| Family XXXVIII. ARDEINAE. HERONS. GENUS I. ARDEA, Linn. HERON. |

Next >> |

Family |

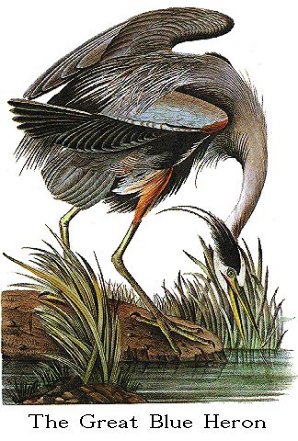

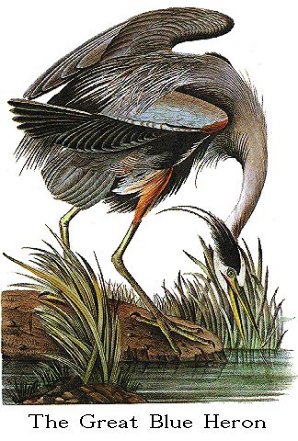

THE GREAT BLUE HERON. [Great Blue Heron (see also Great White Heron).] |

| Genus | ARDEA HERODIAS, Linn. [Ardea herodias.] |

The State of Louisiana has always been my favourite portion of the Union, although Kentucky and some other States have divided my affections; but as we

are on the banks of the fair Ohio, let us pause awhile, good reader, and watch

the Heron. In my estimation, few of our waders are more interesting than the

birds of this family. Their contours and movements are always graceful, if not

elegant. Look on the one that stands near the margin of the pure stream:--see

his reflection dipping as it were into the smooth water, the bottom of which it

might reach had it not to contend with the numerous boughs of those magnificent

trees. How calm, how silent, how grand is the scene! The tread of the tall

bird himself no one hears, so carefully does he place his foot on the moist

ground, cautiously suspending it for awhile at each step of his progress. Now

his golden eye glances over the surrounding objects, in surveying which he takes

advantage of the full stretch of his graceful neck. Satisfied that no danger is

near, he lays his head on his shoulders, allows the feathers of his breast to

droop, and patiently awaits the approach of his finned prey. You might imagine

what you see to be the statue of a bird, so motionless is it. But now, he

moves; he has taken a silent step, and with great care be advances; slowly does

he raise his head from his shoulders, and now, what a sudden start! his

formidable bill has transfixed a perch, which he beats to death on the ground.

See with what difficulty be gulps it down his capacious throat! and now his

broad wings open, and away be slowly flies to another station, or perhaps to

avoid his unwelcome observers.

The "Blue Crane" (by which name this species is generally known in the

United States) is met with in every part of the Union. Although more abundant in

the low lands of our Atlantic coast, it is not uncommon in the countries west of

the Alleghany Mountains. I have found it in every State in which I have

travelled, as well as in all our "Territories." It is well known from Louisiana

to Maine, but seldom occurs farther east than Prince Edward's Island in the Gulf

of St. Lawrence, and not a Heron of any kind did I see or hear of in

Newfoundland or Labrador. Westward, I believe, it reaches to the very bases of

the Rocky Mountains. It is a hardy bird, and bears the extremes of temperature

surprisingly, being in its tribe what the Passenger Pigeon is in the family of

Doves. During the coldest part of winter the Blue Heron is observed in the

State of Massachusetts and in Maine, spending its time in search of prey about

the warm springs and ponds which occur there in certain districts. They are not

rare in the Middle States, but more plentiful to the west and south of

Pennsylvania, which perhaps arises from the incessant war waged against them.

Extremely suspicious and shy, this bird is ever on the look-out. Its sight

is as acute as that of any Falcon, and it can hear at a considerable distance,

so that it is enabled to mark with precision the different objects it sees, and

to judge with accuracy of the sounds which it hears. Unless under very

favourable circumstances, it is almost hopeless to attempt to approach it. You

may now and then surprise one feeding under the bank of a deep creek or bayou,

or obtain a shot as he passes unawares over you on wing; but to walk up towards

one would be a fruitless adventure. I have seen many so wary, that, on seeing a

man at any distance within half a mile, they would take to wing; and the report

of a gun forces one off his grounds from a distance at which you would think be

could not be alarmed. When in close woods, however, and perched on a tree, they

can be approached with a good chance of success.

