|

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

The historic relationship between Europe and the Church is a relationship that has shaped the history of the Western World.

Europe stands at a momentous crossroads. Events taking shape there will radically change the face of the continent and world.

To properly understand today's news and the events that lie ahead, a grasp of the sweep of European history is essential.

Only within an historical context can the events of our time be fully appreciated - which is why this

narrative series is written

in the historic present to give the reader a sense of being on the scene as momentous events unfold on the stage of history.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For six days and nights the great fire races out of control through the most

populous districts of the imperial city. In its fury, the blaze reduces half the

metropolis to ashes. Many of the architectural glories of ancient Rome are

devoured in the flames. Thousands of terror-stricken Romans are made homeless,

all their wordily possessions are lost.

From atop his palace roof, the Emperor Nero views the awesome panorama.

Some Romans suspect the truth. They believe that Nero — inhuman, maniacal,

insane — has personally triggered the conflagration. Fancying himself a great

builder, he desires to erase the old Rome that he might have the glory of

founding a new and grander city — Nero's Rome!

A rumor begins to circulate that the fire was contrived by the emperor

himself. Nero fears for his safety. He must find someone to bear the

blame — and quickly.

To divert suspicion away from himself, Nero lays the guilt at the door of the

new religious group — the Christians of Rome. It is the logical choice.

Christians are already despised and distrusted by many. They spurn the worship

of the old Roman gods and "treasonably" refuse to give divine honors to the

emperor. Their preaching of a new King sounds like revolution.

They have no influence, no power — the perfect scape goats.

Nero orders their punishment. The bloodbath begins. The emperor inflicts on

the falsely accused Christians horrible tortures and executions. Some are nailed

to crosses; others are covered with animal skins and torn apart by wild dogs in

the Circus Maximus; still others are nailed to stakes and set ablaze as

illumination for Nero's garden parties. For years the persecution rages. It is a

perpetual open season on Christians. Among those imprisoned and brought to trial

by Nero is a man who has been instrumental in establishing the fledgling Church

of God at Rome — Paul, the apostle to the Greek-speaking gentiles.

While Rome burns, the insane Emperor Nero plays his musical instrument.

He is suspected of poisoning his younger step-brother, of having his mother killed,

and of kicking his pregnant wife to death in a furious rage.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For many years Paul had warned the churches of impending persecutions. He had

reminded them of Jesus' own words to his disciples: "If they have persecuted me,

they will also persecute you." Paul had assured them that "all that will live

godly in Christ Jesus shall suffer persecution" (II. Tim. 3:12). The world, he

had told them, would not be an easy place for Christians. Paul, himself, had

endured much suffering and persecution during the course of his long ministry.

For more than two decades he had persevered in preaching the gospel of the

coming kingdom of God through many of the provinces of the Roman Empire. Now, at

last, his sufferings are nearing an end.

Nero sends his servants to bring Paul word of his impending death. Shortly

afterward, soldiers arrive and lead him out of the city to the place of

execution. Paul prays, then give his neck to the sword. He is buried on the

Ostian Way. The year is A.D. 68; it is early summer .Most of the remaining

elders and members of the congregation at Rome are also martyred in the Neronian

persecution. Peter — chief among the original twelve apostles — also meets his

end in A.D. 68. He is condemned to death — as Jesus himself had foretold many

years earlier (John 21:18-19)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Unfortunately, the headquarters church in Jerusalem — towards which

Christians look for truth and for leadership — is in no position to render

effective assistance to the persecuted Christians of Rome. It, too, is caught in

the midst of upheaval, stemming from the Jewish wars with Rome. In A.D. 66, the

oppressed Jews of Palestine erupt into general revolt — defying the military might

of the Roman Empire! Heeding Jesus' warning (Luke 21:20-21) the Christians of

Judea flee to the hills .Later, in the spring of A.D. 69, the Roman general

Titus finally sweeps from east of Jordan into Judea with his legions. The

Christians escape impending calamity in the hills by journeying northeast to the

out-of-the-way city of Pella, in the Gilead mountains east of the Jordan River.

It is now A.D. 70. Titus conquers Jerusalem. He burns the Temple to the ground

and tears down its foundations. The city is laid waste. Some 600,000 Jews are

slaughtered and multiple thousands of others are sold into slavery. It is a time

of unparalleled calamity!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Amid all the upheaval in Rome, Judea and elsewhere in the Empire, what is the

mood of the Christian community? What thoughts course through the minds of

Christians at this time? Though many are suffering — uprooted from homes,

imprisoned, tortured, bereaved of family and friends — the prevailing spirit among

Christians is one of hope and anticipation.

Christians are sustained by the knowledge that Jesus and the prophets of old

had foretold these tumultuous events — and their glorious outcome. As events swirl

around them they watch with breathless expectations. They take hope in the great

picture laid out by Jesus from the beginning of his earthly ministry — the return

of Jesus Christ and the reestablishment of the kingdom of God! As Mark records:

"Now after that John was put in prison. Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the

gospel [good news] of the kingdom of God, and saying, The time is fulfilled, and

the kingdom of God is at hand: repent ye, and believe the gospel." (Mark 1:14-15)

Everywhere Jesus went, he focused on this major theme — the good news of the

coming of the kingdom of God. The twelve disciples were sent out to preach the

same message (Luke 9:1-2). The apostle Paul also preached the kingdom of God.

(Acts 19:8; 20:25; 28:23, 31). Christians — in that first century — are in no doubt

as to what that kingdom is. It is a literal kingdom — a real government, with a

King, and laws and subjects — destined to rule over the earth. It is the

government of God, supplanting the government of man!

