|

The History of Europe And the Church

The Relationship that Shaped the Western World

The historic relationship between Europe and the Church is a relationship that has shaped the history of the Western World.

Europe stands at a momentous crossroads. Events taking shape there will radically change the face of the continent and world.

To properly understand today's news and the events that lie ahead, a grasp of the sweep of European history is essential.

Only within an historical context can the events of our time be fully appreciated - which is why this

narrative series is written

in the historic present to give the reader a sense of being on the scene as momentous events unfold on the stage of history.

|

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

THE GREAT WAR IS OVER ! FOUR BRUTAL, BLOODY YEARS OF CONFLICT LEAVE EUROPE DEVASTATED.

The armistice is signed

on November 11, 1918. Voices around the world proclaim this was

"the war to end all wars." It is a joyous day for the victors.

But for the vanquished, it is a dark and

painful time.

The victorious Allied nations dictate a peace treaty they will

live to regret.

On June 28, 1919, the Treaty of

Versailles is signed in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles Palace, near Paris.

Germany is formally given all blame for the war. She is stripped of all her

overseas colonies, demilitarized, and strapped with near impossible reparations

payments.

The harsh terms of surrender imposed on

defeated Germany will prove to be the seeds of a greater, more horrible war to

come.

Europe in 1914

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In Italy, a troubled postwar period has begun.

Despite her membership in the Triple

Alliance, Italy had declared her neutrality on the outbreak of World War I. In

the spring of 1915, Italy joined the Allies and declared war on Germany and

Austria. Victory in 1918 fueled Italian hopes for territorial rewards.

But Italy's expectations are bitterly

disappointed. Though a victor, the country gains little from the Treaty of

Versailles. Italians complain that they have been robbed of their share of the

spoils. A sense of injury and frustration grips the country.

Among the discontented is Benito

Mussolini. Son of a poor blacksmith, Mussolini was born in 1883 in the north

Italian town of Predappio. An aggressive and ambitious child, he once declared

to his startled mother, "One day I shall make the whole earth tremble!" Formerly

a journalist and schoolmaster, Mussolini fought as a corporal in World War I. He

was seriously wounded in February 1917.

After the war, Mussolini launches a

movement that becomes, in 1921, the Fascist party. Mussolini

is il Duce "the leader" of the ultra-nationalist, anti-Communist

organization. His followers are mostly jobless, disgruntled war veterans. They adopt the black shirt as their uniform.

The Fascists derive their name from the fasces of

Imperial Rome, an ax wrapped in a bundle of elm or birch

rods symbolizing unity and power. The Fascist party adopts the ancient insignia

as its emblem.

Europe in 1919

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Italy is plagued by increasing disorder.

Unemployment, strikes, riots and general unrest tear at the fabric of society.

The government is unable to establish order. Italians look for a way out.

Mussolini — now a member of the Italian

parliament — seizes the opportunity. A gifted orator, he catches the imagination

of the crowds. Posing as a defender of law and order, he capitalizes on the

fears of middle-class Italians. Late in October 1922, the black-shirted Fascist

militia makes its dramatic march on the city of Rome. King Victor Emmanuel III.

permits them to enter the city on 1 October 28. The government is brought down.

On October 29 the king calls on Mussolini

to form a new government. Il Duce makes his entry into Rome on the 30th.

The next day he becomes the youngest prime minister in Italian history at age 39.

Mussolini's play for power has succeeded. Tired of strikes and riots, the

Italian people give him complete support. Mussolini is handed full emergency

powers. Fascism has come to power in Italy. By degrees, Mussolini tightens his

grip on the country and transforms his new government into a dictatorship.

Europe in 1921

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, in defeated Germany, a

democratic government has replaced the old Empire. It is referred to as the

Weimar Republic, because the assembly that adopted its constitution in 1919 had

met at the city of Weimar.

Many Germans cannot accept their

country's defeat. The war leaves them humiliated and disoriented. The

Weimar Republic is plagued from the start by a host of political, economic and

social problems. Germans quickly discover that it is easier to write a

democratic constitution than to make it work.

The constitution ensures the

representation of small minority parties in parliament. Innumerable separate

parties are formed. As a result, government majorities can be formed only by

coalition — temporary alliances of parties. The fragile governments thus formed

are victims of continual disunity and bickering among "partners."

Small parties often hold the balance of power, stalling and blocking legislation.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In 1921, the son of an obscure Austrian

customs official becomes president of one of Germany's many small parties — the

National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP). He is a frustrated artist

named Adolf Hitler.

As a corporal, Hitler was awarded the

coveted Iron Cross for personal bravery in World War I. Now he gathers a small

following of fellow veterans bent on overturning the humiliating Treaty of

Versailles and restoring Germany's honor. He is strongly influenced by the

career and philosophy of Benito Mussolini.

