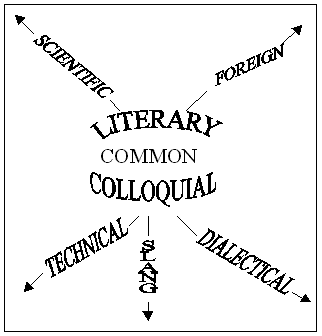

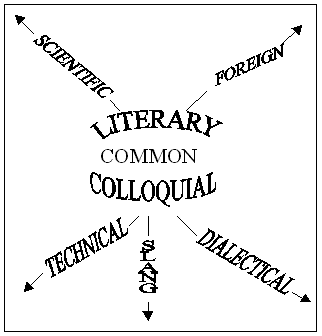

The vocabulary of a widely diffused and highly cultivated living language is not a fixed quantity circumscribed by definite limits. That vast aggregate of words and phrases which constitutes the vocabulary of English-speaking people presents, to the mind that endeavours to grasp it as a definite whole, the aspect of one of those nebulous masses familiar to the astronomer, in which a clear and unmistakable nucleus shades off on all sides, through zones of decreasing brightness, to a dim marginal film that seems to end nowhere, but to lose itself imperceptibly in the surrounding darkness. In its constitution it may be compared to one of those natural groups of the zoologist or botanist, wherein typical species forming the characteristic nucleus of the order, are linked on every side to other species, in which the typical character is less and less distinctly apparent, till it fades away in an outer fringe of aberrant forms, which merge imperceptibly in various surrounding orders, and whose own position is ambiguous and uncertain. For the convenience of classification, the naturalist may draw the line which bounds a class or order outside or inside of a particular form; but Nature has drawn it nowhere. So the English vocabulary contains a nucleus or central mass of many thousand words whose ‘Anglicity’ is unquestioned; some of then only literary, some of them only colloquial, the great majority at once literary and colloquial - they are the common words of the language. But they are linked on every side with other words which are less and less entitled to this appellation, and which pertain ever more and more distinctly to the domain of local dialect, of the slang and cant of ‘sets’ and classes, of the peculiar technicalities of trades and processes, of the scientific terminology common to all civilized nations, and of the actual languages of other lands and peoples. And there is absolutely no defining line in any direction: the circle of the English language has a well-defined centre but no discernible circumference.2 Yet practical utility has some bounds, and a dictionary has definite limits: lexicographers must, like naturalists, ‘draw the line somewhere’, in each diverging direction. They must include all the ‘common words’ of literature and conversation, and such of the scientific, technical, slang, dialectal, and foreign words as are passing into common use and approach the position or standing of ‘common words’, well knowing that the line which they draw will not satisfy all their critics. For the domain of ‘common words’ widens out in the direction of one's own reading, research, business, provincial or foreign residence, and contracts in the direction with which one has no practical connection: no one's English is all English. The lexicographer must be satisfied to exhibit the greater part of the vocabulary of each one, which will be immensely more than the whole vocabulary of any one.

In addition to, and behind, the common vocabulary, in all its diverging lines, lies an infinite number of proper or merely denotative names, outside the province of lexicography, yet touching it in thousands of points, at which these names, and still more the adjectives and verbs formed upon them, acquire more or less of connotative value. Here also limits more or less arbitrary must be assumed.

The language presents yet another undefined frontier, when it is viewed in relation to time. The living vocabulary is no more permanent in its constitution than definite in its extent. It is not today what it was a century ago, still less what it will be a century hence. Its constituent elements are in a state of slow but incessant dissolution and renovation. ‘Old words’ are ever becoming obsolete and dying out; ‘new words’ are continually pressing in. And the death of a word is not an event of which the date can be readily determined. It is a vanishing process, extending over a lengthened period, of which contemporaries never see the end. Our own words never become obsolete: it is always the words of our grandfathers that have died with them. Even after we cease to use a word, the memory of it survives, and the word itself survives as a possibility; it is only when no one is left to whom its use is still possible, that the word is wholly dead. Hence, there are many words of which it is doubtful whether they are still to be considered as part of the living language; they are alive to some speakers, and dead to others. And, on the other hand, there are many claimants to admission into the recognized vocabulary (where some of them will certainly one day be received), that are already current coin with some speakers and writers, and not yet rent coin with some speakers and writers, and not yet ‘good English’, or even not English at all, to others.