Christians rehearse and discuss among themselves the many prophecies about

this coming government. By now, they know the passage by heart. The prophet

Daniel, for example, had written of a successions of world-ruling governments

through the ages (Daniel 2) — four universal world-empires: Babylon,

Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome. Daniel declared that after the demise of these earthly kingdoms,

"the God of heaven [shall] set up a kingdom, which shall never

be destroyed....but it shall break in pieces and consume all these kingdoms, and

it shall stand for ever." (Dan. 2:44)

This kingdom will rule over the nations. It will "break in pieces and

consume" the Roman Empire — surely very soon, Christians feel! Soon the swords

and spears spilling blood across the vast territories of the Empire would be

beaten into plowshares and pruning hooks, as Isaiah had prophesied (Isa. 2:4).

Jesus would return and "the government shall be upon his shoulders" (Isa. 9:6)

For more than four millennia the righteous ancients had looked for the triumph

of this kingdom. Now, with Jerusalem the focus of world events in A.D. 66-70,

surely, it is about to arrive!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

During the days of Jesus' earthly ministry, some had thought he would

establish the kingdom of God then and there. Because, they thought that the

kingdom of God should immediately appear. Jesus had told his disciples the

parable of the nobleman who went on a journey into a far country "to receive for

himself a kingdom, and to return" (Luke 19:11-12) As Jesus later told Pilate, he

was born to be king. But, his kingdom was not of this world (age) (John 18:36).

He would return at a later time to establish his kingdom and sward his servants.

His disciples no more understood that than did Pilate.

After his crucifixion and resurrection, Jesus' disciples again asked him,

"Lord, wilt thou at this time restore again the kingdom to Israel?" (Acts 1:6)

Jesus told them that it was not for them to know the times or the seasons (verse

7). They found that hard to comprehend. But Jesus, nevertheless, commissioned

them to "be witnesses unto me....unto the uttermost part of the earth" (Acts. 1:8).

For nearly four decades they had preached the gospel throughout the Roma

world and beyond. Now, tumultuous events signal a change in world affairs. Signs

of the end of the age — given by Jesus in the Olivet prophecy (Matthew

24) — seems to become increasingly evident of the world scene.

Rome, with civil war in A.D. 69, appears to be on a fast road to destruction.

Wars, moral decay, economic crisis, political turmoil, social upheaval,

religious confusion, natural disasters — all these signs are here. The very

fabric of Roman society is disintegrating It is a rotten and a degraded world.

Surely, Jesus will soon come to correct all that! That the Roman Empire is the

fourth "beast" of Daniel's prophecy (Daniel 7) is clear to Christians. With that

fourth kingdom in the throes of revolution, God's kingdom surely will come soon!

Amid horrendous persecutions, martyrdoms and national upheavals, they wait for

their change from material to spirit (I Cor. 15:50-53) and their reward of

positions of authority and rulership in God's .kingdom (Luke 19:17-19). "I will

come again." said Jesus (John 14:3). Christians pray, "Thy kingdom come."

They wait. And wait. But, it doesn't happen.

Throngs eager to be entertained fill the Circus Maximus in Rome.

(click to enlarge) |

Decadent Romans eat and drink while observing

close at hand the life and death drama of the chariot races.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

When Jesus does not return at the height and in the aftermath — of the

cataclysmic events of A.D. 66-70, the shock is great. Many Christians are

puzzled, disturbed, demoralized. It is a mystery — an enigma. What has "gone

wrong?" The church is tested. Many face agonizing decisions. Many begin to doubt,

and question.

The apostle Paul had once faced this issue. He had long expected Jesus'

return in his own lifetime. In A.D. 50, he had written to the Thessalonians of

"we which are alive and remain unto the coming of the Lord...." (I Thess.

4:15). Five years later, in a letter to the Corinthians, he had written that "we

shall not all sleep [died]" before Jesus' coming (I Cor. 15:51). But, in a

letter to Timothy in the days just before his death, Paul clearly sees a

different picture. He writes of the "last days" in a future context. (II Tim.

3:1-2.) He declares: "I have fought a good fight, I have finished my course...."

(4:7). He speaks of receiving his reward at some future time (4:8). Unlike Paul, however, many Christians become

disheartened and discouraged. Their hopes are shattered. "Where is the promise

of his coming?" many complain.

But some Christians understand. They realize that God intends that they face

this question, to see how they will react. They wait and wait patiently,

continuing in well-doing. They remember the words of Jesus,

"Watch therefore: for ye know not what hour your Lord doth come....for in such an hour as ye think

not the Son of man cometh." (Matt. 24:42, 44)

It would be those who "endure unto

the end" — whenever that was — who would be saved (Matt. 24:13)

Some Christians — misunderstanding the final verses of the Gospel of

John — believe that Jesus will yet return in the apostle John's lifetime (John

21:20-23). As John grows progressively older — outliving his

contemporaries — many see support for this view. They still wait for Jesus'

return in their generation. They wait.

But others are not so patient. They are restless, uneasy. They begin to look

for other answers .Their eyes begin to turn from the vision of God's kingdom and

the true purpose of life. They lose the true sense of urgency they once had.

They begin to stray from the straight path. They become confused — and vulnerable.

Until the "disappointment," false teachers had not made significant headway

among Christians. Christians expected Jesus' return at any time — they had to be

faithful and ready at any moment! But now a large segment of the Christian

community grows more receptive to "innovations" in doctrine. The ground is now

ready to receive the evil seeds of heresy!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Following the martyrdom of many of their faithful leaders, many Christians

fall victim to error. Confused and disheartened, they become easy prey for

wolves.