Hitler is impatient. He plots to seize

power in a coup. In November 1923, he stages the Beer Hall Putsch at Munich, an

attempt that fails to overthrow the Bavarian government. He is arrested and

imprisoned for nine months at Landsberg, where he authors an ignored volume

titled Mein Kampf ("My Struggle").

It will later become the bible of the Nazi movement.

Europe in 1923

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Back in Italy, Mussolini is endeavoring

to make Rome again the center of Western civilization.

Il Duce admires Julius Caesar above all

men. He perceives himself a modern-day Caesar, a builder of empires, a figure of

destiny. He shaves his head to make himself look more like a Caesar.

Mussolini has an intense sense of

historical mission. He is fascinated by the history of Rome. He dreams of a

modern Roman Empire, of repeating the great days of ancient Rome.

The handshake is abolished and the old

Roman salute with raised arm becomes the official greeting. Mussolini's

theatrical, gladiatorial pose becomes known world-wide. The strutting Duce is

overwhelmed by his dreams of Roman grandeur.

After Mussolini survives an assassination

attempt, the secretary of the Fascist party announces to cheering crowds:

"God has put his finger on the Duce! He is Italy's greatest son, the rightful heir of Caesar!"

Following the example of ancient Rome, some of Mussolini's Fascist

supporters even call him "divine Caesar." Ancient images fill Mussolini's

mind — and urge him relentlessly on toward his "destiny."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Italians are overwhelmingly Catholic.

Mussolini realizes that some effort must be made toward settling the long-standing "Roman Question."

Since 1870, the Popes have been in

self-imposed exile in protest against the usurpation of Papal territory by the

forces of King Victor Emmanuel II. The impasse between Italy and the Vatican

persists.

Il Duce knows enough history to realize

he could not emerge unscathed from a head-on confrontation with the Papacy. He

sees advantages to be gained in an alliance with the Church.

Mussolini wants to be able to say that

his is the first Italian government in modern history to be officially

recognized by the Pope.

Accordingly, II Duce seeks to create the

impression that he is a devout Catholic, though since boyhood he has not been a

churchgoer. Privately he scorns the rites and dogmas of the Church. An avowed

atheist in his youth, he had once written a pamphlet titled God Does Not Exist !

For its part, the Vatican is at first

sympathetic toward fascism. Though Pope Pius XI. (1922-1939) is critical of

fascism's use of violence, he considers Mussolini as preferable to all alternatives.

Secret negotiations now prepare the way for a dramatic reconciliation.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Italy's reconciliation with the Vatican

comes on February 11, 1929. Mussolini represents the king. Cardinal Gasparri

represents Pope Pius. In a solemn ceremony at noon in the Lateran Palace in

Rome, three historic documents are signed: The Lateran Treaty gives the Pope

full sovereignty and temporal power over the 110-acre Vatican City, now the

newest and smallest sovereign country in the world. Diplomatic relations between

the newly created state and the kingdom of Italy are established.

A separate financial agreement

compensates the Vatican for its surrender of claims to the old Papal States;

for a sum of about 19,000,000. The fact that the inhabitants of those States had

voted by an enormous majority for liberation from the Pope's rule mattered little.

A concordat defines the position of the

Church in the Fascist state. It establishes Catholicism as the official religion

of Italy. Many hail the reconciliation as one of the most significant events in the modern history of the Church.

Even Mussolini considers it one of the

greatest diplomatic triumphs of his career. He derives immense personal prestige worldwide.

But the agreements by no means end the friction between the Church and the Italian government. In 1931, Pius XI. will

express his strong disapproval of Fascist methods in his encyclical Non abbiamo bisogno.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Meanwhile, the situation is deteriorating

rapidly in the world economic arena.

With the collapse of the New York stock

market late in October 1929, the world enters a new period of economic and

political turmoil. Germany is hit particularly hard . This is just what Hitler

needs. The time for his final drive for power has arrived.

Increasingly hard times fuel the fires of

political pandemonium. Economic disasters trigger widespread social chaos. By

the end of 1931, more than six million Germans are unemployed; by 1933, more

than eight million.

Germany is heading toward national

bankruptcy. Tensions move toward the breaking point. The on-going disunity of

the political parties makes a drastic solution of the crisis inevitable. Germans

seek a strong deliverer.

A born political orator, Hitler uses the

economic crisis as a stepping-stone to more power. He gives Germans new hope.

He promises them stability, power, Lebensraum.

The confused multitude of German parties are unable to unite against him.

The National Socialist (Nazi) movement

gains supporters. In the 1932 elections, Nazis nearly double their popular vote,

winning 230 seats in the Reichstag (37 percent of the total number).

They are the largest party in parliament.

Hitler has proved himself unequaled in

his ability to exploit events to his own ends.