If we treat the division of words into current and obsolete as a subordinate one, and extend our idea of the language so as to include all that has been English from the beginning, or from any particular epoch, we enter upon a department of the subject of which, from the nature of the case, our exhibition must be imperfect. For the vocabulary of past times is known to us solely from its preservation in written records; the extent of our knowledge of it depends entirely upon the completeness of the records, and the completeness of our acquaintance with them. And the farther back we go, the more imperfect are the records, the smaller is the fragment of the actual vocabulary that we can recover.

Subject to the conditions which thus encompass every attempt to construct a complete English Dictionary, the present work aims at exhibiting the history and signification of the English words now in use, or known to have been in use since the middle of the twelfth century. This date has been adopted as the only natural halting-place, short of going back to the beginning, so as to include the entire Old English or ‘Anglo-Saxon’ vocabulary. To do this would have involved the inclusion of an immense number of words, not merely long obsolete but also having obsolete inflexions, and thus requiring, if dealt with at all, a treatment different from that adapted to the words which survived the twelfth century. For not only was the stream of English literature then reduced to the tiniest thread (the slender annals of the Old English or Anglo-Saxon Chronicle being for nearly a century its sole representative), but the vast majority of the ancient words that were destined not to live into modern English, comprising the entire scientific, philosophical, and poetical vocabulary of Old English, had already disappeared, and the old inflexional and grammatical system had been levelled to one so essentially modern as to require no special treatment in the Dictionary. Hence, we exclude all words that had become obsolete by 1150. But to words actually included this date has no application; their history is exhibited from their first appearance, however early.

Within these chronological limits, it is the aim of the Dictionary to deal with all the common words of speech and literature, and with all words which approach these in character; the limits being extended farther in the domain of science and philosophy, which naturally passes into that of literature, than in that of slang or cant, which touches the colloquial. In scientific and technical terminology, the aim of the first edition was to include all words English in form, except those of which an explanation would be unintelligible to any but the specialist; and such words, not English in form, as either were in general use, like hippopotamus, geranium, aluminium, focus, stratum, bronchitis, or belonged to the more familiar language of science, as Mammalia, Lepidoptera, Invertbrata. The policy governing the selection of the scientific terms included in the Supplement and added to this edition is considerably broader:

Lexicographers are now confronted with the problem of treating the vocabularies of subjects that are changing at a rate and on a scale not hitherto known. The complexity of many scientific subjects is such too that it is no longer possible to define all the terms in a manner that is comprehensible to the educated layman.3

The inclusion of Latin generic names of plants or animals depends on the quantity of evidence found for the use of the word in an English context as the name of an individual and not as the name of a genus. Names of groups above generic level are included only in their anglicized forms, when sufficient evidence for these forms could be traced: thus dytiscid has an entry but Dytiscidae has not.

Down to the fifteenth century the language existed only in dialects, all of which had a literary standing: during this period, therefore, words and forms of all dialects are admitted on an equal footing into the Dictionary. Dialectal words and forms which occur since 1500 are not admitted, except when they continue the history of a word or sense once in general use, illustrate the history of a literary word, or have themselves a certain literary currency, as in the case with many modern Scottish words.

For the purposes of treatment in this Dictionary, words and phrases are classed as: (1) main words, (2) subordinate words, (3) combinations, (4) derivatives. Main words comprise (1) single words, radical or derivative (e.g. an, ampitheatrically), (2) all those compound words (and phrases) which, from their meaning, history, or importance claim to be treated in separate articles (e.g. afternoon, almighty, almsman, air-pump, aitch-bone, ale-house, forget-me-not, Adam's apple, all fours), (3) important prefixes, suffixes, and combining forms which may give rise to large numbers of derivatives and compound words. The articles in which these are treated constitute the main articles. Subordinate words include variant and obsolete forms of main words, and such words of bad formation, doubtful existence, or alleged use, as it is deemed proper, on any ground, to record. The main and subordinate words are arranged in a single alphabetic series, distinguished simply by the treatment accorded them within the article; but articles dealing with spurious words are enclosed within square brackets. Combinations, when so simple as either to require no explanation, or to be capable of being briefly explained in connection with their cognates, are dealt with under the main words which form their first element, their treatment forming the concluding part of the main article. Similarly, such derivatives of a main word as do not by their frequency or complexity warrant a separate article are normally treated in an unnumbered paragraph following all the numbered sense sections of the main word, introduced by ‘Hence’, ‘So’, or ‘Also’. Occasionally these will be found appended to an individual, numbered sense section and treated as part of that section for the purposes of exemplification.

|

|

|