.

Contents...1-10...11-20...21-30...31-40...41-50...51-60...61-70...71-80...81-90

91-100...101-110...111-120...121-130...131-140...141-150...151-156...Index

.

Detail from fresco at Sacuala, Teotihuacán, Mexico, showing four greenish ''mushrooms" that seem to be emerging from the mouth of a god, possibly the Sun God.

EARLY USE OF THE SACRED MUSHROOMS is known mainly from the extensive descriptions written by the Spanish clerics. For this we owe them a great debt.

One chronicler, writing in the mid-1500's, after the conquest of Mexico, referred frequently to those mushrooms " which are harmful and intoxicate like wine, " so that those who eat them "see visions, feel a faintness of heart and are provoked to lust''; the natives "when they begin to get excited by them start dancing, singing, weeping. Some do not want to eat but sit down . . . and see themselves dying in a vision; others see themselves being eaten by a wild beast; others imagine that they are capturing prisoners of war, that they are rich, that they possess many slaves, that they had committed adultery and were to have their heads crushed for the offense...."

A work of Aztec medicine mentions three kinds of intoxicating mushrooms. One, teyhuintli causes " madness that on occasion is lasting, of which the symptom is an uncontrollable laughter; there are others which . . . bring before the eyes all sorts of things, such as wars and the likeness of demons. Yet others are not less desired by princes for their festivals and banquets, and these fetch a high price. With night-long vigils are they sought, awesome and terrifying."

SPANISH OPPOSITION to the Aztecs' worship of pagan deities with the sacramental aid of mushrooms was strong. Although the Spanish conquerors of Mexico hated and attacked the religious use of all hallucinogens - peyote, ololiuqui, toloache, and others - teonanocatl was the target of special wrath. Their religious fanaticism was drawn especially toward this despised and feared form of plant life that, through its vision-giving powers, held the Indian in awe, allowing him to commune directly with his gods. The new religion, Christianity, had nothing so attractive to offer him. Trying to stamp out the use of the mushrooms, the Spaniards succeeded only in driving the custom into the hinterlands, where it persists today. Not only did it persist, but the ritual adopted many Christian aspects, and the modern ritual is a pagan-Christian blend.

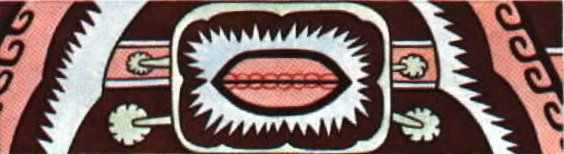

The pagan god of the underworld speaks through the mushroom, teononocatl, as represented by a Mexican artist in the 16th century. (From the Magliabecchiano Codex, Biblioteca Nazionole, Florence.)

IDENTIFICATION OF THE SACRED MUSHROOMS was slow in coming. Driven into hiding by the Spaniards, the mushroom cult was not encountered in Mexico for four centuries. During that time, although the Mexican flora was known to include various toxic mushrooms, it was believed that the Aztecs had tried to protect their real sacred plant: they had led the Spaniards to believe that teonanacatl meant mushroom, when it actually meant peyote. It wos pointed out that the symptoms of mushroom intoxication coincided remarkably with those described for peyote intoxication and that dried mushrooms might easily have been confused with the shriveled brown heads of the peyote cactus. But the numerous detailed references by careful writers, including medical men trained in botany, argued against this theory.

Not until the 1930's were botanists able to identify specimens of mushrooms found in actual use in divinatory rites in Mexico. Later work has shown that more than 20 species of mushrooms are similarly employed among seven or eight tribes in southern Mexico.

THE MODERN MUSHROOM CEREMONY of the Mazatec Indians of northeastern Oaxaca illustrates the importance of the ritual in present-day Mexico and how the sacred character of these plants has persisted from pre-conquest times. The divine mushrooms are gathered during the new moon on the hillsides before dawn by a virgin; they are often consecrated on the altar of the local Catholic church. Their strange growth pattern helps make mushrooms mysterious and awesome to the Mazatec, who call them 'nti-si-tho, meaning "worshipful object that springs forth." They believe that the mushroom springs up miraculously and that it may be sent from outer realms on thunderbolts. As one Indian put it poetically: "The little mushroom comes of itself, no one knows whence, like the wind that comes we know not when or why."