False teachers are nothing new to the Church. The crisis has been a long time

in the making. As early as A.D. 50, Paul had declared to the Thessalonians that

a conspiracy to supplant the truth was already under way. "For the mystery of

iniquity doth ALREADY work," he had written to them (II Thess. 2:7) Paul also

warned the Galatians that some were perverting the gospel of Christ, trying to

stamp .out the preaching of the grue gospel of the kingdom of God that Jesus

preached (Gal. 1:6-7) He told the Corinthians that some were beginning to preach

"another Jesus" and "another gospel" (II Cor. 11:4) He branded them

"false apostles" and ministers of Satan (verses 13-15.)

Paul had often reminded the churches of the word of Jesus, that MANY would

come in his name, proclaiming that Jesus was Christ, yet, deceiving MANY (Matt.

24:4-5, 11) The MANY — not the few — would be lead down the paths of error,

deceived by a counterfeit faith masquerading as Christianity. The prophecy now

comes to .pass. The situation grows increasingly acute. The introduction of

false doctrines by clever teachers divides the beleaguered Christian community.

It is split into contending factions, rent asunder by heresy and false

teachings!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Unknown to many, this havoc in the Church represents a posthumous victory for a man who had sown the first seeds of the problem decades earlier. Notice what had occurred:

A sorcerer named Simon, from Samaria (the one-time capital of the house of

Israel), had appeared in Rome in A.D. 45, during the days of Claudius Caesar.

This Simon was high priest of the Babylonian-Samaritan mystery religion (Rev.

17:5), brought to Samaria by the Assyrians after the captivity of the house of

Israel (II Kings 17:24). Simon made a great impression in Rome with his demonic

miracle-working — so much so that he was deified as a god by many of its

superstitutious citizens.

Earlier, in A.D. 33, while still in Samaria, Simon (often known as Simon

Magus — "The Magician") had been impressed by the power of Christianity. He had

been baptized, without adequate counseling, by Philip the deacon. Yet, Simon, in

his heart, had not been willing to lay aside the prestige and influence he had

as a magician over the Samaritans. So he asked for the office of an apostle and

offered a sum of money to buy it. Jesus' chief apostle, Simon Peter, sternly

rebuked Simon the magician, told him to change his biter attitude and banned him

from all fellowship in hope of future repentance. (Acts 8)

(His offer of money to the Apostles, to enable him to confer the gift of the Holy Ghost, has branded his name for ever through the use of the word "SIMONY".)

Traveling to Rome years later, Simon conspired to sow the seeds of division

in the rapidly growing Christian churches of the West. His goal: to gain a

personal following for himself. He seized upon the name of Christ as a clock for

his teachings, which were a mixture of Babylonian paganism, Judaism and

Christianity

He appropriated a Christian vocabulary to give a surface appearance to

Christianity to his insidious dogmas.

By the time of his death, Simon had not fully succeeded in seducing the

Christian community at large. But there were those who were attracted to certain

of his compromising syncretistic ideas. Slipping unobtrusively into the Church

of God, they subtly introduced elements of Simon's teachings. Many fall victim

to these false doctrines. Luke, writing the book of Acts in A.D. 62, exposes

Simon in an attempt to stem his growing influence.

With Simon now exposed, those who had crept into Church fellowship, and who

thought in part as he did, disassociate themselves from his name yet continue to

promote his errors.. They are no longer known, or recognized as Simonians — but

they hold the same doctrine! They assume the outward appearance of being

Christians — preaching about the person of Christ — yet deny Christ's message,

the gospel of the coming kingdom of God.

A few years after Luke exposes Simon Magus, Jude writes of these Simonians as

"certain men crept in unawares" (Jude, verse 4) and exhorts Christians to

"earnestly contend for the faith which was once delivered." (Verse 3) Also — as

Paul had earlier prophesied (Acts 20:29-30) — some even within the Church of God

departed from the original faith and because of personal vanity, a love of money

or because of personal hurts ,begin to draw disciples away after themselves.

Heresies are rife! Sometimes, they are recognized, but often they are

disguised and go undetected. Error creeps inn slowly and imperceptibly,

gradually undermining the very truths of the Church that Jesus founded.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

There remains one last obstacle to the complete triumph of heresy — the

apostle John. is the last survivor of the original twelve apostles. He works

tirelessly to stem the tide of error and apostasy.

Writing early in the last quarter of the first century, John declares that

"many deceivers are entered into the world" (II John 7). He writes of the many

who have already left the fellowship of the Church. "They went out from us, but

they were not of us" — (I John 2:19) He revels that some apostate church leaders

are even casting true Christians out of the church! (III John 9-10) During the

persecutions of the Roman emperor Domitian, John is banished to the Aegean

island of Patmos. Thedre he receives an astounding revelation.

In a series of visions, John is carried forward into the future, to the "day

of the Lord" — a time when God will supernaturally intervene in world affairs,

sending plagues upon the unrighteous and sinning nations of earth. And a time

that will climax in the glorious Second Coming of Jesus Christ! The picture laid

out in vision to John represents another major shock for the first-century

Church. Here are astounding, almost unbelievable revelations! Images of

multithreaded beasts, of great armies, of strange new weapons, of devastating

plagues and natural disasters! What does it all mean?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

After publication of the Revelation, those with understanding begin to grasp

the message. It becomes clear to them that Jesus' coming is not as imminent as

once believed. Whole sections of the book of Daniel, previously obscure, now

become clearer. These great events revealed to John by Jesus Christ will not

occur overnight. Great periods of time appear to be implied — centuries,

possibly even millennia!