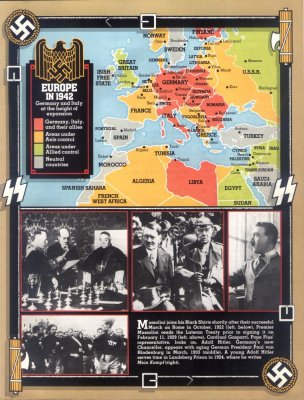

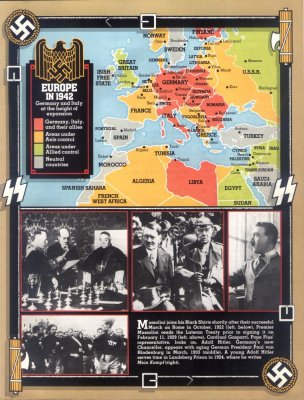

Europe in 1942 - Germany and Italy at the Height of Expansion

(click to enlarge)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

On January 30, 1933, Hitler is asked to

form a government. After years of careful planning, he has at last become

Chancellor.

The Weimar Republic is finished. A modern-day interregum —

a "time without an emperor" — it had lasted but 14 years.

The Third Reich has begun.

Hitler's emergence as Chancellor is

hailed enthusiastically by the Italian press. Mussolini naively views Hitler as

his Fascist protégé, someone he can control and utilize for his own purposes.

Hitler asks the Reichstag to pass an

enabling bill, giving his government full dictatorial powers for four years.

The parliament passes the sweeping legislation, and the Nazis assume complete

control of Germany. In 1934, the offices of Chancellor and President are merged.

Hitler assumes the title of Fuehrer und Reichskanzler.

In short order, the German dictator reinvigorates a demoralized country. He strengthens the

shattered economy, reduces unemployment and raises the standard of living.

But Hitler's aims far transcend his own

country's borders. He is convinced he has a great mission to perform. He feels

destined to become ruler of a great Germanic Empire. He holds an unshakable

conviction that the Reich will one day rule all of Europe — and from there seize

the leadership of the world! A new order will emerge in the world, with the German "master race" at its head!

Hitler compares himself with Charlemagne,

Frederick the Great and Napoleon. From his mountain fortress in Obersalzberg,

overlooking Berchtesgaden, the Fuehrer has a panoramic view of the Untersberg.

It is in this mountain, as legend has it, that Charlemagne still sleeps, and

will one day arise to restore the past glory of the German Empire.

"You see the Untersberg over there," Hitler tells visitors

in a mystical tone. "It is no accident that I have my residence opposite it."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Like Mussolini, Hitler — a Catholic by

birth — sees a need to come to terms with the Vatican.

On July 20, 1933, the Vatican signs a

concordat with the Nazi regime, protecting the rights of the Church under the

Third Reich. Pope Pius XI. hopes that Hitler will discourage the extreme

anti-Christian radicalism of National Socialism. For Hitler, the concordat gives

his new government an outward semblance of legitimacy.

But relations between Berlin and the

Vatican are strained. Pope Pius has no illusions about Naziism. He authors

several protests against Nazi practices. On March 14, 1937, Pius issues his

encyclical Mitbrennender Sorge

("With Burning Anxiety") against Naziism. It charges that the German state has

violated the 1933 concordat, and vigorously denounces the Nazi conception of life as utterly anti-Christian.

About the same time, Pius — an outspoken

adversary of communism — issues another encyclical,

Divine Redemptoris, denouncing the

Bolshevik campaign against religion. It pronounces the political philosophy

and the atheistic ideology behind Marxist doctrine as contrary to the Divine

Will and intrinsically evil.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In Italy, Mussolini has been vigorously

pursuing his vainglorious dream of a modern Roman Empire.

In 1896, Italy had suffered a humiliating

defeat in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) at the hands of King Menelik II. Italian forces

were crushed by an Ethiopian army at the Battle of Adowa. Ten thousand Italians

lay dead. The defeat was disastrous to Italian expansion in Africa.

The humiliation has not been forgotten.

The memory of Adowa still lives. The score must be settled.

Mussolini, the modern Caesar, casts eyes

toward Ethiopia. He sees its conquest as a means of restoring Roman grandeur.

On October 3, 1935, the Italian dictator

launches his first foreign military adventure. He invades the kingdom of

Ethiopia as the League of Nations weakly stands by.

After months of fighting, Adowa is avenged. Il Duce's African venture is a success

— a "Roman triumph." The armies of Emperor Haile Selassie are defeated.

On May 9, 1936, Italy formally annexes

Ethiopia. King Victor Emmanuel is proclaimed Emperor of Ethiopia. A month later,

a decree incorporates Ethiopia with the existing Italian colonies of Eritrea and

Italian Somaliland into a single great colony, Italian East Africa.

Mussolini now proclaims another

resurrection of the Roman Empire. "At last Italy has her empire," Il Duce

declares to an enormous crowd from the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia.

"Legionnaires!" he continues. "In this

supreme certitude raise high your insignia, your weapons, and your hearts to

salute, after fifteen centuries, the reappearance of the empire on the fated hills of Rome."

