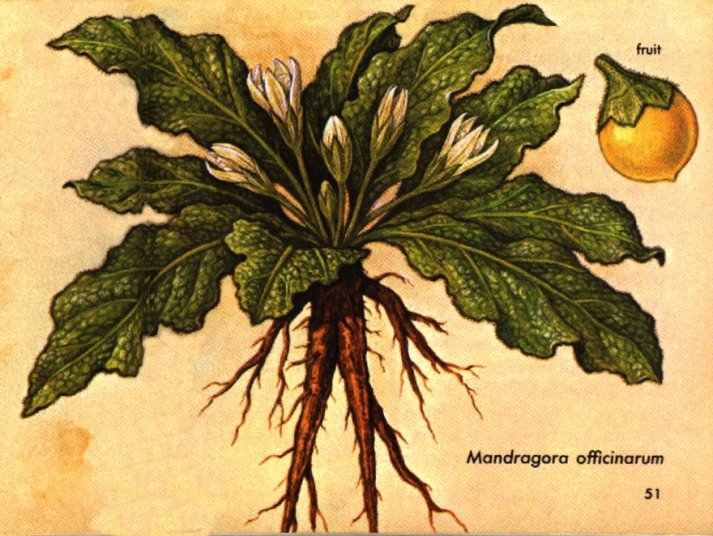

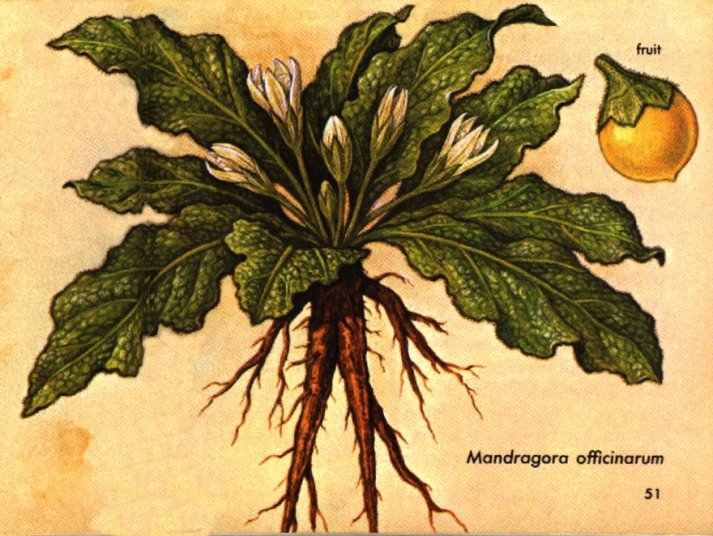

Mandrake, with the Propane alkaloids hyoscyamine, scopolamine, and others, was an active hallucinogenic ingredient of many of the witches' brews of Europe. In fact, it was undoubtedly one of the most potent ingredients in those complex preparations. Mandrake and five other species of Mandragora belong to the nightshade family, Solanaceae, and are native to the area between the Mediterranean and the Himalayas.

DHATURA and DUTRA (Datura metel) are the common names in India for an important Old World species of Datura. The narcotic properties of this purple-flowered member of the deadly nightshade family, Solanaceae, have been known and valued in India since prehistory. The plant has a long history in other countries as well. Some writers have credited it with being responsible for the intoxicating smoke associated with the Oracle of Delphi. Early Chinese writings report an hallucinogen that has been identified with this species. And it is undoubtedly the plant that Avicenna, the Arabian physician, mentioned under the name jouzmathel in the 11th century. Its use as an aphrodisiac in the East Indies was recorded in 1578. The plant was held sacred in China, where people believed that when Buddha preached, heaven sprinkled the plant with dew.

Nevertheless, the utilization of Datura preparations in Asia entailed much less ritual than in the New World. In many parts of Asia, even today, seeds of Datura are often mixed with food and tobacco for illicit use, especially by thieves for stupefying victims, who may remain seriously intoxicated for several days.

Datura metel is commonly mixed with cannabis and smoked in Asia to this day. Leaves of a white-flowered form of the plant (considered by some botanists to be a distinct species, D. fastuosa) are smoked with cannabis or tobacco in many parts of Africa and Asia.

The plant contains highly toxic alkaloids, the principal one being scopolamine. This hallucinogen is present in heaviest concentrations in the leaves and seeds. Scopolamine is found also in the New World species of Datura (pp. 142-147). Datura ferox, a related Old World species, not so widespread in Asia, is also valued for its narcotic and medicinal properties.