Some few begin to see the teachings of Jesus in a new light. He had stated in

his Olivet prophecy (Matt. 24:22) that "except those [last] days be shortened,

there should NO FLESH be saved...." Many had wondered about this statement. They

could not understand how there could even be enough swords, spears, and

arrows — and men to use them — to even threaten the GLOBAL annihilation of all

mankind.

Now, John's vision provided an answer. There would one day come a time when

never-before-heard-of superweapons — described by John in strange symbolic

language — would make total annihilation possible! ONE DAY.....but not now.

There will yet come a future crisis over Jerusalem, many also realize. There

will come a time when Jerusalem will again compassed with armies (Luke 21:20)

trigger a crisis even greater than that of A.D. 66-70.

Some also begin to realize that Jesus' commission to his disciples to take

the gospel "to the uttermost parts of the earth" might be meant literally! Jesus had prophesied that

"this gospel of the kingdom shall be preached in all the

world for a witness unto all nations; and THEN shall the end come." (Matt. 24-14)

And that worldwide undertaking would require time — a great deal of

time! Some few begin to see clearly. But many cannot handle this new truth. Some

even begin to teach that the kingdom is already here — that it is the Church

itself, or in the hearts of Christians.

John is released from imprisonment in A.D. 96. In his remaining days he and

faithful disciples strive to keep the Church true to the faith as he was

personally instructed in it by Jesus himself. The First Century closes with the

death of the aged apostle John in the city of Ephesus.

Jesus has not yet come. Some continue to wait. Others within and without the

fellowship of the true Church of God.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The civil turmoil within the Roman Empire temporarily ceases.

But the hopes of many Christians are shattered. Instead of being

delivered, Christians continue to suffer persecution as a result of Emperor

Nero's example. Each day brings fresh news of the imprisonment or martyrdom of

relatives and friends.

Many Christians are confused. They thought the signs of the "end of the age" —

including Roman armies surrounding Jerusalem (Luke 21:20) — had all been

there. Events had appeared to be moving swiftly toward the anxiously awaited

climax — the triumphal return of Jesus Christ as King of kings. But Jesus has not

returned. He should have come, many say to themselves. But he hasn't. Divisions

set in among Christians. Then comes the Revelation of Jesus Christ to John, the

last surviving apostle. It explains that what occurred in A.D. 66 to 70 was only

a forerunner of a final crisis over Jerusalem at the end of this age of human

self-rule. The end is not now.

In disappointment or in impatience, many who call themselves Christians

begin to stray from the truth — or to renounce Christianity altogether. Those who

stray become susceptible to "innovations" in doctrine. Heresy is rife.

Congregations become divided by doctrinal differences even though they all call

themselves the Churches of God. Some begin to express doubts about the book of

Revelation, and press forward their own doctrinal views.

The apostasy foretold by the apostles moves ahead. Only the aged

apostle John stands in the way. The more than three decades since the death of

Peter and of Paul in AD. 68 have been spent under the sole apostolic leadership

of John. The churches directly supervised by him and faithful elders assisting

him have held firm to the government of God over the Church and to God's

revealed truth. But now comes another shock. The apostle John dies in Ephesus.

At once, self-seeking contenders for authority grasp for power over the

churches. A full-scale rebellion breaks out against the authority of God's

government as it has been administered by the apostles and then solely by the

apostle John.

Many lose sight of where and with whom God has been working. They turn

from the teachings of John and faithful disciples to follow others who claim to

have authority and preeminence and who call themselves God's ministers. They

become the mainstream of professing Christianity.

But some remain faithful even though now separated from the mainstream

of Christianity. They hold fast to sound doctrine and resist the forces of the

invisible Satan who deceives the whole world. They continue to believe the good

news of the coming restoration of the government of God over the earth. They

continue to wait for Jesus to return with powçr to force world peace.

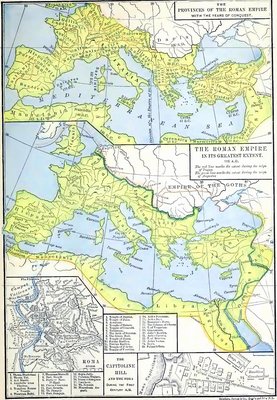

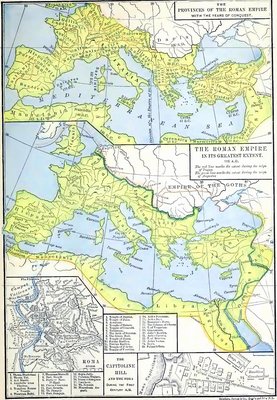

Provinces of the Roman Empire with the Years of Conquest.

The Roman Empire in its Greatest Extent 116 A.D.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Regardless of their doctrinal differences whether apostate or faithful — all who call themselves Christian continue to suffer persecution. The

polytheistic Romans are not by nature intolerant in religion. They permit many

different forms of belief and worship . They have even incorporated elements of

the religions of conquered peoples into their own.

But the various sects of Christianity pose a special problem. Adherents

to the various pagan religions readily accommodate themselves to the deification

of the emperor and the insistence that all loyal citizens sacrifice at his

altar. But this kind of "patriotism" goes far beyond what is possible for any

Christians. So they are punished not because they are Christians per se, but

because they are "disloyal."

Nero, the first of the persecuting emperors, had set a cruel precedent.

During the next 250 years, 10 major persecutions are unleashed upon

Christianity. About A.D. 95, Emperor Domitian — the younger son of Vespasian and

brother of Titus, destroyer of Jerusalem — launches a short but severe

persecution on Christians. Thousands are slain in his reign of terror.