Though a great success at home, Mussolini's Ethiopian adventure isolates Italy from the Western democracies. As

a result, Mussolini turns to Hitler as an ally. In October 1936, the

"Berlin-Rome Axis" is formed. Hitler and Il Duce forge an agreement to

coordinate their foreign policies. As in the days of Otto the Great, Germany ties its destiny to Italy !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

While the fight is going on in Ethiopia,

events are happening in quick succession in Germany.

In a daring move, Hitler orders German

troops to march into the demilitarized zone of the Rhineland, established by the

Treaty of Versailles. It is March 7, 1936. The French fail to call Hitler's bluff.

A year earlier, Hitler had unilaterally

abrogated the disarmament clauses of the Versailles treaty and had begun to

rearm openly.

In March 1938, Germany occupies Austria,

which is quickly incorporated into the Greater German Reich. In September,

Hitler demands and receives the cession of the Sudetenland area of

Czechoslovakia ("my last territorial claim in Europe," he says).

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain of

Britain yields to Hitler's demands, hoping against hope that concessions to the

dictator will promote "peace in our time."

On May 22, 1939, ties between Hitler and

Mussolini become even closer as the two form a 10-year political and military

alliance — the Pact of Steel. The Italian press proclaims,

"The two strongest powers of Europe have now bound themselves to each other for peace and war."

In August 1939, Germany and Soviet Russia

sign a nonaggression pact, guaranteeing Soviet nonintervention in Hitler's ventures in the

West. Hitler's eastern flank is now secure. The stage is set. A catastrophe is about to engulf the world !

In a final last-minute appeal to head off

the outbreak of world conflict, the new Pope, Pius XII., declares on August 24,

"Everything can be lost by war; nothing is lost by peace."

But Hitler's plan is set. Casting aside all pretenses of

peaceful aspirations, the German dictator accuses and attacks Poland on September 1.

The peace of Europe is broken. World War II has begun — a struggle for the mastery of the world !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Pope Pius XI. died in March 1939. His

successor as war breaks out in Europe is Eugenio Pacelli, now Pius XII. Few

Popes will be the subject of as much controversy as he.

In 1917, Pacelli had been sent as Papal

nuncio (ambassador) to Munich to negotiate a concordat with the Bavarian Court.

This accomplished, he was sent to Berlin in 1925 with the same aim. After

concluding the concordat with the Weimar Republic, Pacelli was recalled to Rome

in 1929 and created a cardinal and Vatican secretary of state.

As Cardinal Pacelli, he drew up and signed the concordat with

Hitler's Nazi Germany on behalf of Pius XI. in the summer of 1933.

Pacelli's years in Germany gave him a

fluency in the German language and a great love for the German people. In view

of this, his proclaimed neutrality as wartime Pontiff will be questioned. After

the war he will be accused of failing to denounce Hitler and neglecting to speak

out publicly against Hitler's "final solution" to the "Jewish problem." Some

critics will declare that by remaining silent he became an accomplice to genocide.

Pledged to neutrality, Pius believes the

Holy See can play a peacemaking role if it maintains formal relations with all

the belligerents. Yet he is keenly concerned about the Jews.

Pius faces a terrible choice . He knows

the capabilities of Naziism, having been closely associated with the anti-Nazi

encyclical Mit brennender Sorge.

In September 1943, Germans occupy Rome.

The dilemma of Pius XII. becomes even more acute. Nazi troops are now camped on

his very doorstep. Public condemnation of Hitler could lead to reprisals, even

invite a Nazi invasion of the Vatican. That would jeopardize the Holy See's

diplomatjc efforts on behalf of the Jews and end any influence the Papacy might have in favor of peace.

Pius issues repeated private protests

against Nazi atrocities and is even involved in efforts to shelter Jews and

political refugees. But he stops short of outright public denunciation. Faced

with circumstances in which his public statements might further rouse Hitler

against the Jews and expose German Catholics to charges of treason, he takes the side of caution.

In retrospect, sympathetic observers will

assert that, under the circumstances, Pius did all he could against a powerful

totalitarian government. Public denunciation would not have stopped the Nazi leadership anyway.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

At the outset of war, Germany seems

invincible. Hitler subjects a whole continent, directly or indirectly, to his

power. Not since the days when the Roman Empire was at its height has one man

ruled such vast expanses in Europe.

But Hitler's is an ephemeral empire. In

1941, the German dictator makes Napoleon's disastrous mistake of invading

Russia. Operation Barbarossa is a fatal blunder. The tide of war begins to turn.

In the end, the Fuehrer and the Duce die

within days of each other, their dreams of conquest and empire shattered.

Mussolini is executed by Italian

partisans on April 28, 1945. His megalomaniac attempt to restore the Roman

Empire ends in ruin. Hitler, it is declared, has now committed suicide in his

Berlin bunker on April 30, as his "Thousand-year Reich" crashes around him.