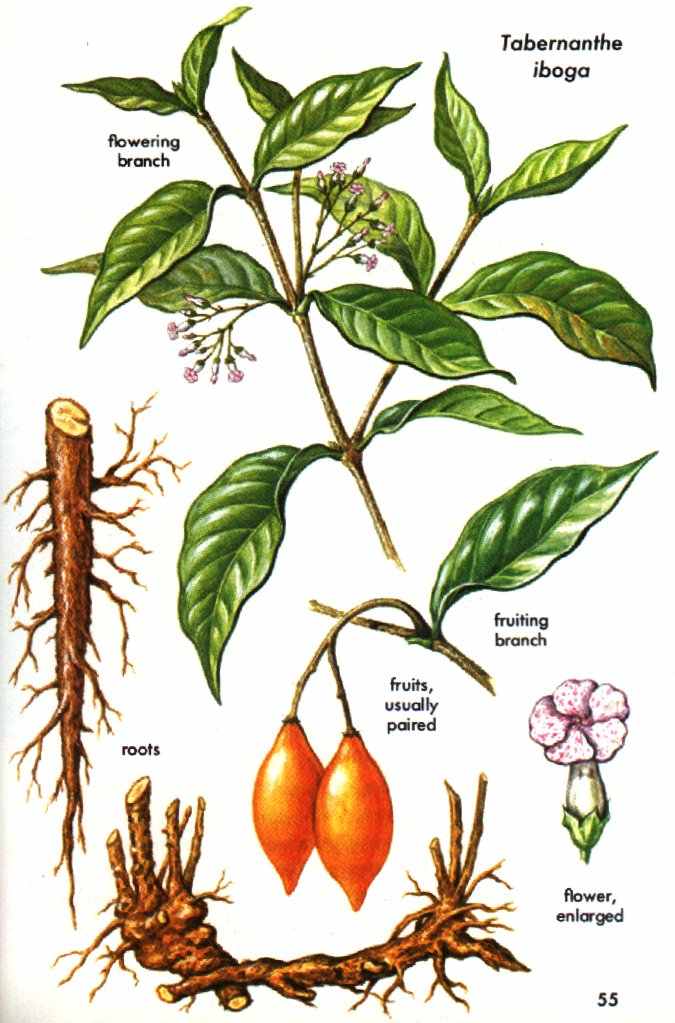

IBOGA (Tabernanthe iboga), native to Gabon and the Congo, is the only member of the dogbane fancily, Apocynaceae, known to be used as an hallucinogen. The plant is of growing importance, providing the strongest single force against the spread of Christianity and Islam in this region.

The yellowish root of the iboga plant is employed in the initiation rites of a number of secret societies, the most famous being the Bwiti cult. Entrance into the cult is conditional on having "seen" the god plant Bwiti, which is accomplished through the use of iboga.The drug, discovered by Europeans toward the middle of the last century, has a reputation as a powerful stimulant and aphrodisiac. Hunters use it to keep themselves awake all night. Large doses induce unworldly visions, and "sorcerers" open take the drug to seek information from ancestors and the spirit world.Ibogaine is the principal indole alkaloid among a dozen others found in iboga. The pharmacology of ibogaine is well known. In addition to being an hallucinogen, ibogoine in large doses is a strong central nervous system stimulant, leading to convulsions, paralysis, and arrest of respiration.

"Payment of the Ancestors," taking place between two shrubby bushes of tabernanthe iboga in the Fang Cult of Bwiti, Congo. (Photo by J. W. Fernandez )

In the New World—North, Central, and South America and the West Indies—the number and cultural importance of hallucinogens reached amazing heights in the past—and in places their role is undiminished.

More than ninety species are employed for their intoxicating principles, compared to fewer than a dozen in the Old World. It would not be an exaggeration to say that some of the New World cultures, particularly in Mexico and South America, were practically enslaved by the religious use of hallucinogens, which acquired a deep and controlling significance in almost every aspect of life. Cultures in North America and the West Indies used fewer hallucinogens, and their role often seemed secondary. Although tobacco and coca, the source of cocaine, have become of worldwide importance, none of the true hallucinogens of the Western Hemisphere has assumed the global significance of the Old World cannabis.

No ethnological study of American Indians can be considered complete without an in-depth appreciation of their hallucinogens. Unexpected discoveries have come from studying the hallucinogenic use of New World plants. Many hallucinogenic preparations called for the addition of plant additives capable of altering the intoxication. The accomplishments of aboriginal Americans in the use of mixtures have been extraordinary.