In AD. 98, Marcus Ulpius Trajanus — commonly known as Trajan — is elected

emperor by the Roman senate. In his eyes, Christianity is opposed to the state

religion and therefore sacrilegious and punishable. Among the many who die

during his reign is the influential theologian Ignatius, bishop of Antioch in

Syria, who is thrown to the lions in the Roman arena in AD. 110.

Trajan's successors Hadrian (117-138) and Antoninus Pius (138-161)

continue the carnage. Among those to suffer martyrdom during the latter's reign

is the illustrious Polycarp, elder at Smyrna and the leading Christian figure

in Asia Minor.

With the accession of Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161-180), the Empire

suddenly finds itself disrupted by wars, rebellions, floods pestilence and

famine. As often happens in times of great disaster the ignorant populace seeks

to throw the blame for these calamities on an unpopular class in this case, the

various sects of Christians.

The strong outcry raised against what the world sees as Christianity

leaves Marcus Aurelius no choice. In troubled times as these, there can be only

one loyalty to the emperor . He orders the laws to be enforced. The resulting

persecution — the severest since Nero's day — brings a horrible death to thousands

of Christians. Among them is the scholar Justin Martyr, who is put to death at

Rome.

The Roman emperors Septimius Severus (193-211) and Maximin (235-238)

continue the persecutions. Hunted as outlaws, thousands of Christians are burned

at the stake, crucified or beheaded. Emperor Decius (249-251) determines to

completely eradicate Christianity. Blood flows in frightful massacres throughout

the Empire . A subsequent persecution under Valerian (253-260) goes even

further in its severity.

But the persecution inaugurated by Diocletian (284-305) surpasses them

all in violence. This 10th persecution is a systematic attempt to wipe the name

of Christ from the earth! Diocletian's violence towards the Christian sects is

unparalleled in history. An edict requiring uniformity of worship is issued in

A.D. 303. By refusing to pay homage to the image of the emperor, all Christians

in the realm become outlaws. Their public and private possessions are taken from

them, their assemblies are prohibited, their churches are torn down, their

sacred writings are destroyed.

The victims of death and torture number into the tens — even hundreds — of

thousands. Every means is devised to exterminate the obstinate religion. Coins

are struck commemorating the "annihilation of the Christians." Only in the

extreme western portion of the Empire do Christians escape. Constantius Chlorus

Roman military ruler of Gaul, Spain, Britain and the Rhine frontier — prevents the

execution of the edict in the regions under his rule . He protects the

Christians, whose general virtues he esteems.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Diocletian's reign also brings a development of great historic

importance within the political realm. Diocletian realizes the Empire is too

large to be administered by a single man. For purposes of better government of

so vast an empire, Diocletian voluntarily divides the power and responsibility

of his office, associating with himself his friend Maximian as co-emperor.

The two divide the Empire. Diocletian takes the East, with his capital

at Nicomedia in Asia Minor. Maximian takes the West and establishes his

headquarters at Milan in northern Italy. Each of these two Augusti or emperors

then selects an assistant with the title of Caesar. These deputy emperors are to

succeed them, and designate new Caesars in turn. The Caesars chosen by

Diocletian and Maximian are Galerius and Constantius Chlorus. They are to

command the armies of the frontiers.

After a severe illness, Diocletian abdicates his power on May 1, 305.

He compels his colleague Maximian to follow his example the same day. They are

succeeded by their respective deputy emperors, Galerius and Constantius. These

two former Caesars are now Augusti. Galerius rules the East; Constantius rules

the West.

When Constantius dies suddenly the next year while on expedition

against the Picts of Scotland, his troops immediately proclaim his son

Constantine as emperor. The smooth succession envisioned by Diocletian never

takes place. For the next eight years, there follows a succession of civil wars

among rival pretenders for imperial power. Constantine engages these competitors

in battle. The stage is now set for history-making events, within both the Empire

and Christianity.

Division of the Roman Empire by Diocletian in 292.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It is now 312. The persecution inaugurated by Diocletian nine years

earlier still rages. In Rome, Miltiades is bishop over the Christian groups

there.

By this time, the bishop of Rome has come to be generally acknowledged

as the leader of Christianity in the West. He is called "pope" (Latin, papa,

"father"), an ecclesiastical title long since given to many bishops.

(It will not be until the 9th century

that the title is reserved exclusively for the bishop of Rome.)

Fabianus (236-50) was the first, almost the only,

Pope whom we definitely know to have died for his faith. With a violent persecution underway, Miltiades

expects a similar fate.

It is October 28. Miltiades emerges from his small house to discover

the great Constantine standing in the Street before him! With him are guards

with drawn swords. Constantine has just defeated his brother-in-law and chief

rival Maxentius (son of the old Western emperor Maximian) at the Milvian Bridge

near Rome. Winning this key battle has secured Constantine's throne. He is now

sole emperor in the West.

But what does Constantine want of Miltiades? Does he intend to cap his

victory by personally executing the leader of Rome's Christians? The emperor

steps forward. With Miltiades' chief priest, Silvester, serving as interpreter,

Constantine begins to speak. What Miltiades hears signals

the beginning of a new era. The world will never be the same again.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Just before the battle of Milvian Bridge, Constantine had seen a

vision. In the sky appeared a flaming cross, and above it the words

In Hoc Signo Vinces ("In this sign,

conquer!"). Stirred by the vision, he ordered that the Christian symbol the

monogram XO (the superimposed Greek letters X and P. Chi and Rho, the first two letters

of the word Christos) — be inscribed upon

the standards andshields of the army. The battle was then fought in the name of

the Christian God. Constantine was victorious. Maxentius was defeated and

drowned.