The war in Europe is over.

Italy is devastated. Germany lies in

ruins. Some observers declare Germany will never rise again.

Others say it will take at least 50, maybe even 100 years or

more. Privately, some Germans are thinking that no defeat is final.

As the victors and vanquished alike pick

up the pieces of their shattered and now-divided continent, a centuries-old

concept again takes its rise in the minds of Europeans — the ideal of a United

States of Europe. Europe slowly sets out on the path toward its final — and most

crucial — revival.

CHAPTER - X

THE FINAL UNION(Keep in mind that this chapter was first written in 1984)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

It is the spring of 1945. The fighting in Europe is over.

Never has war been more destructive. The human and material losses are

incalculable. The staggering enormity of the tragedy gradually becomes clear.

The appalling cost in human lives totals more than 40 million civilian and

military deaths.

Europe lies in ruins. Germany in particular has been hard hit. Many

wonder whether war-torn Germany will ever rise again. Europe has hit bottom. It

has been the pattern of European history: catastrophe, followed by revival, followed by catastrophe.

The war-ravaged Continent slowly begins to pick up the pieces. The

suffering and destruction of World War II prompt many to ask how such a

catastrophe might be avoided in the future. Many wonder: Is Europe doomed to oscillate between

order and chaos, between power and ignominy? Or might a new path toward peace and stability be found ?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

In a celebrated speech at Zurich, Switzerland, in September 1946,

Winston Churchill suggests a possible solution:

"We must build a kind of United States of Europe."

Once again, an age-old ideal resurfaces.

The devastation of two world wars has made the limitations of national

sovereignty painfully evident. If Europe's individual nationalisms could be

submerged within the context of European supra nationalism, many feel that

future continental conflagrations could be averted. If Europe could become one

family of nations, historic enmities could be put to rest.

The plan has highly significant overtones. For centuries, statesmen

have advocated the union of European nations. Now, a fresh movement toward unity

arises from the devastation of World War II.

But how to begin ?

It is Churchill, among others, who again suggests a course:

"The first

step in the re-creation of the European family must be a partnership between France and Germany."

The reconciliation of these two age-old enemies is widely viewed as the

essential cornerstone of peace in postwar Europe. In essence — the re-creation of

the Empire of Charlemagne !

How, specifically, might this be achieved ?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

A scheme is devised to unite France and Germany within a common venture

designed to bind their economic destinies so tightly together that another

intra-European war could not occur. The result is the European Coal and Steel

Community (ECSC), created by the Treaty of Paris in April 1951.

The ECSC is a first step toward European integration. It creates a

common transnational authority to pool French and German iron, coal and steel

resources. The project is extended to include Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands

and Luxembourg.

The wheels of European industry have begun to turn again. Massive U.S.

aid in the form of the Marshall Plan has helped spur European recovery. And the

ECSC has shown Europeans the advantages of cooperation.

Now, a further step is taken on the road toward integration.

Individually, the nations of Western Europe — fragmented by internal barriers — are

merely secondary influences in world affairs. But united, many come to realize,

their joint economic strength could allow them to recover some of their lost

influence and give them a major voice in the global arena.

The signing of the Treaty of Rome on March 25, 1957, creates the

European Economic Community (EEC), or Common Market. Its six charter members are

the same countries associated in the ECSC. (By 1986, the number of members will

have grown to 12.)

European Unity - Spiritual and Political

(click to enlarge)

The EEC's initial goal is to remove trade and economic barriers between

its members and unify their economic policies. But the ultimate hope is that the

organization will be able to bring about the eventual political unification of

Europe. Many hail the EEC as the nucleus of a future "United States of Europe."

In short order the EEC becomes the world's most powerful trading bloc.

And West Germany — at the center of the European continent — becomes the most

powerful nation of Europe west of the Soviet Union.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Again, Europe has set out on the road to unity. Past articles in this

series have shown that the Roman dream of a united Europe has permeated the

history of the Continent.

Justinian dreamed of restoring the Roman Empire. He accomplished it in

A.D. 554, healing the "deadly wound" administered to Rome by barbarian

invaders in 476. But his restoration was short-lived.

In A.D. 800, Charlemagne was crowned as imperator Romanorum,

again restoring the Roman Empire in the West.

In Charlemagne, Western Europe had a Christian Caesar, a Roman emperor born of

Germanic race. His realm was the spiritual heir of the old Western Roman Empire.

Charlemagne was rex pater Europae — "King

Father of Europe." He showed Europeans the ideal of a unified Christian Empire.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the memory of the once-great Roman Empire lived as a

vital tradition in the hearts of Europeans.

In 962, Otto the Great revived Charlemagne's Empire as the first fully

German Reich. The Sacrum Romanum Imperium

Nationis Germanicae — Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation — made its

debut. Otto's octagonal crown became the very symbol of the concept of European

unity. Germany became the power center of the Empire.