The Blue Heron feeds at all hours of the day, as well as in the dark and

dawn, and even under night, when the weather is clear, his appetite alone

determining his actions in this respect; but I am certain that when disturbed

during dark nights it feels bewildered, and alights as soon as possible. When

passing from one part of the country to another at a distance, the case is

different, and on such occasions they fly under night at a considerable height

above the trees, continuing their movements in a regular manner.

The commencement of the breeding season varies, according to the latitude,

from the beginning of March to the middle of June. In the Floridas it takes

place about the first of these periods, in the Middle Districts about the 16th

of May, and in Maine a month later. It is at the approach of this period only

that these birds associate in pairs, they being generally quite solitary at all

other times; nay, excepting during the breeding season, each individual seems to

secure for itself a certain district as a feeding ground, giving chase to every

intruder of its own species. At such times they also repose singly, for the

most part roosting on trees, although sometimes taking their station on the

ground, in the midst of a wide marsh, so that they may be secure from the

approach of man. This unsocial temper probably arises from the desire of

securing a certain abundance of food, of which each individual in fact requires

a large quantity.

The manners of this Heron are exceedingly interesting at the approach of

the breeding season, when the males begin to look for partners. About sunrise

you see a number arrive and alight either on the margin of a broad sand-bar or

on a savannah. They come from different quarters, one after another, for

several hours; and when you see forty or fifty before you, it is difficult for

you to imagine that half the number could have resided in the same district.

Yet in the Floridas I have seen hundreds thus collected in the course of a

morning. They are now in their full beauty, and no young birds seem to be among

them. The males walk about with an air of great dignity, bidding defiance to

their rivals, and the females croak to invite the males to pay their addresses

to them. The females litter their coaxing notes all at once, and as each male

evinces an equal desire to please the object of his affection, he has to

encounter the enmity of many an adversary, who, with little attention to

politeness, opens his powerful bill, throws out his whigs, and rushes with fury

on his foe. Each attack is carefully guarded against, blows are exchanged for

blows; one would think that a single well-aimed thrust might suffice to inflict

death, but the strokes are parried with as much art as an expert swordsman would

employ; and, although I have watched these birds for half an hour at a time as

they fought on the ground, I never saw one killed on such an occasion; but I

have often seen one felled and trampled upon, even after incubation had

commenced. These combats over, the males and females leave the place in pairs.

They are now mated for the season, at least I am inclined to think so, as I

never saw them assemble twice on the same ground, and they become comparatively

peaceable after pairing.

It is by no means a constant practice with this species to breed in

communities, whether large or small; for although I have seen many such

associations, I have also found many pairs breeding apart. Nor do they at all

times make choice of the trees placed in the interior of a swamp, for I have

found heronries in the pine-barrens of the Floridas, more than ten miles from

any marsh, pond, or river. I have also observed nests on the tops of the

tallest trees, while others were only a few feet above the ground: some also I

have seen on the ground itself, and many on cactuses. In the Carolinas, where

Herons of all sorts are extremely abundant, perhaps as much so as in the lower

parts of Louisiana or the Floridas, on account of the numerous reservoirs

connected with the rice plantations, and the still more numerous ditches which

intersect the rice-fields, all of which contain fish of various sorts, these

birds find it easy to procure food in great abundance. There the Blue Herons

breed in considerable numbers, and if the place they have chosen be over a

swamp, few situations can be conceived more likely to ensure their safety, for

one seldom ventures into those dismal retreats at the time when these birds

breed, the effluvia being extremely injurious to health, besides the

difficulties to be overcome in making one's way to them.

Imagine, if you can, an area of some hundred acres, overgrown with huge

cypress trees, the trunks of which, rising to a height of perhaps fifty feet

before they send off a branch, spring from the midst of the dark muddy waters.