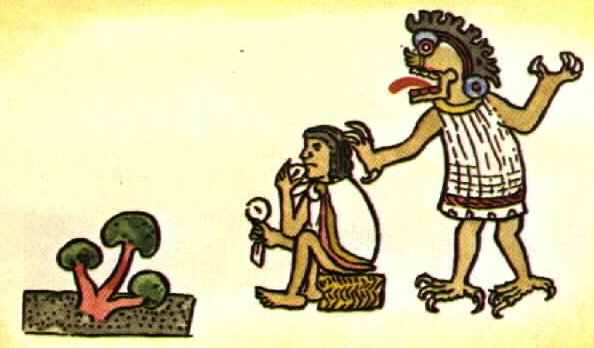

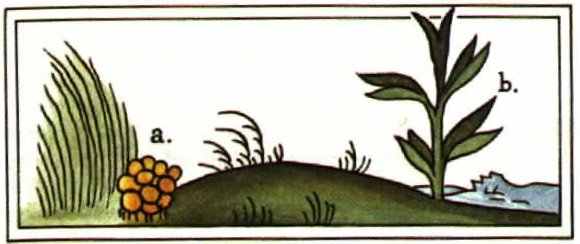

A 16th-century illustration of teononacatl (a), the intoxicating mushroom of the Aztecs, still valued in Mexican magico-religious rites; identity of (b) is unknown. From Sahagun's Historia general de las cosas de Nueva Espana, Val. IV (Florentine Codex).

The all-night Mazatec ceremony, led usually by a woman shaman (curandera), comprises long, complicated, and curiously repetitious chants, percussive beats, and prayers. Often a curing rite takes place during which the practitioner, through the "power" of the sacred mushrooms, communicates and intercedes with supernatural forces. There is no question of the vibrant relevance of the mushroom rituals to modern Indian life in southern Mexico. None of the attraction of these divine mushrooms has been lost as a result of contact with Christianity or modern ideas. The spirit of reverence characteristic of the mushroom ceremony is as profound as that of any of the world's great religions.Curandera with Mazatec patient and dish of sacred mushrooms. Scene is typical of the all-night mushroom ceremony. Curandera is under the influence of the mushrooms.

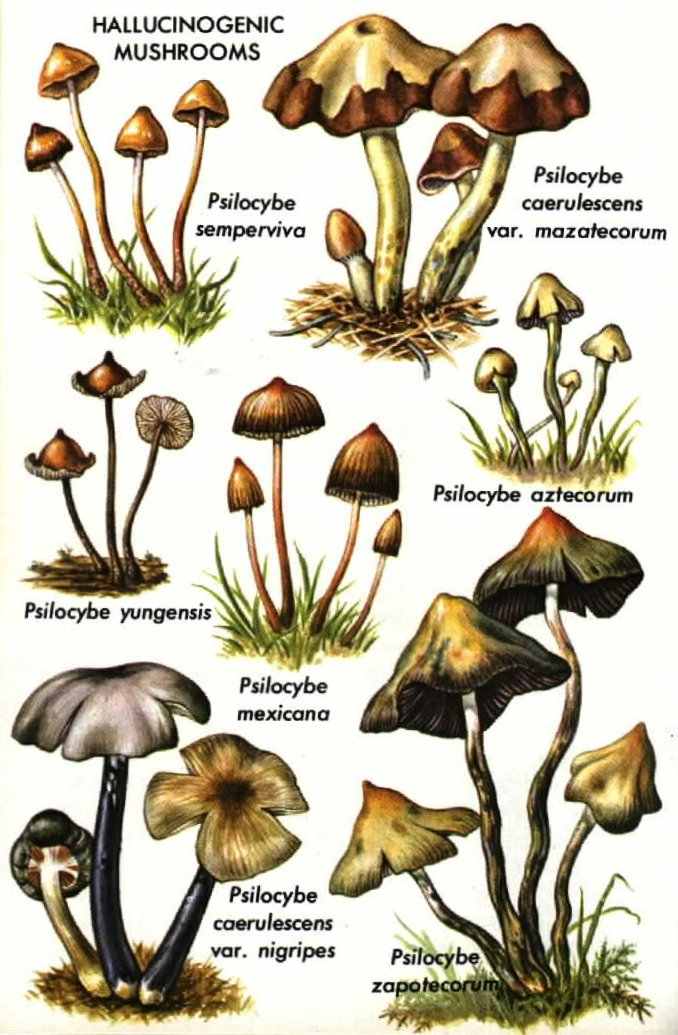

KINDS OF MUSHROOMS USED by different shamans are determined partly by personal preference and partly by the purpose of the use. Seasonal und regional availability also have a bearing on the choice. Stropharia cubensis and Psilocybe mexicana may be the most commonly employed, but half a dozen other species of Psilocybe as well as Conocybe siliginoides and Panaeolus sphinctrinus are also important. The native names are colorful and sometimes significant.. Psilocybe aztecorum is called "children of the waters"; P. zapotecorum, "crown-of-thorns mushroom"; and P. caerulescens var. nigripes, "mushroom of superior reason." (See illustrations on pp. 66-67). The possibility exists that other hallucinogenic species of mushrooms are also used.

