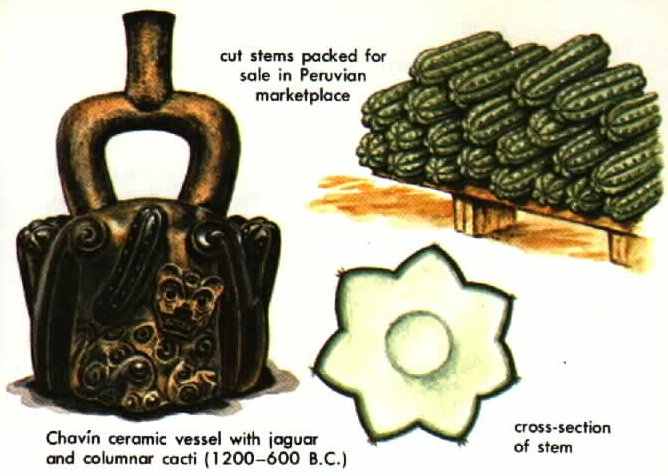

(San Pedro continued)

Although cimora is often made from San Pedro alone, several field researchers indicate that a variety of other plants may sometimes be added to the brew. These include the cactus Neoraimondia macrostibas, an Andean species the chemistry of which has not yet been determined; the shrub Pedilanthus tithymaloides of the castor oil family; and the campanulaceous Isotoma longiflora. All these plants may have biodynamic constituents. On occasion, other more obviously potent plants are added - Datura, for example.

Only recently have researchers become aware of the importance of the "secondary" plant ingredients often employed by primitive societies. The fact that mescaline occurs in the San Pedro cactus does not mean that the drink prepared from it may not be altered by the addition of other plants, although the significance of the additives in changing the hallucinogenic effects of the brew is still not fully understood.

Cimora is the basis of a folk healing ceremony that combines ancient indigenous ritual with imported Christian elements. An observer has described the plant as "the catalyst that activates all the complex forces at work in a folk healing session, especially the visionary and divinitory powers" of the native medicine man. But the powers of San Pedro are supposed to extend beyond medicine; it is said to guard houses like a dog, having the ability to whistle in such unearthly fashion that intruders flee in terror.

Although San Pedro is not closely related botanically to peyote, the same alkaloid, mescaline, is responsible for the visual hallucinations caused by both. Mescaline has been isolated not only from San Pedro but from another species of Trichocereus. Chemical studies of Trichocereus are very recent, and therefore it is possible that additional alkaloids may yet be found in T. pachanoi.

Trichocereus comprises about 40 species of columnar cacti thot grow in subtropical and temperate parts of the Andes.

There is no reason to suppose that the use of the San Pedro cactus in hallucinogenic and divinatory rituals does not have a long history. We must recognize, certainly that the modern use has been affected greatly by Christian influences. These influences are evident even in the naming of the cactus after Saint Peter, possibly stemming from the Christian belief that Saint Peter holds the keys to heaven. But the overall context of the ritual and our modern understanding of the San Pedro cult, which is connected intimately with moon mythology, leads us to believe that it represents an authentic amalgam of pagan and Christian elements. Its use seems to be spreading in Peru.

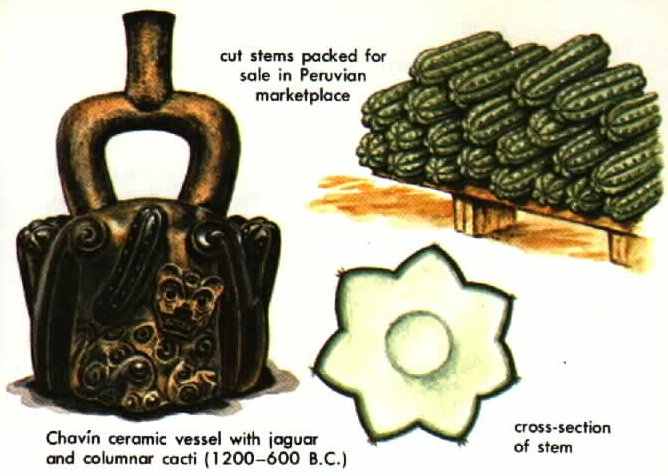

Cawe or Pachycereus pecten-aboriginum, is one of the plants combined with the San Pedro cactus by the Tarahumare of Mexico. It is not definitely known whether this tall organ cactus is hallucinogenic.