Their broad tops, placed close together with interlaced branches, seem intent on

separating the heavens from the earth. Beneath their dark canopy scarcely a

single sunbeam ever makes its way; the mire is covered with fallen logs, on

which grow matted grasses and lichens, and the deeper parts with nympheae and

other aquatic plants. The congo snake and water-moccasin glide before you as

they seek to elude your sight, hundreds of turtles drop, as if shot, from the

floating trunks of the fallen trees, from which also the sullen alligator

plunges into the dismal pool. The air is pregnant with pestilence, but alive

with musquitoes and other insects. The croaking of the frogs, joined with the

hoarse cries of the Anhingas and the screams of the Herons, forms fit music for

such a scene. Standing knee-deep in the mire, you discharge your gun at one of

the numerous birds that are breeding high over head, when immediately such a

deafening noise arises, that, if you have a companion with you, it were quite

useless to speak to him. The frightened birds cross each other confusedly in

their flight; the young attempting to secure themselves, some of them lose their

hold, and fall into the water with a splash; a shower of leaflets whirls

downwards from the tree-tops, and you are glad to make your retreat from such a

place. Should you wish to shoot Herons, you may stand, fire, and pick up your

game as long as you please; you may obtain several species, too, for not only

does the Great Blue Heron breed there, but the White, and sometimes the Night

Heron, as well as the Anhinga, and to such places they return year after year,

unless they have been cruelly disturbed.

The nest of the Blue Heron, in whatever situation it may be placed, is

large and flat, externally composed of dry sticks, and matted with weeds and

mosses to a considerable thickness. When the trees are large and convenient,

you may see several nests on the same tree. The full complement of eggs which

these birds lay is three, and in no instance have I found more. Indeed, this is

constantly the case with all the large species with which I am acquainted, from

Ardea coerulea to Ardea occidentalis; but the smaller species lay more as they

diminish in size, the Louisiana Heron having frequently four, and the Green

Heron five, and even sometimes six. Those of the Great Blue Heron are very

small compared with the size of the bird, measuring only two and a half inches

by one and seven-twelfths; they are of a dull bluish-white, without spots,

rather rough, and of a regular oval form.

The male and the female sit alternately, receiving food from each other,

their mutual affection being as great as it is towards their young, which they

provide for so abundantly, that it is not uncommon to find the nest containing a

quantity of fish and other food, some fresh, and some in various stages of

putrefaction. As the young advance they are less frequently fed, although still

as copiously supplied whenever opportunity offers; but now and then I have

observed them, when the nests were low, standing on their haunches, with their

legs spread widely before them, and calling for food in vain. The quantity

which they require is now so great that all the exertions of the old birds

appear at times to be insufficient to satisfy their voracious appetite; and they

do not provide for themselves until fully able to fly, when their parents chase

them off, and force them to shift as they can. They are generally in good

condition when they leave the nest; but from want of experience they find it

difficult to procure as much food as they have been accustomed to, and soon

become poor. Young birds from the nest afford tolerable eating; but the flesh

of the old birds is by no means to my taste, nor so good as some epicures would

have us to believe, and I would at any time prefer that of a Crow or young

Eagle.

The principal food of the Great Blue Heron is fish of all kinds; but it

also devours frogs, lizards, snakes, and birds, as well as small quadrupeds,

such as shrews, meadow-mice, and young rats, all of which I have found in its

stomach. Aquatic insects are equally welcome to it, and it is an expert

flycatcher, striking at moths, butterflies, and libellulae, whether on the wing

or when alighted. It destroys a great number of young Marsh-Hens, Rails, and

other birds; but I never saw one catch a fiddler or a crab; and the only seeds

that I have found in its stomach were those of the great water-lily of the

Southern States. It always strikes its prey through the body, and as near the

head as possible. When the animal is strong and active, it kills it by beating

it against the ground or a rock, after which it swallows it entire. While on

the St. John's river in East Florida, I shot one of these birds, and on opening

it on board, found in its stomach a fine perch quite fresh, but of which the

head had been cut off. The fish, when cooked, I found excellent, as did

Lieutenant PIERCY and my assistant Mr. WARD. When on a visit to my friend JOHN

BULOW, I was informed by him, that although he had several times imported gold

fishes from New York, with the view of breeding them in a pond, through which

ran a fine streamlet, and which was surrounded by a wall, they all disappeared

in a few days after they were let loose. Suspecting the Heron to be the

depredator, I desired him to watch the place carefully with a gun; which was

done, and the result was, that he shot a superb specimen of the present species,

in which was found the last gold fish that remained.

