.

Contents...1-10...11-20...21-30...31-40...41-50...51-60...61-70...71-80...81-90

91-100...101-110...111-120...121-130...131-140...141-150...151-156...Index

South American Indians of the upper Orinoco region in characteristic gesticulating postures while under the influence of yopo snuff.

VILCA and SEBIL are snuffs believed to have been prepared in the past from the beans of Anadenanthera colubrina and its variety cébil in central and southern South America, where A. peregrine does not occur. A. colubrina seeds are known to possess the same hallucinogenic principles as A. peregrina (see p. 86).

An early Peruvian report, dated about 1571, states that Inca medicine men foretold the future by communicating with the devil through the use of vilca, or huilca. In Argentina, the early Spaniards found the Comechin Indians taking sebil "through the nose" to become intoxicated, and in another tribe the same plant was chewed for endurance. Since these Indian cultures have disappeared, our knowledge of vilca snuffs and their use is limited.

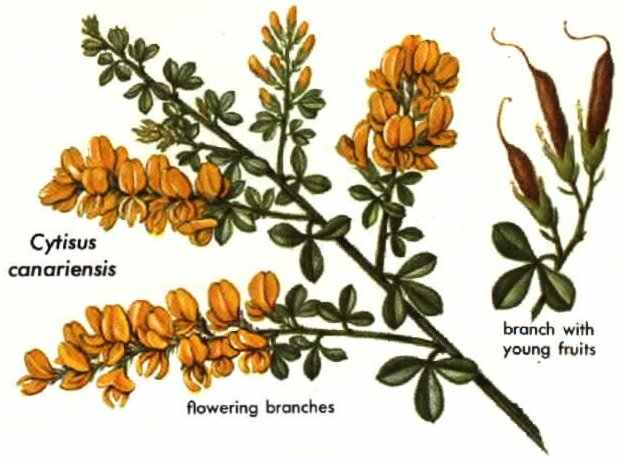

GENISTA (Cytisus canariensis) is employed as an hallucinogen in the magic practices of Yaqui medicine men in northern Mexico. Native to the Canary Islands, the plant was introduced into Mexico. Rarely does any nonindigenous plant find its way into the religious and magic customs of a people. Known also by the scientific name Genista canariensis, this species is the "genista" of florists.

Plants of the genus Cytisus are rich in cytisine, an alkaloid of the lupine group. The alkaloid has never been pharmacologically demonstrated to have hallucinogenic activity, but it is known to be toxic and to cause nausea, convulsions, and death through failure of respiration.

About 80 species of Cytisus, belonging to the bean family, Leguminosae, are known in the Atlantic islands, Europe, and the Mediterranean area. Some species are highly ornamental; some are poisonous.