In the 16th century, the great Habsburg Emperor Charles V. pursued

tirelessly, though unsuccessfully, the medieval ideal of a unified Empire

embracing the entire Christian world. Napoleon, too, dreamed of a resurrected

Roman-European civilization, dominated by France. He considered himself the heir

and successor to Caesar and Charlemagne.

Mussolini likewise envisioned a modern Roman Empire. In 1936 he

proclaimed another resurrection of the Roman Empire, claiming succession to

imperial Rome.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Along with the time-honored system of Roman-inspired government,

another pattern has stood out in the panorama of European history: the intimate

relationship of the spiritual with the secular power.

Throughout the Middle Ages, leaders considered the Church at Rome to be

God's chosen instrument in spiritual matters. The Holy Roman Empire was

regarded as God's chosen political organization over Western Christendom. Pope

and Emperor were regarded as God's vice-regents on earth. This intimate alliance

of Church and State served the needs of both institutions. The Empire exercised

its political and military powers to defend religion and enforce internal

submission through religious uniformity. The Church, in turn, acted as a glue

for Europe, holding together the differing nationalities by the tie of common

religion.

This ideal in Church-State relations was never completely realized, as

we have seen in the frequent conflicts between Emperors and Popes for the

leadership of Christian Europe. Yet despite their rivalry, the Papacy and Empire

remained closely associated, their need for each other overriding disagreements

of lesser importance.

Justinian became inheritor of the Roman Empire as Christianized by

Constantine. He acknowledged the supremacy of the Pope in the West. Charlemagne

received the imperial crown at the hands of Pope Leo III., initiating a close

alliance between Pope and Empire. Otto the Great was crowned Holy Roman Emperor

by Pope John XII., reviving Charlemagne's Empire in an alliance between Emperor

and Church. Pope Clement VII. crowned Charles V. as Holy Roman Emperor. Charles

fought hard to maintain the spiritual unity of Europe.

Napoleon's coronation was consecrated by Pope Pius VII. Mussolini, too,

recognized the need to come to terms with the Vatican, as did Adolf Hitler a

few years later. All these successors of the Roman Caesars understood the vast

importance of the Papacy in European affairs. But what of the present and

future role of the Vatican in Europe in these latter days of the 20th century and beyond ?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Over the past few decades the authority and unity of the Roman Catholic

Church have been severely shaken. The festering issues of birth control,

abortion, divorce, celibacy, homosexuality, women in the priesthood, political

activism of priests, child sexual abuse and distribution of ecclesiastical power have greatly

troubled the Church. Many even in the upper echelons of the Vatican hierarchy

have expressed apprehension over the Church's future.

At the same time, the continent of Europe itself stands at an historic

crossroads. Divided ideologically between East and West and beset with serious

economic and military concerns, Europe faces crucial decisions on its future.

Like the Catholic Church, Europe has been weakened by division. And both

prelates and politicians alike realize that a house divided against itself cannot stand.

In the face of this division, voices within both European political

circles and the Catholic Church are appealing for UNITY. But how, many ask, is that elusive unity

to be achieved? How are the rifts to be healed — both within the Church and within Europe itself ?

The record of the recent past does not augur well for the future. On a

purely political basis, the nations of Europe have been unable to unite. Strides

have been made, but the slow process of gradually increasing the powers of the

EEC's political institutions has not worked as hoped. The process has resulted

in only minimal surrender of national political sovereignty. The institutions

are invested with no substantial powers. And Eastern Europe is still cut off.

(Notice, when this was originally written it was true,

but today, radical changes have erased those last 2 obstacles mentioned)

Likewise, the Catholic Church within remains philosophically divided

between liberal and conservative, despite the best efforts of unity-minded

churchmen. Confronted with these realities, leading European politicians and

Catholic clergymen have come to an important realization. There is only one

possible course for the future, they believe.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

If they are to solve their respective problems, Europe and the Catholic

Church need each other's help. Their common need for unity can be achieved

only by working together. Once again, the past points the way to the future.

Influential churchmen inside the Vatican have come to believe that the

only way to inspire unity and bring new life to the Church is to

plunge it into a cause larger than itself. That cause, many believe, is the unification of Europe !

In turn, many of Europe's political leaders see a role for the Church in

their efforts. They believe the Church might once again exercise its powerful

cohesive effect on Europe, providing the glue — the tie of common religion — to hold

Europe together politically.

Again, as in centuries past, Europeans are beginning to appreciate that

religion and politics are interdependent. In essence, they are envisioning a

reconstitution of the whole of classic Europe, along the lines of the old Holy

Roman Empire, under Catholic aegis. The dream of the Holy Roman Empire yet lives !

The time-honored theme of European unity on the basis of a common

religious heritage has been raised frequently by Pope John Paul II. For him it

is no casual, passing concern. He has made it very clear that he believes he has

a literal calling from God to unite Europe !