The crucial victory spells not only supreme power for Constantine, but

a new era for the Church. Constantine becomes

the first Roman emperor to profess Christianity, though he delays baptism

until the end of his life. A magnificent triumphal arch is erected in his honor

in Rome. It ascribes Constantine's victory to the "inspiration of the Divinity."

Soon afterward, Constantine issues the Edict of Milan (313), granting Christians full freedom to practice their

religion. Though pagan worship is still tolerated until the end of the century,

Constantine exhorts all his subjects to follow his example and become

Christians. Constantine donates to the bishop of Rome the opulent Lateran

Palace. When Silvester is named bishop of Rome upon Miltiades' death in January,

314, he is crowned — clad in imperial raiment — as an earthly prince. The emperor

fills many chief government offices with Christians and provides assistance in

building churches.

Things have indeed changed !

For centuries persecuted by the Empire, the Christian Church has now become

allied with it! Christianity assumes an intimate relationship with the secular

power. It quickly grows to a position of great influence over the affairs of the

Empire. Christians of decades past would not have believed it. They are free

from persecution. The Emperor himself is a Christian!

It is simply "too good to be true." Yet it is true !

Many Christians puzzle over this new order of things. For nearly three

centuries they had waited for the return of Jesus Christ as deliverer. They had

waited for the fall of Rome, and the triumph of the kingdom of God. But now the

persecutions have ended. The Church holds a position of power and respect

throughout the Empire. The picture appears bright for the faith! What does it

all mean?

Christians of various persuasions see many prophecies of persecution in

the Scriptures. But nowhere do Jesus or the apostles foretell a popular growth

and universal acceptance of the Church. No prophecy says that the Church of God

will become great and powerful in this world. Yet look what has happened! How is

it to be understood? After centuries of believing that the kingdom was "not of

this world" that the world and the Church would be at odds until Jesus'

return — professing Christians now search for an explanation to the new state of

affairs.

The Emperor Views the Flaming Cross |

A Bronze Statue of Constantine Erected in 1998

on the Grounds of York Minster England.

(click to enlarge) |

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Continuing events within the Empire further fuel this reevaluation. In

321, Constantine issues an edict forbidding work on "the venerable day of the

sun" (Sunday), the day that had come to be substituted for the seventh-day

Sabbath (sunset Friday to sunset Saturday). Christians in general had hitherto

held Saturday as sacred, though in Rome and in Alexandria, Egypt, Christians had

ceased doing so. (In 365, the Council of Laodicea will formally prohibit the

keeping of the "Jewish Sabbath" by Christians.)

In 324, the Emperor formally establishes Christianity as the official

religion of the Empire . The previous year, Constantine had defeated the Eastern

Emperor and had become the sole Emperor of East and West. Thus Christianity is

now the established religion throughout the

civilized Western world! In an effort to further promote unity and

uniformity within Christianity, Constantine calls a conclave of bishops from all

parts of the Empire in 325. The council intended to settle doctrinal disputes

among Christians — is held at Nicea, in Bithynia.

The Council of Nicea confronts two major issues. It deals firstly with

a dispute over the relationship of Christ to God the Father. The dispute is

called the Arian controversy. Arius, a priest of Alexandria, has been teaching

that Christ was created, not eternal and divine like the Father. The Council

condemns him and his doctrine and exiles Arian teachers. (The movement, however,

continues strong in many areas. When Gothic and Germanic invaders are converted

to Christianity, it is frequently to the Arian form.)

The other major issue at the Council is the proper date for the

celebration of Passover. Many Christians - especially those in Asia Minor — still

commemorate Jesus' death on the 14th day of the Hebrew month Nisan - the day the

"Jewish" passover lambs had been slain. In contrast, Rome and the Western

churches emphasize the resurrection, rather than the death of Jesus. They

celebrate an annual Passover feast — but always on a Sunday.

The Council rules that the ancient Christian Passover commemorating the

death of Jesus must no longer be kept — on pain of death. The Western custom is to

be observed throughout the Empire, on the first Sunday after the full moon

following the vernal equinox. It is later to be called "Easter" when the

Germanic tribes are converted en masse to Christianity. Most Christians accept

this decree. They constitute mainstream Christianity and the world accepts them

as such. But some refuse, and flee (Rev. 12:6) into the valleys and mountains of

Europe and Asia Minor to escape persecution and death. They continue, away from

the world's view, as the true Church of God, lost in the pages of history.

The Arch of Constantine in Rome, situated between the Colosseum and the Palatine Hill,

was Erected in A.D. 312 to Celebrate his Victory over Maxentius.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

As the majority of Christians view this new unity and uniformity within

the Church and the near universality of its influence, a revolution in thinking

takes place. There is now ONE Empire, ONE Emperor, ONE Church, ONE God. Many

Christians wonder: Is it possible they have not fully understood the concept of

the kingdom of God? Is it possible that the Church itself or even the now-Christianized

Empire is the long-awaited kingdom of

God?

Or, might it be that God's kingdom is meant to be established on earth

gradually, in successive stages? Could

Constantine's edicts be the first step in this process?

This is a time of reevaluation, of deep soul-searching. Some few

declare the Church should wield no secular power — that such would be inconsistent

with the spirit of Christianity. Entangling itself with temporal affairs, they

assert, will only corrupt the Church from its true purpose. They declare that

the world is still the enemy---only

its outward tactics have changed.

But the majority feels differently. Here, they believe, is a great

opportunity to spread their Christianity throughout the Empire and beyond.

Hundreds of thousands---even millions — will be converted. The opportunity,

they say, must be seized, not shunned!

The fateful union of Church and State is thus ratified. That move shapes the

course of civilization for centuries to come.