In the wild state it never, I believe, eats dead fish of any sort, or

indeed any other food than that killed by itself. Now and then it strikes at a

fish so large and strong as to endanger its own life; and I once saw one on the

Florida coast, that, after striking a fish, when standing in the water to the

full length of its legs, was dragged along for several yards, now on the

surface, and again beneath. When, after a severe struggle, the Heron disengaged

itself, it appeared quite overcome, and stood still near the shore, his head

turned from the sea, as if afraid to try another such experiment. The number of

fishes, measuring five or six inches, which one of these birds devours in a day,

is surprising. Some which I kept on board the Marion would swallow, in the

space of half an hour, a bucketful of young mullets; and when fed on the flesh

of green turtles, they would eat several pounds at a meal. I have no doubt

that, in favourable circumstances, one of them could devour several hundreds of

small fishes in a day. A Heron that was caught alive on one of the Florida

keys, near Key West, looked so emaciated when it came on board, that I had it

killed to discover the cause of its miserable condition. It was an adult female

that had bred that spring; her belly was in a state of mortification, and on

opening her, we found the head of a fish measuring several inches, which, in an

undigested state, had lodged among the entrails of the poor bird. How long it

had suffered could only be guessed, but this undoubtedly was the cause of the

miserable state in which it was found.

I took a pair of young Herons of this species to Charleston. They were

nearly able to fly when caught, and were standing erect a few yards from the

nest, in which lay a putrid one that seemed to have been trampled to death by

the rest. They offered little resistance, but grunted with a rough uncouth

voice. I had them placed in a large coop, containing four individuals of the

Ardea occidentalis, who immediately attacked the newcomers in the most violent

manner, so that I was obliged to turn them loose on the deck. I had frequently

observed the great antipathy evinced by the majestic white species towards the

blue in the wild state, but was surprised to find it equally strong in young

birds which had never seen one, and were at that period smaller than the others.

All my endeavours to remove their dislike were unavailing, for when placed in a

large yard, the White Herons attacked the Blue, and kept them completely under.

The latter became much tamer, and were more attached to each other. Whenever

apiece of turtle was thrown to them, it was dexterously caught in the air and

gobbled up in an instant, and as they became more familiar, they ate bits of

biscuit, cheese, and even rhinds of bacon.

When wounded, the Great Blue Heron immediately prepares for defence, and

woe to the man or dog who incautiously comes within reach of its powerful bill,

for that instant he is sure to receive a severe wound, and the risk is so much

the greater that birds of this species commonly aim at the eye. If beaten with

a pole or long stick, they throw themselves on their back, cry aloud, and strike

with their bill and claws with great force. I have shot some on trees, which,

although quite dead, clung by their claws for a considerable time before they

fell. I have also seen the Blue Heron giving chase to a Fish Hawk, whilst the

latter was pursuing its way through the air towards a place where it could feed

on the fish which it bore in its talons. The Heron soon overtook the Hawk, and

at the very first lounge made by it, the latter dropped its quarry, when the

Heron sailed slowly towards the ground, where it no doubt found the fish. On

one occasion of this kind, the Hawk dropped the fish in the water, when the

Heron, as if vexed that it was lost to him, continued to harass the Hawk, and

forced it into the woods.

The flight of the Great Blue Heron is even, powerful, and capable of being

protracted to a great distance. On rising from the ground or on leaving its

perch, it goes off in silence with extended neck and dangling legs, for eight or

ten yards, after which it draws back its neck, extends its feet in a straight

line behind, and with easy and measured flappings continues its course, at times

flying low over the marshes, and again, as if suspecting danger, at a

considerable height over the land or the forest. It removes from one pond or

creek, or even from one marsh to another, in a direct manner, deviating only on

apprehending danger. When about to alight, it now and then sails in a circular

direction, and when near the spot it extends its legs, and keeps its wings

stretched out until it has effected a footing. The same method is employed when

it alights on a tree, where, however, it does not appear to be as much at its

ease as on the ground. When suddenly surprised by an enemy, it utters several

loud discordant notes, and mutes the moment it flies off.

This species takes three years in attaining maturity, and even after that

period it still increases in size and weight. When just hatched they have a

very uncouth appearance, the legs and neck being very long, as well as the bill.

