first-hand knowledge of the subject, but his exceptionally wide and intimate knowledge of Scottish folk-lore, which has preserved a surprisingly large part of the same legends, has enabled him to present the Egyptian stories with exceptional clearness and p. 111 sympathetic insight. But I refer to his book specially because he is one of the few modern writers who has made the attempt to compare the legends of Egypt, Babylonia, Crete, India and Western Europe. Hence the reader who is not familiar with the mythology of these countries will find his books particularly useful as works of reference in following the story I have to unfold: "Teutonic Myth and Legend," "Egyptian Myth and Legend," "Indian Myth and Legend," "Myths of Babylonia and Assyria" and "Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe".

111:1 See Leonard W. King, "Babylonian Religion," 1899.

111:2 For a useful collection of data see A. B. Cook, "Zeus".

111:3 Albert J. Carnoy, "Iranian Views of Origins in connexion with Similar Babylonian Beliefs," Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. xxxvi., 1916, pp. 300-20; and "The Moral Deities of Iran and India and their Origins," The American Journal of Theology, vol. xxi., No. i., January, 1917.

111:4 Hopkins, "Religions of India".

111:5 De Groot, "The Religious System of China".

111:6 Perry, "The Megalithic Culture of Indonesia," Manchester, 1918.

111:7 T H. Beuchat, "Manuel d’ Archéologie Américaine," Paris, 1912; T. A. Joyce, "Mexican Archæology," and especially the memoir by Seler on the "Codex Vaticanus" and his articles in the Zeitschrift für Ethnologie and elsewhere.

111:8 I.e. the offspring of the Great Mother of gods and men, Hathor, the "Eye of Re".

112:1 That is, Hathor, who as the moon is the "Eye of Re".

112:2 Elsewhere in these pages I have used the more generally adopted spelling "Sekhet".

112:3 Mr. F. Ll. Griffith tells me that the translation "flooding the land" is erroneous and misleading. Comparison of the whole series of stories, however, suggests that the amount of blood shed rapidly increased in the development of the narrative: at first the blood of a single victim; then the blood of mankind; then 7000 jars of a substitute for blood; then the red inundation of the Nile.

112:4 This version I have quoted mainly from Erman, op. cit., pp. 267-9, but with certain alterations which I shall mention later. In another version of the legend wine replaces the beer and is made out of "the blood of those who formerly fought against the gods," cf. Plutarch, De Iside (ed. Parthey) 6.

113:1 It is still the custom in many places, and among them especially the regions near the headwaters of the Nile itself, to regard the king or rain-maker as the impersonation of the life-giving properties of water and the source of all fertility. When his own vitality shows signs of failing he is killed, so as not to endanger the fruitfulness of the community by allowing one who is weak in life-giving powers to control its destinies. Much of the evidence relating to these matters has been collected by Sir James Frazer in "The Dying God," 1911, who quotes from Dr. Seligman the following account of the Dinka "Osiris":

"While the mighty spirit Lerpiu is supposed to be embodied in the rain-maker, it is also thought to inhabit a certain hut which serves as a shrine. In front of the hut stands a post to which are fastened the horns of many bullocks that have been sacrificed to Lerpiu; and in the hut is kept a very sacred spear which bears the name of Lerpiu and is said to have fallen from heaven six generations ago. As fallen stars are also called Lerpiu, we may suspect that an intimate connexion is supposed to exist between meteorites and the spirit which animates the rain-maker" (Frazer, op. cit., p. 32). Here then we have a house of the dead inhabited by Lerpiu, who can also enter the body of the rain-maker and animate him, as well as the ancient spear and the falling stars, which are also animate forms of the same god, who obviously is the homologue of Osiris, and is identified with the spear and the falling stars.

In spring when the April moon is a few days old bullocks are sacrificed to Lerpiu. "Two bullocks are led twice round the shrine and afterwards tied by the rain-maker to the post in front of it. Then the drums beat and the people, old and young, men and women, dance round the shrine and sing, while the beasts are being sacrificed, 'Lerpiu, our ancestor, we have brought you a sacrifice. Be pleased to cause rain to fall.' The blood of the bullocks is collected in a gourd, boiled in a pot on the fire, and eaten by the old and important people of the clan. The horns of the animals are attached to the post in front of the shrine" (pp. 32 and 33).

114:1 In Northern Nigeria an official who bore the title of Killer of the Elephant throttled the king "as soon as he showed signs of failing health or growing infirmity". The king-elect was afterwards conducted to the centre of the town, called Head of the Elephant, where he was made to lie down on a bed. Then a black ox was slaughtered and its blood allowed to pour all over his body. Next the ox was flayed, and the remains of the dead king, which had been disembowelled and smoked for seven days over a slow fire, were wrapped up in the hide and dragged along to the place of burial, where they were interred in a circular pit" (Frazer, op. cit., p. 35).

116:1 "Gods of the Egyptians," vol. i., p. 392.

116:2 The eye of the sun-god, which was subsequently called the eye of Horus and identified with the Uræus-snake on the forehead of Re and of the Pharaohs, the earthly representatives of Re, finally becoming synonymous with the crown of Lower Egypt, was a mighty goddess, Uto or Buto by name" (Alan Gardiner, Article "Magic (Egyptian)" in Hastings’ Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, p. 268, quoting Sethe.

116:3 "For an account of the distribution of this story see E. Sidney Hartland, "The Legend of Perseus"; also W. J. Perry, "The Megalithic Culture of Indonesia".

117:1 The original "boat of the sky" was the crescent moon, which, from its likeness to the earliest form of Nile boat, was regarded as the vessel in which the moon (seen as a faint object upon the crescent), or the goddess who was supposed to be personified in the moon, travelled across the waters of the heavens. But as this "boat" was obviously part of the moon itself, it also was regarded as an animate form of the goddess, the "Eye of Re". When the Sun, as the other "Eye," assumed the chief rôle, Re was supposed to traverse the heavens in his own "boat," which was also brought into relationship with the actual boat used in the Osirian burial ritual.

The custom of employing the name "dragon" in reference to a boat is found in places as far apart as Scandinavia and China. It is the direct outcome of these identifications of the sun and moon with a boat animated by the respective deities. In India the Makara, the prototype of the dragon, was sometimes represented as a boat which was looked upon as the fish-avatar of Vishnu, Buddha or some other deity.

118:1 This is an instance of the well-known tendency of the human mind to blend numbers of different incidents into one story. An episode of one experience, having been transferred to an earlier one, becomes rationalized in adaptation to its different environment. This process of psychological transference is the explanation of the reference to Elephantine as the source of the d’d’, and has no relation to actuality. The naïve efforts of Brugsch and Gauthier to study the natural products of Elephantine for the purpose of identifying d’d’ were therefore wholly misplaced.

119:1 In Hartland's "Legend of Perseus" a collection of variants of this story will be found.

120:1 In the version I have quoted from Erman he refers to "the god Sektet".

120:2 Op. cit., supra.