Fragments of Constantine's huge statue were discovered in Rome in 1486.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Constantine the Great dies on May 22, 337. Water is poured on his

forehead and he is declared "baptized" on his death bed. About a quarter century

after onstantine's death, his nephew Julian (361-363) gains the throne. Julian

rejects the faith of his uncle and endeavors to revive the worship of the old

gods. His hatred of the Christians gains for him the surname "Apostate."

To spite the Christians, Julian patronizes the Jews, and even attempts

to rebuild their Temple in Jerusalem. He is thwarted, however, by "balls of

fire" issuing from the foundation, which makes it impossible for the workmen to

approach. Despite Julian's efforts, the old stories of gods and goddesses have

lost their hold on the Roman mind. After Julian is killed while invading Persia,

Christianity returns to full prominence in the Empire.

In 394, under Emperor Theodosius (378-395), the ancient gods are

formally outlawed in the Empire. Conversion to Christianity becomes compulsory.

The power of the Church in Theodosius' time is best illustrated in an incident

involving Ambrose, the archbishop of Milan. A man of savage temper, Theodosius

orders the massacre of about 7,000 people of Thessalonica, as a punishment for a

riot that had erupted there. The Thessalonians are butchered, the innocent with

the guilty — by a detachment of Gothic soldiers sent by Theodosius for that

purpose.

When the Emperor later attempts to enter the cathedral in Milan,

Ambrose meets him at the door and refuses him entrance until he publicly

confesses his guilt in the massacre . Though privately remorseful, the Emperor

is reluctant to diminish the prestige of his office by such a humiliation. But

after eight months, Theodosius the master of the civilized world — finally yields

and humbly implores pardon of Ambrose in the presence of the congregation. On

Christmas Day, A.D. 390, he is restored to the communion of the Church. The

incident emphasizes the independence of the Western Church from imperial

domination.

Theodosius is the last ruler of a united Roman Empire. At his death the

Empire is divided between his two sons Honorius (in the West) and Arcadius

(in the East). Though in theory only a division for administrative purposes, the

separation proves to be permanent. The two sections grow steadily apart, and are

never again truly united. Each goes its own way towards a separate destiny.

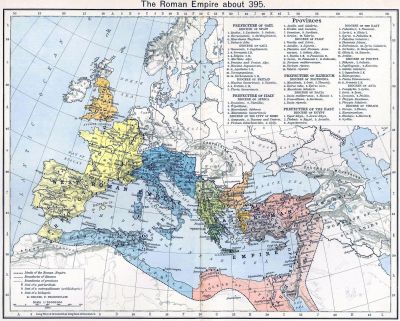

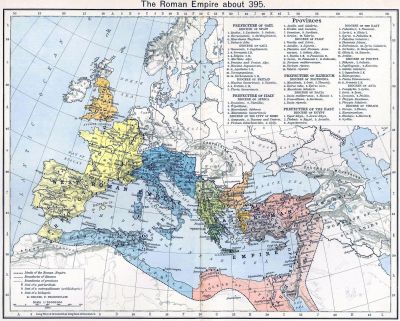

The Roman Empire Around the Year 395.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, the restless Gothic and Germanic tribes to the north grow

stronger and more threatening to the peace of the Empire. For centuries the

Romans have fought off the barbarian hordes. Now these tribes begin to move into

the Empire in force. Not all, however, have come as enemies . For decades many

tribes have been coming across the Roman frontiers peaceably, as settlers. Many

Germans are now serving in the Roman army, and some in the imperial palace

itself.

When Emperor Theodosius dies (395), one of these Germans is even named

as guardian of his young son Honorius. He is Stilicho, a "barbarian" of the

Vandal nation; son of a Vandal father and a Roman mother. A brilliant general, Stilicho repeatedly beats back attempted

invasions of Italy by various barbarian tribes. Most troublesome of all is

Alaric the Visigoth. Stilicho repels numerous assaults by Alaric into the

peninsula. But Honorius is jealous of the general who has so often saved Rome.

In August, 408, he has Stilicho assassinated. The news of his death rouses

Alaric to yet another invasion.

For a costly ransom, Alaric spares Rome in 409. But the next year he

comes again. On August 10, AD. 410, Alaric takes the "Eternal City," and for six

days Rome is given up to murder and pillage. For the first time in nearly 800

years, Rome is captured by a foreign enemy!

It is a profound shock. Many cannot believe it. When Jerome — the translator of the Bible into Latin — hears the news in Bethlehem, he writes:

"My voice is choked, and my sobs interrupt the words I write.

The city which took the whole world is herself taken. Who could

have believed that Rome, which was built upon the spoils of the

earth, would fall?"

Many bemoan the event as the fall of the Western Roman Empire. But there is still an emperor on the imperial throne. In a ceremonial way, at least,

the Empire continues.

Alaric withdraws from the city and dies soon afterward. Rome grants the

Visigoths the richest parts of Gaul as a permanent residence. By the middle of,

the 5th century, barbarian tribes are occupying most parts of the

Western Roman Empire.

Alaric and his Visigoths Enter and Plunder Rome in 410 A.D.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Of all the barbarian tribes, perhaps the non-Germanic Huns are the most

feared of all. A nomadic people moving out of Central Asia, they are led by the

famous Attila, known to the world of his time as the "Scourge of God." In 451,

Attila invades Gaul, his objective being the kingdom of the Germanic Visigoths.

The Roman General Aetius — massing the combined forces of the Western Empire and

the Visigoths holds his own against Attila near Chalons. It is called "the

battle of nations," one of the most memorable battles in the history of the

world. It is Attila's first and only setback.