During his well-publicized trip to his native Poland in June 1979, the Pope declared:

"Europe, despite its present and long-lasting division of regimes, ideologies and economic systems,

cannot cease to seek its fundamental unity and must turn to Christianity. . . .

Economic and political reasons cannot do it. We must go deeper...."

In Santiago, Spain, in 1982 he proclaimed the following, in what he

called a "Declaration to Europe":

"I, Bishop of Rome and Shepherd of the Universal Church, from Santiago, utter to you, Europe of the ages, a cry full of

love: Find yourself again. Be yourself. Discover your origins, revive your roots."

The Pope has repeatedly stressed that Europe must seek religious unity

if it is to advance beyond its present divisions. At his final mass during his

trip to Poland in June 1983, John Paul prayed for

"all the Christians of East

and West, that they become united in Christ and expand the Kingdom of Christ throughout the world."

The following September, 1982, in the first Papal pilgrimage to Vienna,

Austria, in two centuries, the Pope again urged Europeans on both sides of the

Iron Curtain to unite on the basis of their common Christian heritage. To a

crowd of 100,000, he emphasized Europe's unity in

"the deep Christian roots and the human and cultural values which are sacred to all Europe."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The theme of European unity on the basis of common religious heritage

is not unique to John Paul II. Since World War II, each Pope has thrown his

weight behind moves for the creation of a supranational European community.

Pope John XXIII. said that Catholics should be "in the front ranks" of

the unification effort. Pope Paul VI. was especially vocal in his support for

European unity. In November 1963, he declared:

"Everyone knows the tragic history of our century. If there is a means of preventing this from happening

again, it is the construction of a peaceful, organic, united Europe.

In 1965, Paul VI. observed that

"a long, arduous path lies ahead. However, the Holy See hopes to see the day born

when a new Europe will arise, rich with the fullness of its traditions."

Perhaps the most forceful of Paul VI.'s calls for European unification

came on October 18, 1975. It was an address in Rome to participants in the Third

Symposium of the Bishops of Europe. Present were more than 100 bishops,

cardinals and prelates representing 24 European countries. The Pope declared:

"Can it not be said that it is faith, the Christian faith,

the Catholic faith that made Europe ...?

Paul VI continued:

"And it is there that our mission as bishops in Europe takes on a gripping perspective.

No other human force in Europe can render the service that is confided to us, promoters of the faith,

to reawaken Europe's Christian soul, where its unity is rooted."

Paul VI. called the Catholic faith "the secret of Europe's identity." In

discovering this secret, he said, Europe could then go on to perform

"the providential service to which God is still calling it."

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The Popes' calls for the spiritual unity of Europe have been echoed by

influential spokesmen in the political arena.

Prominent among these is Dr. Otto von Habsburg, a key figure in the

movement for European unification. Dr. Habsburg is the eldest son of the last

Austro-Hungarian Emperor and a member of the European Parliament. Inter-European

unity has long been a quest of the Habsburgs, as we have seen. Dr. Habsburg often speaks of

the similarities between the Holy Roman Empire of the Middle Ages and his view

of a coming "United States of Europe."

Dr. Habsburg has long advocated a strong religious role in

any future united Europe. He regards the Roman Catholic Church as Europe's ultimate bulwark.

"The cross doesn't need Europe," he once stated,

"but Europe needs the cross."

Europeans, he believes, must be reawakened to their historical religious heritage.

"If we take Christianity out of the European development,

there is nothing left," he declares. "The soul is gone."

Dr. Habsburg has also

called attention to the potential role of the crown of the Holy Roman Empire,

which today resides in the Schatzkammer (Royal Treasury) in Vienna.

Christopher Hollis, in the foreword to Dr. Habsburg's book The Social Order of Tomorrow,

points out that Dr. Habsburg

"would like to see Europe resume her essential

unity, and in the symbolism of that unity he thinks that the imperial crown of

Charlemagne and of the Holy Roman Empire might well have its part to play."

It is to the model of the Holy Roman Empire that many European political figures

and leading churchmen are now looking for the answer to today's political and

religious woes. A revived alliance between church and "empire," they believe, may be the

very key — the only key — to European survival in the face of perilous world conditions !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Forces already have been set in motion that will revolutionize the face

of Europe and the role of the Roman Catholic Church. As often explained in the

pages of The Plain Truth, Bible prophecy reveals that

current efforts toward Church unity and European political integration will be achieved !

The result will be the emergence of a religious-political union in Europe, in the spirit of the old

Holy Roman Empire — a final revival, in this age of the Bomb, of the ancient Roman political system !

As we have seen in this series of articles, numerous revivals of the

Roman Empire have arisen in Europe in the centuries since the fall of ancient

Rome. In Revelation 17, these revivals are represented by the seven heads of a

wild animal. Six have already occurred, from Justinian to Mussolini. One last

restoration of this great political system is yet to arise.