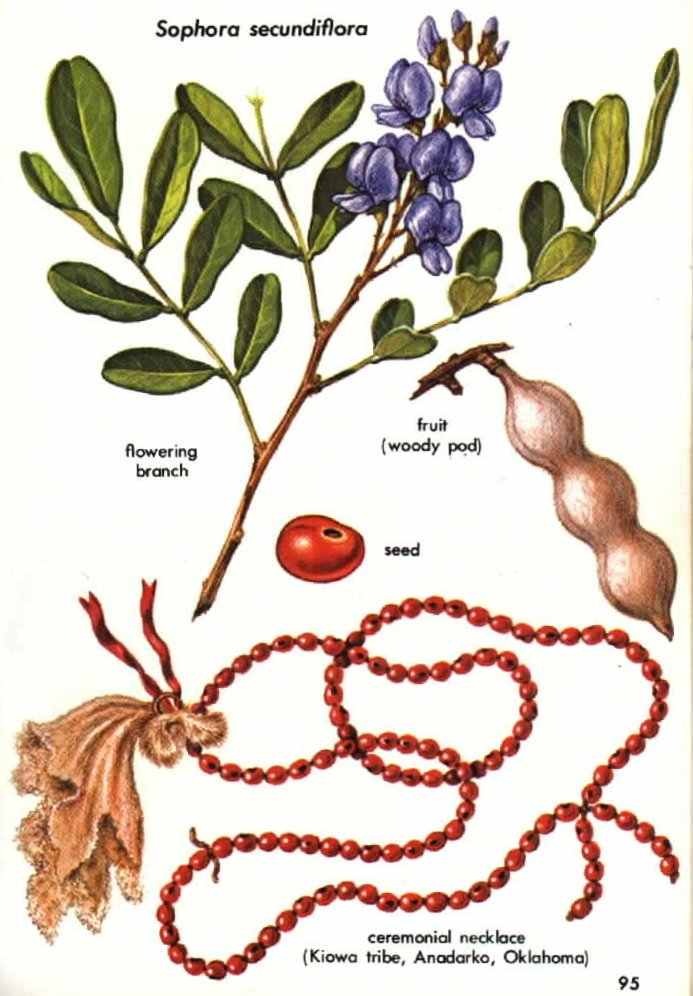

MESCAL BEAN (Saphora secundiflora), also called red bean or coralillo, is a shrub or small tree with silvery pods containing up to six or seven red beans or seeds. Before the peyote religion spread north of the Rio Grande, at least 12 tribes of Indians in northern Mexico, New Mexico, and Texas practiced the vision-seeking Red Bean Dance centered around the ingestion of a drink prepared from these seeds. Known also as the Wichita, Deer, or Whistle Dance, the ceremony utilized the beans as an oracular, divinatory, and hollucinogenic medium.

Because the red bean drink was highly toxic, often resulting in death from overdoses, the arrival of a more spectacular and safer hallucinogen in the form of the peyote cactus (see p. 11 4) led the natives to abandon the Red Bean Dance. Sacred elements do not often disappear completely from a culture; today the seeds are used as an adornment on the uniform of the leader of the peyote ceremony.

An early Spanish explorer mentioned mescal beans as an article of trade in Texas in 1539. Mescal beans have been found at sites dating before A.D. 1000, with one site dating bock to 1500 B.C. Archaeological evidence thus points to the existence of a prehistoric cult or ceremony that used the red beans.

The alkaloid cytisine is present in the beans. It causes nausea, convulsions, and death from asphyxiation through its depressive action on the diaphragm.

The mescal bean is a member of the bean family, Leguminosae. Sophora comprises about 50 species that are native to tropical and warm parts of both hemispheres. One species, S. japonica, is medicinally important as a good source of rutin, used in modern medicine for treating capillary fragility.

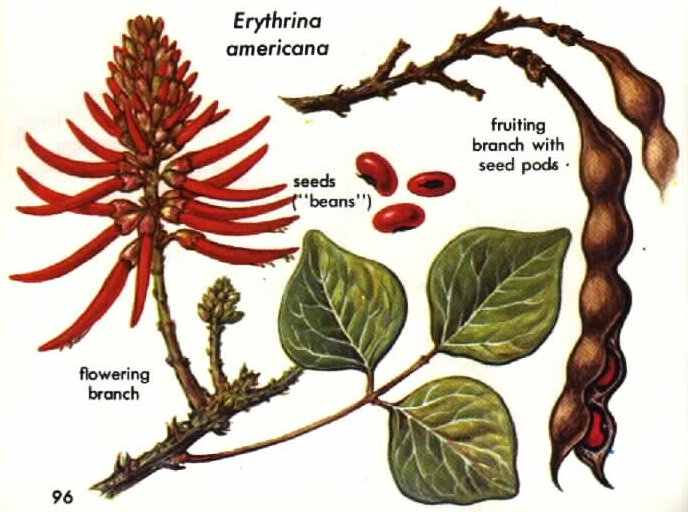

COLORINES (several species of Erythrina) moy be used as hallucinogens in some parts of Mexico. The bright red beans of these plants resemble mescal becans (see p. 94), long used as a narcotic in northern Mexico and in the American Southwest. Both beans are sometimes sold mixed together in herb markets, and the mescal bean plant is sometimes called by the same common name, colorin.