By the end of a week the head and neck are sparingly covered with long tufts of

silky down, of a dark grey colour, and the body exhibits young feathers, the

quills large, with soft blue sheaths. The tibio-tarsal joints appear monstrous,

and at this period the bones of the leg are so soft, that one may bend them to a

considerable extent without breaking them. At the end of four weeks, the body

and wings are well covered with feathers of a dark slate-colour, broadly

margined with ferruginous, the latter colour shewing plainly on the thighs and

the flexure of the wing; the bill has grown wonderfully, the legs would not now

easily break, and the birds are able to stand erect on the nest or on the

objects near it. They are now seldom fed oftener than once a day, as if their

parents were intent on teaching them that abstinence without which it would

often be difficult for them to subsist in their after life. At the age of six

or seven weeks they fly off, and at once go in search of food, each by itself.

In the following spring, at which time they have grown much, the elongated

feathers of the breast and shoulders are seen, the males shew the commencement

of the pendent crest, and the top of the head has become white. None breed at

this age, in so far as I have been able to observe. The second spring, they

have a handsome appearance, the upper parts have become light, the black and

white marks are much purer, and some have the crest three or four inches in

length. Some breed at this age. The third spring, the Great Blue Heron is as

represented in the plate.

The males are somewhat larger than the females, but there is very little

difference between the sexes in external appearance. This species moults in the

Southern States about the beginning of May, or as soon as the young are hatched,

and one month after the pendent crest is dropped, and much of the beauty of the

bird is gone for the season. The weight of a full grown Heron of this kind,

when it is in good condition, is about eight pounds; but this varies very much

according to circumstances, and I have found some having all the appearance of

old birds that did not exceed six pounds. The stomach consists of a long bag,

thinly covered by a muscular coat, and is capable of containing several fishes

at a time. The intestine is not thicker than the quill of a Swan, and measures

from eight and a half to nine feet in length.

GREAT HERON, Ardea Herodias, Wils. Amer. Orn., vol. vii. p. 106.

ARDEA HERODIAS, Bonap. Syn., p. 304.

GRUAT HERON, Ardea Herodias, Nutt. Man., vol. ii. p. 42.

GREAT BLUE HERON, Ardea Herodias, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. iii. p. 87;vol. v. p. 599.

Male, 48, 72.

Resident from Texas to South Carolina. In spring migrates over the United

States, and along the Atlantic coast to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Breeds

everywhere. Retires southward in autumn. Common.

Adult Male, in spring.

Bill much longer than the head, straight, compressed, tapering to a point,

the mandibles nearly equal; upper mandible with the dorsal line nearly straight,

the ridge broadly convex at the base, narrowed towards the end, a groove from

the base to near the tip, beneath which the sides are convex, the edges

extremely thin and sharp, towards the end broken into irregular serratures, the

tip acute. Lower mandible with the angle extremely narrow and elongated, the

dorsal line beyond it ascending, and slightly curved, the ridge convex, the

sides flattish and ascending, the edges as in the upper, the tip acuminate.

Nostrils basal, linear, longitudinal, with a membrane above and behind.

Head of moderate size, oblong, compressed. Neck very long and slender.

Body slender and compressed; wings large. Feet very long; tibia elongated, its

lower half bare, very slender, covered all round with hexagonal scales; tarsus

elongated, thicker than the lower part of the tibia, compressed, covered

anteriorly with large scutella, excepting at the two extremities, where it is

scaly, the sides and hind part with angular scales. Toes of moderate length,

rather slender, scutellate above, reticularly granulate beneath, third toe much

longer than second and fourth, which are nearly equal, first shorter, but

strong; claws of moderate size, strong, compressed, arched, rather acute, the

thin inner edge of that of the third toe finely serrated.

Space between the bill and eye, and around the latter, bare, as is the

lower half of the tibia. Plumage soft, generally loose. Feathers of the upper

part of the head long, tapering, decurved, two of them extremely elongated; of

the back long and loose, of the rump soft and downy; scapulars with extremely

long slender rather compact points. Feathers of the fore-neck much elongated

and extremely slender, of the sides of the breast anteriorly very large, curved

and loose; of the fore part of the breast narrower and elongated, as they are

generally on the rest of the lower surface; on the tibia short. Wings large,

rounded; primaries curved, strong, broad, tapering towards the end, the outer

cut out on both margins, second and third longest; secondaries very large, broad

and rounded, extending beyond the primaries when the wing is closed. Tail of

moderate length, rounded, of twelve rather broad, rounded feathers.