This confederated Europe will be an immense political, military and

economic power — a great Third Force in world affairs, a superpower in its own

right. Prophecy further reveals that this powerful church-state union will be

composed of "ten horns" — meaning 10 nations or groups of nations (Rev.

l7:3) — under the overall leadership of a single political figure (verse 13).

Europe will again have a single political head of state! Moreover, prophecy

foretells that a religious figure of unprecedented power and authority will sit

astride the "empire," directing it as a rider guides a horse (Rev. 17:3).

To counter the ongoing spread of atheism, secularism and consumerism,

the Vatican — as in centuries past — will be forced to become a major power in the

international arena. The political muscle of the Papacy will be reinvigorated.

The "spiritual unity" of the Continent — as so often urged by recent Popes — will be realized !

(Notice, since this was originally written in the 1980's the Berlin wall came down

and the European-Union now includes 27 countries and has its own constitution — and many efforts are

being made to officially recognize the pope's religion as the state religion of the European Union)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Now notice further: In the second chapter of the Old Testament book of

Daniel, he interprets the kings dream where the Roman Empire and its predecessors are pictured as a giant human

figure representing five kingdoms. The figure's 10 toes correspond to the fifth kingdom and to the 10 end-time

national units also described (as "horns") in Revelation 17. The prophecy of Daniel reveals that

these 10 entities will constitute a political system that will exist at the

return of Jesus Christ to establish the kingdom of God on this earth (Dan. 2:44, 45).

(Notice, only five world kingdoms, the last of which is taking shape now in Europe)

The original Roman Empire was broken into two "legs," as pictured in

the human image of the kings dream and Daniel's prophecy — the Eastern Empire centered at Byzantium

(Constantinople) and the Empire of the West centered at Rome. Thus it is very

possible that the coming reconstituted Roman Empire will be composed of two

distinct yet cooperative parts: one comprising nations of Western Europe, the

other incorporating nations freed from Soviet dominance in Eastern Europe.

Given the fact of five toes on each foot of the human image, possibly five

entities will come from the West and five from the East.

With this in mind, Pope John Paul II.'s appeals to Christians behind the

Iron Curtain take on added significance. His voice is a source of enormous

influence in that region. Many East Europeans have caught his vision of a

pan-European Christian alliance against the secular materialism of our modern age.

"The Pope," observes one news commentator, "has undertaken the liberation

of Eastern Europe." Vatican observers speculate that the voice of the Papacy

might continue to stir religious and nationalistic fervor in Eastern Europe,

which, together with other factors, could weaken the Kremlin's hold sufficiently

to open the way for a political deal between Europe and the Kremlin — a deal that

would allow elements of Eastern Europe to associate themselves with an evolving

West European union. (Notice, since this was originally written the Pope has indeed succeeded)

In this age of intercontinental missiles, the nations of Eastern Europe

no longer adequately fulfill their original function as a security buffer for

the Soviet Union. And they are a severe drain on Soviet economic and military

resources. Many political observers are therefore suggesting that the Kremlin

might soon be willing to strike a deal: the withdrawal of its military forces

from Eastern Europe in exchange for the neutralization of Eastern Europe and the

withdrawal of American forces from Western Europe !

The resulting political vacuum in Europe could then be filled by a new

entity, the prophesied resurrected Holy Roman Empire !

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

What is transpiring on both sides of the Iron Curtain today are the

first steps in the refashioning of Europe into a new, yet old, alignment. As

George Bailey, in his perceptive book Germans, suggests:

"Can we be sure that history has written finis to what was perhaps the

grandest design ever conceived by man: the Holy Roman Empire?"

Declares Otto von Habsburg:

"We are well beyond the point of no return where you can still go back into the [recentj past. Of course,

we have not yet arrived at the other shore; but we can't go back."

A united Europe is inevitable.

Unity is not a condition which nations achieve by some natural and

inevitable tendency. Unity is created or imposed by vigorous human action, by

effort and will. Europe awaits a modern Charlemagne, another Otto the Great, a

second Charles V. — a champion to resurrect the tradition of imperial unity.

The coming Renovatio imperii Romanorum — restoration

of the Empire of the Romans — will astound the world !

Europe — and the Church of Rome — will again be powers to reckon with.

Notice, since this was originally written there is no more Iron Curtain (Berlin wall)

A young mid-twenties, German born and raised, musician by the name of Gernot had come to my city to study music at the university for a few months in the early eighties.

We became neighbors and friends, we talked about the eventual destruction of the dreaded wall that separated

his country and of the coming monetary unit that was to become the Euro. Both of these had yet to materialize

and my German friend had emphatically refused to believe that the Iron Curtain would fall within his lifetime.

He was born there and yet could not see the day when his own country could ever be reunited.

About 2 years after returning to his homeland he was there to witness what he thought he would never see.

In the public interest.

Text by: Keith W. Stump