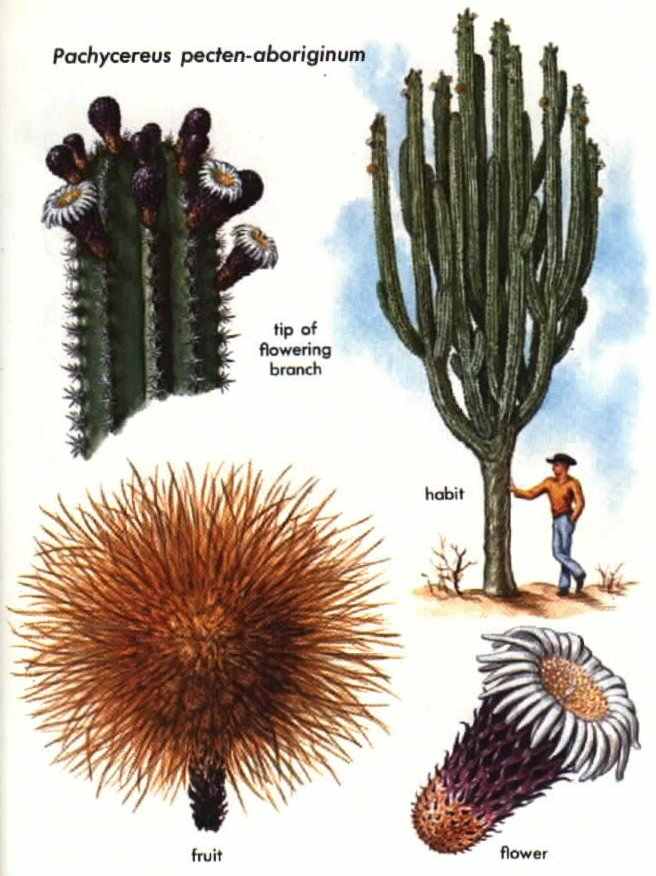

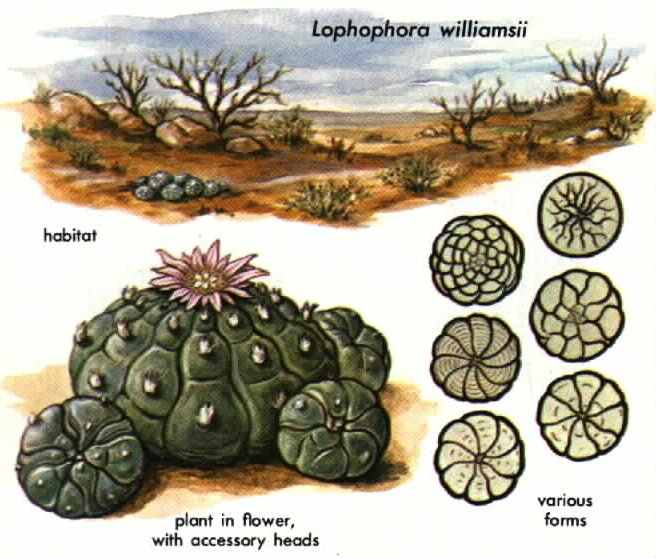

PEYOTE (lophophora williamsii), an unobtrusive cactus that grows in rocky deserts, is the most spectacular hallucinogenic plant of the New World. It is also one of the earliest known. The Aztecs used it, calling it peyotl.