Some species of Erythrina contain alkaloids of the isoquinoline type, which elicit activity resembling that of curare or arrow poisons, but no alkaloids known to possess hallucinogenic properties have yet been found in these seeds.

Some 50 species of Erythrina, members of the bean family, Leguminasce, grow in the tropics and subtropics of both hemispheres.

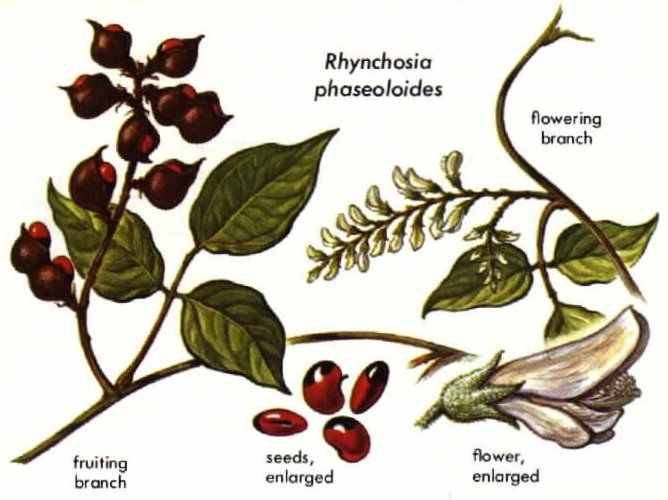

PIULE (several species of Rhynchosia) have beautiful red and black seeds that may have been valued as a narcotic by ancient Mexicans. What appear to be these seeds have been pictured, together with mushrooms, falling from the hand of the Aztec rain god in the Tepantitla fresco of A.D. 300-400 (see p. 59), suggesting hallucinogenic use. Modern Indians in southern Mexico refer to them as piule, one of the names also applied to the hallucinogenic morning-glory seeds.

Seeds of some species of Rhynchosia have given positive alkaloid tests, but the toxic principles hove still not been characterized.

Some 300 species of Rhynchosia, belonging to the bean family, Leguminosae, are known from the tropics and subtropics. The seeds of some species are important in folk medicine in several countries.

AYAHUASCA and CAAPI are two of many local names for either of two species of a South American vine: Banisteriopsis caapi or B. inebrians. Both are gigantic jungle lionas with tiny pink flowers. Like the approximately 100 other species in the genus, their botany is poorly understood. They belong to the family Malpighiaceae.

An hallucinogenic drink made from the bark of these vines is widely used by Indians in the western AmazonóBrazil, Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia. Other local names for the vines or the drink made from them are dopa, natema, pinde, and yaje. The drink is intensely bitter and nauseating.

In Peru and Ecuador, the drink is made by rasping the bark and boiling it. In Colombia and Brazil, the scraped bark is squeezed in cold water to make the drink. Some tribes add other plants to alter or to increase the potency of the drink. In some parts of the Orinoco, the bark is simply chewed. Recent evidence suggests that in the northwestern Amazon the plants may be used in the form of snuff. Ayahuasca is popular for its "telepathic properties," for which, of course, there is no scientific basis.

EARLIEST PUBLISHED REPORTS of ayahuasca date from 1858 but in 1851 Richard Spruce, an English explorer, had discovered the plant from which the intoxicating drink was made and described it as a new species. Spruce also reported that the Guahibos along the Orinoco River in Venezuela chewed the dried stem for its effects instead of preparing a drink from the bark. Spruce collected flowering material and also stems for chemical study. Interestingly, these stems were not analyzed until 1969, but even after more than a century, they gave results (p. 103) indicating the presence of alkaloids.

In the years since Spruce's discovery, many explorers and travelers who passed through the western Amazon region wrote about the drug. It is widely known in the Amazon but the whole story of this plant is yet to be unraveled. Some writers have even confused ayahuasca with completely different narcotic plants.