While known New World hallucinogens are numerous, studies are still uncovering species new to the list. The most curious aspect of the studies, however, is why, in view of their vital importance to New World cultures, the botanical identities of many of the hallucinogens remained unknown until comparatively recent times.

PUFFBALLS (Lycoperdon mixtecorum and L. marginotum) are used by the Mixtec Indicins Of Oaxaca, Mexico as auditory hallucinogens. After eating these fungi, a native hears voices and echoes. There is apparently no ceremony connected with puffballs, and they do not enjoy the place as divinatory agents that the mushrooms do in Oaxaca. L. mixtecorum is the stronger of the two. It is called gi-i-wa, meaning ''fungus of the first quality." L. marginatum, which has a strong odor of excrement is known as gi-i-sa-wa, meaning ''fungus of the second quality.

Although intoxicating substances have not yet been found in the puffballs, there are reports in the literature that some of them have had narcotic effects when eaten. Most of the estimated 50 to 100 species of Lycoperdon grow in mossy forests of the temperate zone. They belong to the Lycoperdaceae, a family of the Gasteromycetes.

The use of hallucinogenic mushrooms, which dates back several thousand years, centers in the mountains of southern Mexico.

MUSHROOMS of many species were used as hallucinogens by the Aztec Indians, who colled them teonanacotl, meaning "flesh of the gods" in the Nahuatl Indian language. These mushrooms, all of the family Agaricaceae, are still valued in Mexican magic or eligious rites. They belong to four genera: Conocybe and Panaeolus, almost cosmopolitan in their range; Psilocybe, found in North and South America, Europe, and Asia; and Stropharia, known in North America, the West Indies, and Europe.

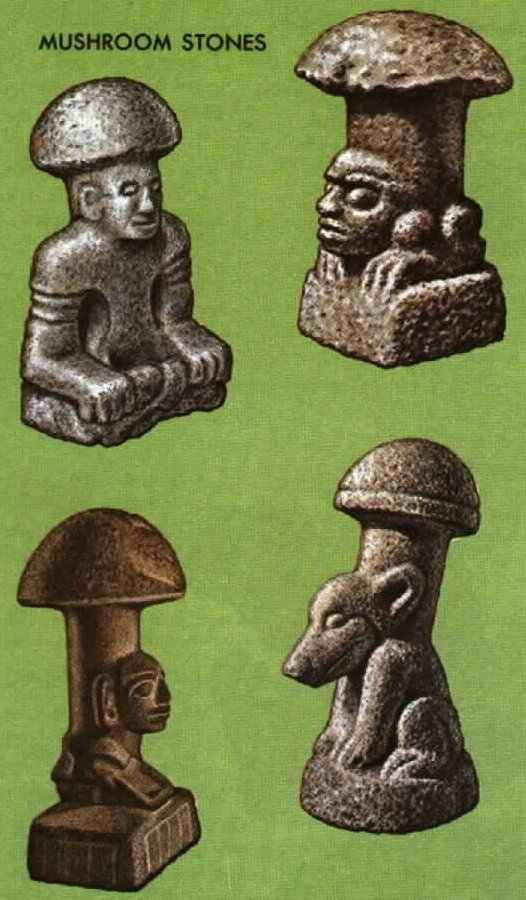

MUSHROOM WORSHIP seems to have roots in centuries of native tradition. Mexican frescoes, going back to A.D. 300, have designs suggestive of mushrooms. Even more remarkable are the artifacts called mushroom stones (p. 60), excavated in large numbers from highland Maya sites in Guatemala and dating buck to 1000 B.C. Consisting of a stem with a human or animal foce and surmounted by an umbrella-shaped top, they long puzzled archaeologists. Now interpreted as a kind of icon connected with religious rituals, they indicate that 3,000 years ago, a sophisticatedreligion surrounded the sacramental use of these fungi.

It has been suggested that perhaps mushrooms were the earliest hallucinogenic plants to be discovered. The other- worldly experience induced by these mysterious forms of plant life could easily have suggested a spiritual plane of existence.Detail from a fresco at a Tepantitla (Teotihuacán Mexico) representing Tloloc, the god of clouds, rain, and waters. Note the pale blue mushrooms with orange stems and also the "colorines' - the darker blue, bean-shaped forms with red spots. See pages 90 and 97 for discussion of colorines and piule. (After Heim and Wasson.)