Though checked, Attila's power is not destroyed. The next year (452)

Attila appears in northern Italy with a great army. Rome's defenses collapse.

The road to Rome lies open before Attila. Its citizens expect the worst. But

Rome is spared. Attila withdraws when success lies just within his grasp. The

threatened march on Rome does not take place! What has happened?

Attila had just come with his battered army from its terrible defeat at Chalons,

that it was suffering heavily from disease and weariness, and Attila was too sagacious

a commander to venture farther into Italy. He withdrew his troops,

laden with booty and ransom, from the enervating and infectious south.

The bishop of Rome at this time is a man named Leo. He has traveled

northward to the river Po to meet the mighty Attila. There is no record of the

conversation between the two. But one fact is clear. A fearless diplomat, Leo

has confronted the "Scourge of God" and won. He has somehow persuaded Attila to

abandon his quest for the Eternal City. Attila dies shortly afterward. The Huns

trouble Europe no more.

The prestige of the papacy is greatly enhanced by Leo's intervention on

behalf of Rome. As the civil government grows increasingly incapable of keeping

order, the Church begins to take its place, assuming many secular

responsibilities. History will record that it was Leo the Great who laid the

foundations of the temporal power of the popes. Leo has become the leading

figure in Italy!

In the religious sphere, Leo strongly asserts the primacy of Rome's

bishop over all other bishops. Earlier in the century, the illustrious

Augustine, bishop of Hippo in North Africa, allegedly uttered the now-famous words,

"Rome has spoken; the cause is settled." In reality, he was as stern an opponent of the Papal claim

as Basil and Cyprian were. At the Council of Chalcedon in 451, the

assembled bishops responded to Leo's pronouncements with the words: "Peter has

spoken by Leo; let him be anathema who believes otherwise." The doctrine that

papal power had been granted by Christ to Peter, and that that power was passed

on by Peter to his successors in Rome, begins to take firm root.

In June, 455, Geiseric (Genseric) — the Vandal king of North

Africa — occupies Rome. Again Leo saves the day. Leo induces Geiseric to have

mercy on the city. Geiseric consents to spare the lives of Rome's citizens,

demanding only their wealth. Leo's successful intervention further increases the

prestige and authority of the papacy, within the Empire as well as the Church.

Attila's Conquests to the Year 450.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

But the city of Rome is fast dying, and even the papacy's efforts

cannot save her. The Empire lives only in a ceremonial sense. The Western

emperors are mere puppets of the various Germanic generals. Now even the

ceremony is about to be stripped away.

It is 476. A boy-monarch sits on the throne in Rome.

His name is Romulus Augustus, but he is satirically dubbed

"Augustulus," meaning "little Augustus." By curious coincidence, he bears the

names of the founder of Rome (Romulus) and of the Empire (Augustus) — both of

which are about to fall.

The German warrior Odoacer (or Odovacar) — a Heruli chieftain ruling

over a coalition of Germanic tribes — sees no reason for carrying on the sham of

the puppet emperors any longer. On September 4, 476, he deposes Romulus

Augustulus. The long and gradual process of the fall of Rome is now complete.

The Western Empire has received a mortal wound. Rome has fallen. The

office of Emperor is vacant. There is no successor. The former mistress of the

world is the booty of barbarians. Zeno, the Eastern Emperor at Constantinople

(founded by Constantine in 327 as the new capital for the Eastern half of the

Empire), appoints Odoacer patricius ("patrician") of Italy. But in reality,

Constantinople has little power in the West. Odoacer is an independent king in

Italy.

Romulus Augustulus Giving up the Crown to Odoacer.

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

With the fall of the Western Empire, ancient history draws to a close.

A transitional period follows. Every portion of the Western Empire is occupied

and governed by kings of Germanic race. Many of these barbarian kings are, like

Odoacer, converts to Arian Christianity, opposed to the "Catholic" Christianity

of Rome.

But their kingdoms are not destined to endure. Forces are already

silently at work, forces seeking to mold out of the ruins of the old Western

Empire a revived and revitalized Roman Empire — a non-Arian Empire!

These forces will ultimately succeed in healing the deadly wound of A.D. 476 — with epoch-making consequences.

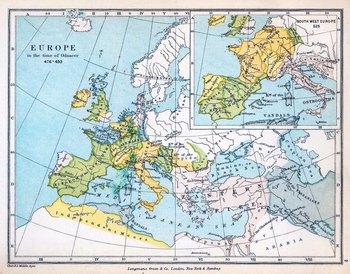

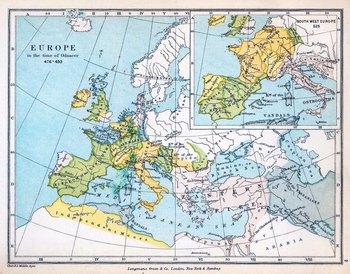

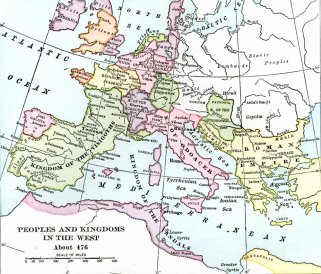

Europe in the time of Odoacer 476-493.

(click to enlarge) |

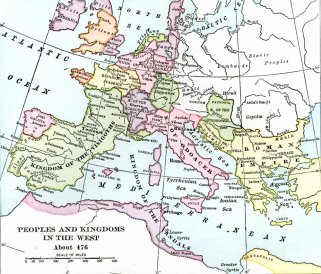

Peoples and Kingdoms in the West About 476.

(click to enlarge) |

In the public interest.

Text by: Keith W. Stump