Bill yellow, dusky-green above, loral and orbital spaces light green. Iris

bright yellow. Feet olivaceous, paler above the tibio-tarsal joints; claws

black. Forehead pure white; the rest of the elongated feathers bluish-black;

throat white, neck pale purplish-brown, the elongated feathers beneath

greyish-white, part of their inner webs purplish-blue. Upper parts in general

light greyish-blue, the elongated tips of the scapulars greyish-white, the edge

of the wing, some feathers at the base of the fore-neck, and the tibial

feathers, brownish-orange. The two tufts of large curved feathers on the fore

part of the breast bluish-black, some of them with a central stripe of white.

Lower surface of the wings and the sides light greyish-blue; elongated feathers

of the breast white, their inner edge black, of the abdomen chiefly black; lower

tail-coverts white, some of them with an oblique mark of black near the tip.

Length to end of tail 48 inches, to end of claws 63 inches, extent of wings

72; bill 5 1/2, gape 7 4/12; tarsus 6 1/2, middle toe and claw 5, hind toe and

claw 2 1/4, naked part of tibia 4; wings from flexure 20; tail 7.

The Female, when in full plumage, is precisely similar to the male.

On Prince Edward's Island, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, there is a fine

breeding-place of the Great Blue Heron, which is probably the most northern on

the Atlantic coast of North America. The birds there are more shy than they

usually are at the period of breeding, and in the most cowardly manner abandon

their young to the mercy of every intruder. A friend of mine who visited this

place for the purpose of procuring adult birds in their best plumage, to add to

his already extensive collection, found it extremely difficult to obtain his

object, until he at length thought of covering himself with the hide of an ox,

under the disguise of which be readily got within shot of the birds, which were

completely deceived by the stratagem.

Adult Male. The interior of the mouth is similar to that of the last

species, there being three longitudinal ridges on the upper mandible; its width

is 1 1/4 inches, but the lower mandible can be dilated to 2 1/4 inches. The

tongue is 3 1/2 inches long, trigonal, and in all respects similar to that of

Ardea occidentalis. The oesophagus is 24 inches in length, opposite the larynx

its width is 2 3/4 inches, it then gradually contracts to the distance of 7

inches, becomes 1 inch 10 twelfths in width, and so continues until it enters

the thorax, when it enlarges to 2 inches and so continues, but at the

proventriculus is 2 1/3 inches in breadth. The stomach is roundish, a little

compressed, 2 1/2 inches in diameter; its muscular coat thin, and composed of a

single series of fasciculi, its inner coat soft and smooth, but with numerous

irregular ridges. There is a roundish pyloric lobe, 9 twelfths in diameter.

The proventricular glands form a belt 1 inch 4 twelfths in width; at its upper

part are 10 longitudinal irregular series of very large mucous crypts; the right

lobe of the liver is 3 inches in length, the left 2 inches; there is a

gall-bladder of a curved form, 1 1/4 inches in length, and 6 twelfths in its

greatest breadth. The intestine is 7 feet 7 1/2 inches in length; its greatest

width, in the duodenum, is 3 1/2 twelfths, at the distance of 3 feet, it is

2 3/4 twelfths; a foot and a half farther on it is scarcely 2 1/2 twelfths; and

half a foot from the rectum it is 2 twelfths; it then slightly enlarges. The

rectum, including the cloaca, is 5 inches 9 twelfths in length; there is a

single coecum, 5 twelfths long, and 2 1/2 twelfths in width, the average width

of the rectum is 1/2 inch, and it expands into a globular cloaca 2 inches 2

twelfths in diameter. The duodenum curves at the distance of 5 inches, then

passes to the right lobe of the liver, bends backward, and is convoluted,

forming 22 turns, terminating in the rectum above the stomach.

The trachea is 21 inches in length, from 4 1/2 twelfths to 3 twelfths in

breadth, toward the lower part enlarged to 4 twelfths, finally contracted to 3

twelfths. The rings are 252, with 4 terminal dimidiate rings. The right

bronchus has 19, the left 20 half rings. The muscles are in all respects as in

Ardea occidentalis.

| Next >> |