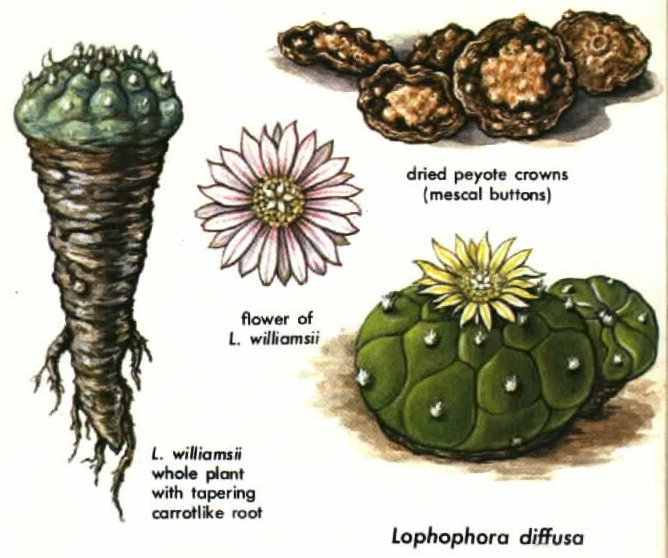

Peyote is a small, fleshy, spineless cactus with a rounded gray-green top, tufts of white hair, and a long carrotlike root. It rarely exceeds 7-1/2 inches in length or 3 inches across. The Indians cut off the crowns to sun-dry into brown, discoidal "mescal buttons" that last long periods and can be shipped to distant points for use. When the top is severed, the plant often sprouts new crowns so that many-headed peyotes are common.

Peyote was first described botanically in 1845 and called Echinocactus williamsii. It has been given many other technical names. The one used most commonly by chemists has been Anhalonium lewinii. Most botanists now agree peyote belongs in a distinct genus, Lophophora. There are two species: the widespread L. williamsii and the local L. diffusa in Querétaro.

Peyote is native to the Rio Grande valley of Texas and northern and central parts of the Mexican plateau. It belongs to the cactus family, Cactaceae, comprising some 2,000 species in 50 to 150 genera, native primarily to the drier parts of tropical America. Many species are valued as horticultural curiosities, and some have interesting folk uses among the Indians.

USE OF PEYOTE BY THE AZTECS was described by Spanish chroniclers. One reported that those who ate it saw frightful visions and remained drunk for two or three days; that it was a common food of the Chichimeca Indians, "sustaining them and giving them courage to fight and not feel fear nor hunger nor thirst; and they say that it protects them from all danger." In 1591, another chronicler wrote that the natives who eat it "lose their senses, see visions of terrifying sights like the devil, and are able to prophesy their future with 'satanic trickery.' "

Dr. Hernández, the physician to the King of Spain, described the cactus as Peyotl zacatecensis and wrote of its "wonderful properties." He took note of its small size and described it by saying that "it scarcely issues from the earth, as if it did not wish to harm those who find and eat it." Recent archaeological finds of peyote buttons in the state of Texas are approximately 1 ,000 years old.OPPOSITION TO THE USE OF PEYOTE by the Aztecs was strong among the Spanish conquerors. One early Spanish church document likened the eating of peyote to cannibalism. Upset by the religious hold that peyote had on the Indians, the Spanish tried, with great vigor but little success, to stamp out its use.

By 1720, the eating of peyote was prohibited throughout Mexico. But despite four centuries of civil and ecclesiastical persecution, the use and importance of peyote have spread beyond its early limited confines. Today it is so strongly anchored in native lore that even Christianized Indians believe that a patron saint—El Santo Niño de Peyotl—walks on the hills where peyote grows.

There is continuing opposition in certain religious organizations in the United States to the Indians' use of peyote as a ceremonial sacrament. Nevertheless, the federal government has never seriously questioned or interfered with the practice since it is essentially a religious one. Those tribes living far from sources of peyote—some as far north as Canada—can legally import mescal buttons by mail. Despite constitutional guarantees separating church and state, however, a few states have enforced repressive laws against even the religious use of peyote.

