| Family VI. HIRUNDINAE. SWALLOWS. GENUS I. HIRUNDO, Linn. SWALLOW. |

Next >> |

Family |

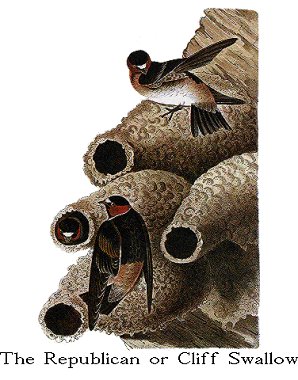

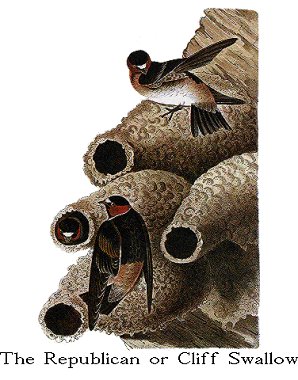

THE REPUBLICAN OR CLIFF SWALLOW. [Cliff Swallow.] |

| Genus | HIRUNDO FULVA, Vieill. [Hirundo pyrrhonota.] |

In the spring of 1815, I for the first time saw a few individuals of this

species at Henderson, on the banks of the Ohio, a hundred and twenty miles below

the Falls of that river. It was an excessively cold morning, and nearly all

were killed by the severity of the weather. I drew up a description at the

time, naming the species Hirundo republicans, the Republican Swallow, in

allusion to the mode in which the individuals belonging to it associate, for the

purpose of forming their nests and rearing their young. Unfortunately, through

the carelessness of my assistant, the specimens were lost, and I despaired for

years of meeting with others.

In the year 1819, my hopes were revived by Mr. ROBERT BEST, curator of the

Western Museum at Cincinnati, who informed me that a strange species of bird had

made its appearance in the neighbourhood, building nests in clusters, affixed to

the walls. In consequence of this information, I immediately crossed the Ohio

to Newport, in Kentucky, where he had seen many nests the preceding season; and

no sooner were we landed than the chirruping of my long-lost little strangers

saluted my ear. Numbers of them were busily engaged in repairing the damage

done to their nests by the storms of the preceding winter.

Major OLDHAM of the United States Army, then commandant of the garrison,

politely offered us the means of examining the settlement of these birds,

attached to the walls of the building under his charge. He informed us, that,

in 1815, he first saw a few of them working against the wall of the house,

immediately under the eaves and cornice; that their work was carried on rapidly

and peaceably, and that as soon as the young were able to travel, they all

departed. Since that period, they had returned every spring, and then amounted

to several hundreds. They usually appeared about the 10th of April, and

immediately began their work, which was at that moment, it being then the 20th

of that month, going on in a regular manner, against the walls of the arsenal.

They had about fifty nests quite finished, and others in progress.

About day-break they flew down to the shore of the river, one hundred yards

distant, for the muddy sand, of which the nests were constructed, and worked

with great assiduity until near the middle of the day, as if aware that the heat

of the sun was necessary to dry and harden their moist tenements. They then

ceased from labour for a few hours, amused themselves by performing aerial

evolutions, courted and caressed their mates with much affection, and snapped at

flies and other insects on the wing. They often examined their nests to see if

they were sufficiently dry, and as soon as these appeared to have acquired the

requisite firmness, they renewed their labours. Until the females began to sit,

they all roosted in the hollow limbs of the sycamores (Platanus occidentalis)

growing on the banks of the Licking river, but when incubation commenced, the

males alone resorted to the trees. A second party arrived, and were so hard

pressed for time, that they betook themselves to the holes in the wall, where

bricks had been left out for the scaffolding. These they fitted with projecting

necks, similar to those of the complete nests of the others. Their eggs were

deposited on a few bits of straw, and great caution was necessary in attempting

to procure them, as the slightest touch crumbled their frail tenement into dust.

By means of a table-spoon, I was enabled to procure many of them. Each nest

contained four eggs, which were white, with dusky spots. Only one brood is

raised in a season. The energy with which they defended their nests was truly

astonishing. Although I had taken the precaution to visit them at sun-set, when

I supposed they would all have been at rest, yet a single female happening to

give the alarm, immediately called. out the whole tribe. They snapped at my

hat, body and legs, passed between me and the nests, within an inch of my face,

twittering their rage and sorrow. They continued their attacks as I descended,

and accompanied me for some distance. Their note may be perfectly imitated by

rubbing a cork damped with spirit against the neck of a bottle.

A third party arrived a few days after, and immediately commenced building.