It is possible, too, that Psilocybe species are used as inebriants outside of Mexico. P. yungensis has been suggested as the mysterious "tree mushroom" that early Jesuit missionaries reported as being employed by the Yurimagua Indians of Amazonian Peru as the source of a potent intoxicating beverage. This species is known to contain an hallucinogenic principle. Field work in modern times, however, has not disclosed the narcotic use of any mushrooms in the Amazon area.

THE EFFECTS OF THE MUSHROOMS include muscular relaxation or limpness, pupil enlargement, hilarity, and difficulty in concentration. The mushrooms cause both visual and auditory hallucinations. Visions are breathtakingly lifelike, in color, and in constant motion. They are followed by lassitude, mental and physical depression, and alteration of time and spoce perception. The user seems to be isolated from the world around him; without loss of consciousness, he becomes wholly indifferent to his surroundings, and his dreamlike state becomes reality to him. This peculiarity of the intoxication makes it interesting to psychiatrists.

One investigator who ate mushrooms in a Mexican Indian ceremony wrote that "your body lies in the darkness, heavy as lead, but your spirit seems to soar . . . and with the speed of thought to travel where it listeth, in time and space, accompanied by the shaman's singing . . . What you are seeing and . . . hearing appear as one; the music assumes harmonious shapes, giving visual form to its harmonies, and what you are seeing takes on the modalities of music—the music of the spheres.

"All your senses are similarly affected; the cigarette . . . smells as no cigarette before had ever smelled; the glass of simple water is infinitely better than champagne . . . the bemushroomed person is poised in space, a disembodied eye, invisible, incorporeal, seeing but not seen . . . he is the five senses disembodied . . . your soul is free, loses all sense of time, alert as it never was before, living an eternity in a night, seeing infinity in a grain of sand . . . (The visions may be of) almost anything . . . except the scenes of your everyday life." As with other hallucinogens, the effects of the mushrooms may vary with mood and setting.

A scientist's description of his experience after eating 32 dried specimens of Psilocybe mexicana was as follows: ". . . When the doctor supervising the experiment bent over me . . . he was transformed into an Aztec priest, and I would not have been astonished if he had drawn an obsidian knife . . . it amused me to see how the Germanic face . . . had acquired a purely Indian expression. At the peak of the intoxication . . . the rush of interior pictures, mostly abstract motifs rapidly changing in shape and color, reached such an alarming degree that I feared that I would be torn into this whirlpool of form and color and would dissolve. After about six hours, the dream came to an end . . . I felt my return to everyday reality to be a happy return from a strange, fantastic but quite really experienced world into an old and familiar home."

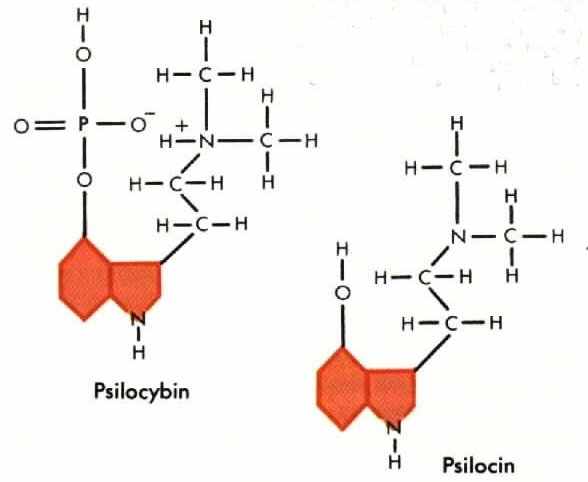

CHEMICAL CONSTITUTION of the hallucinogenic mushrooms has surprised scientists. A white crystalline tryptamine of unusual structure - an acidic phosphoric acid ester of 4-hydroxydimethyltryptamine - was isolated. This indole derivative, named psilocybin, is a new type of structure, a 4-substituted tryptamine with a phosphoric acid radical, a type never before known as a naturally occurring constituent of plant tissue. Some of the mushrooms also contain minute amounts of another indolic compound - psilocin - which is unstable. While psilocybin has been found also in European and North American mushrooms, apparently only in Mexico and Guatemala have psilocybin - containing mushrooms been purposefully used for ceremonial intoxication.

Psilocin is believed by some biochemists to be the precursor

of the more stable psilocybin.

Contents Next