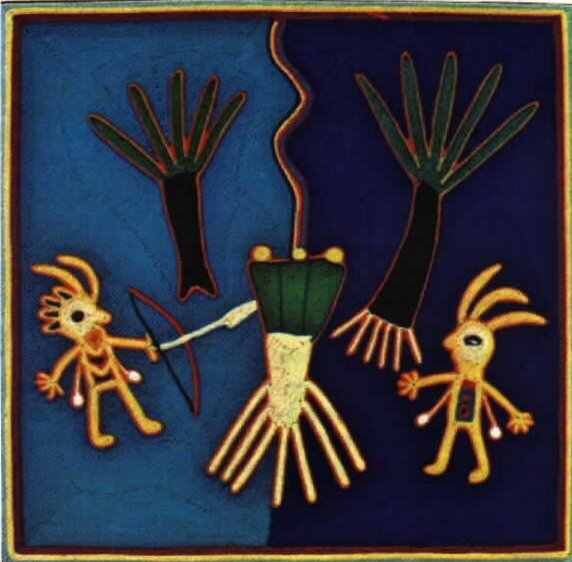

RELIGIOUS IMPORTANCE OF PEYOTE persists among the Tarohumare, Huichol, and other Mexican Indians. The Tarahumare believe that when Father Sun left earth to dwell above, he left peyote, or hikuli, to cure man's ills and woes; thot peyote sings and talks as it grows; that when gathered it sings happily in its bags all the way home; and that God speaks through the plant in this way.

Many legends about the supernatural powers of peyote underlie its religious importance. It might be esteemed merely as an everyday medicine, but it hos been exalted to a position of near-divinity. The peyote-collecting trip of the Huichols, for example, is highly religious, requiring pilgrims to forego adult experiences, especially sexual, for it reenacts the first peyote quest of the divine ancestors. The pilgrims must confess in order to become spirit and enter into the sacred country through the gateway of clashing clouds, a journey which, according to their tradition, repeats the "journey of the soul of the dead to the underworld."

EFFECTS OF PEYOTE on the mind and body are so utterly unworldly and fantastic that it is easy to understand the native belief that the cactus must be the residence of spirit forces or a divinity. The most spectacular of the many effects is the kaleidoscopic play of indescribably rich, colored visions. Hallucinations of hearing, feeling, and taste often occur as well.

The intoxication may be divided into two periods: one of contentment and extrasensitivity, followed by artificial calm and muscular sluggishness at which time the subject begins to pay less attention to his surroundings and increase his introspective "meditation.' Before visions appear, some three hours after eating peyote, there are flashes and scintillations in colors, their depth and saturation defying description. The visions often follow a sequence from geometric figures to unfamiliar and grotesque objects that vary with the individual.

Though the colored visual hallucinations undoubtedly underlie the rapid spread of the use of peyote, especially in those Indian cultures where the quest for visions has always been important, many natives assert that visions are "not good" and lack religious significance. Peyote's reputation as a panacea and all-powerful "medicine" - both in physical and psychic sense - may be equally responsible for its spread.

USE OF PEYOTE IN THE UNITED STATES first came to public attention about 1880 when the Kiowa and the Comanche Indians established a peyote ceremony derived from the Mexican but remodeled into a visionquest ritual typical of the Plains Indians. Use of peyote had been recorded earlier, in 1720, in Texas. How the use of peyote diffused from Mexico north, far beyond the natural range of the cactus, is not fully known. During the 1880's, many Indian missionaries were active in spreading the peyote ceremony from tribe to tribe. By 1920, the peyote cult numbered over 13,000 faithful in more than 30 tribes in North America. It was legally organized, partly for protection against fierce Christian - missionary persecution, into the Native American Church, which now claims 250,000 members. This cult, a combination of Christian and native elements, teaches brotherly love, high moral principles, and abstention from alcohol. It considers peyote a sacrament through which God manifests Himself to man.