In one week they had completed their operations, and at the end of that time

thirty nests hung clustered like so many gourds, each having a neck two inches

long. On the 27th July, the young were able to follow their parents. They all

exhibited the white frontlet, and were scarcely distinguishable in any part of

their plumage from the old birds. On the 1st of August, they all assembled near

their nests, mounted some three hundred feet in the air, and about 10 o'clock in

the morning took their departure, flying in a loose body, in a direction due

north. They returned the same evening about dusk, and continued these

excursions, no doubt to exercise their powers, until the third, when, uttering a

farewell cry, they shaped the same course at the same hour, and finally

disappeared. Shortly after their departure, I was informed that several

hundreds of their nests were attached to the court-house at the mouth of the

Kentucky river. They had commenced building them in 1815. A person likewise

informed me, that, along the cliffs of the Kentucky, he had seen many bunches,

as he termed them, of these nests attached to the naked shelving rocks

overhanging that river.

Being extremely desirous of settling the long-agitated question respecting

the migration or supposed torpidity of Swallows, I embraced every opportunity of

examining their habits, carefully noted their arrival and disappearance, and

recorded every fact connected with their history. After some years of constant

observation and reflection, I remarked that among all the species of migratory

birds, those that remove farthest from us, depart sooner than those which retire

only to the confines of the United States; and, by a parity of reasoning, those

that remain later return earlier in the spring. These remarks were confirmed as

I advanced towards the south-west, on the approach of winter, for I there found

numbers of Warblers, Thrushes, &c. in full feather and song. It was also

remarked that the Hirundo viridis of WILSON (called by the French of Lower

Louisiana Le Petit Martinet a ventre blanc) remained about the city of New

Orleans later than any other Swallow. As immense numbers of them were seen

during the month of November, I kept a diary of the temperature from the 3d of

that month, until the arrival of Hirundo purpurea. The following notes are

taken from my journal, and as I had excellent opportunities, during a residence

of many years in that country, of visiting the lakes to which these Swallows

were said to resort, during the transient frosts, I present them with

confidence.

Nov. 11.--Weather very sharp, with a heavy white frost. Swallows in

abundance during the whole day. On inquiring of the inhabitants if this was a

usual occurrence, I was answered in the affirmative by all the French and

Spaniards. From this date to the 22nd, the thermometer averaged 65 degrees, the

weather generally a drizzly fog. Swallows playing over the city in thousands.

Nov. 25.--Thermometer this morning at 30 degrees. Ice in New Orleans a

quarter of an inch thick. The Swallows resorted to the lee of the Cypress Swamp

in the rear of the city. Thousands were flying in different flocks. Fourteen

were killed at a single shot, all in perfect plumage, and very fat. The markets

were abundantly supplied with these tender, juicy, and delicious birds. Saw

Swallows every day, but remarked them more plentiful the stronger the breeze

blew from the sea.

Jan. 14.--Thermometer 42 degrees. Weather continues drizzly. My little

favourites constantly in view.

Jan. 28.--Thermometer at 40 degrees. Having seen the Hirundo viridis

continually, and the H. purpurea or Purple Martin beginning to appear, I

discontinued my observations.

During the whole winter many of them retired to the holes about the houses,

but the greater number resorted to the lakes, and spent the night among the

branches of Myrica cerifera, the Cirier, as it is termed by the French settlers.

About sunset they began to flock together, calling to each other for that

purpose, and in a short time presented the appearance of clouds moving towards

the lakes, or the mouth of the Mississippi, as the weather and wind suited.

Their aerial evolutions before they alight, are truly beautiful. They appear at

first as if reconnoitering the place; when, suddenly throwing themselves into a

vortex of apparent confusion, they descend spirally with astonishing quickness,

and very much resemble a trombe or water-spout. When within a few feet of the

ciriers, they disperse in all directions, and settle in a few moments. Their

twittering, and the motions of their wings, are, however, heard during the whole

night. As soon as the day begins to dawn, they rise, flying low over the lakes,

almost touching the water for some time, and then rising, gradually move off in

search of food, separating in different directions. The hunters who resort to

these places destroy great numbers of them, by knocking them down with light

paddles, used in propelling their canoes.

FULVOUS or CLIFF SWALLOW, Hirundo fulva, Bonap. Amer. Orn.,

vol. i. p. 63.

HIRUNDO FULVA, Bonap. Syn., p. 64.

FULVOUS or CLIFF SWALLOW, Hirundo fulva, Nutt. Man., vol. i. p. 603.

REPUBLICAN or CLIFF SWALLOW, Aud. Orn. Biog., vol. i. p. 353;

vol. v. p. 415.

Bill shorter than in the last species; wings of the same length as the

tail, which is slightly emarginate. Upper part of head, back, and smaller

wing-coverts black, with bluish-green reflections; forehead white, generally

tinged with red; loral space and a band on the lower part of the forehead black;

chin, throat, and sides of the neck deep brownish-red; a patch of black on the

fore-neck; rump light yellowish-red; lower parts greyish-white, anteriorly

tinged with red. Female, similar to the male. Young, dark greyish-brown above,

reddish-white beneath.

Male, 5 1/2, 12. Female, 5 4/12, 12 3/4.

| Next >> |